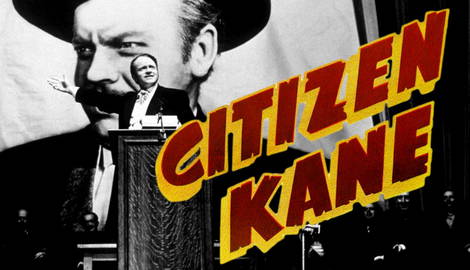

Not only does Citizen Kane remain a miracle of modernist cinema, but the fact that it was made during the height of Hollywood studio control also renders it unparalleled among the weightiest and most influential milestones of feature filmmaking. The film launched the meteoric screen career of the then-25-year-old Orson Welles. Here’s everything you need to know about why Citizen Kane is still the greatest movie of all time.

Who Was Orson Welles, The Man Behind Citizen Kane?

Orson Welles was the enfant terrible of radio and the New York stage who had panicked America with his Mercury Theatre’s notorious 1938 broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. It was the subject of one of Hollywood’s most pitched censorship struggles, pitting the powerful newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst against RKO, a minor member of the classic studio majors.

But for newer generations, Welles’ prodigious 1941 directorial debut may not carry the weight of its reputation well, not unlike Welles himself (1915-1985) who in his later years rather infamously ballooned in size (amply illustrated in his TV adverts and on talk shows), light years from the dashing figure he cut in his heady days as the wunderkind toast of both coasts. The film’s reputation has also taken knocks of late from critical circles. Each decade from 1962 until 2002, the British Film Institute’s Sight and Sound magazine voted it the greatest of all time, an astounding record not broken until 2012 when Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo toppled it. To add insult to injury Kane was downgraded to third-place BFI citizenship in 2022 when Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975) vaulted from feminist left field to take first prize.

What Makes the Movie So Compelling?

Let’s start with flashbacks. Welles and his co-writer Herman Mankiewicz (a pairing that has been the subject of at least one controversial book and the 2020 Netflix film Mank) construct their story around a series of flashbacks that ensue after the opening exit of its protagonist Charles Foster Kane, once a media mogul and now an aged recluse in his decaying Florida palace. What was the last word he whispered and what did it mean? Is this the ultimate piece of a jigsaw puzzle that will unlock the secrets of his life?

While Welles and Mankiewicz hardly invented the flashback what is unique are the multiple characters who tell them, including one whose memory is relayed in the form of a diary chapter, all prompted by questions from a dogged reporter. So while the film begins in the present, much of it consists of previous events presented out of chronological order. The very effect of starting with the demise of the main character—a framing device that allows no real escape or Hollywood ending—would be essential to the doomed world of American film noir of the later 1940s.

Back in the days not long ago when feature films were filmed on reels of 35mm film (recording images at 24 frames per second), there were many U.S. cinematographers who shined, but the brightest might have been Gregg Toland, who alas died young at the age of 44 in 1948. Among other techniques, he was a master of what’s called photography in depth or deep focus. In classic Hollywood before high-speed black-and-white or color film stock, it was difficult if not impossible to keep both the foreground and background of a shot in focus, especially indoors or under low light conditions.

Utilizing faster lenses and more intense light (and, sometimes, trick photography) Toland was able to give Welles realistic, expansive, yet nuanced compositions that negated the need to cut between objects within a scene. Thus, in a textbook example from Kane’s stunted childhood, young Charles is playing in the snow outside his family’s Colorado cabin while inside his parents are about to hand him (and his happenstance fortune) over to his Dickensian new guardian. In a long mobile camera shot lasting almost two minutes and cued by the diary flashback, we first see Charlie at a distance through what’s revealed to be an open window as his mother speaks of his departure; then we see her retreat to a table where she signs him away, during which time her husband closes the window, leaving Charles framed far in the background; and then we see her return to the window to reopen it, ending with a cut to a close-up of her wistfully gazing off at Charlie. Pregnant with oedipal baggage, Toland’s bravura long take traces of Charlie’s forceful, if not traumatic, ejection from his mother, a defining moment rendered even more poignant by his ironic playful taunt, “… the Union forever!”

Inspired by the stylized naturalism of deep focus, Kane swells into a watershed for important critics such as France’s André Bazin, who championed it as a trailblazer in world cinema’s post-World War II transformation away from artifice into realistic documentary-like modes, a movement that encompasses classics from the Italian neo-realist Bicycle Thieves (1948) to Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront (1954). Yet at the same time, in the same film, Welles and his editor—and future director—Robert Wise brilliantly take a formalist tack, utilizing a cinematic montage that brutally boils down Kane’s first marriage into six whirlwind snapshots over time, all at the breakfast table. Cued by voice-over narration, this flashback opens on the couple’s honeymoon ardor but closes with a serving of chilly silence, accented visually by the couple’s growing distance from each other and the lengthening of the table.

The Sound of Citizen Kane

From that opening deathbed exclamation, Welles and his sound crew deftly crafted the audio track to simulate a sense of depth for both the dialogue and a scene’s ambient noises. In this way, Welles does for his soundtrack what deep focus does for his visuals—creating a fuller, richer aural dimension, a penchant for reflecting his virtuoso talents in both theater and radio. No discussion of sound in Kane would be complete without giving a shout-out to another irreplaceable cog, composer Bernard Herrmann, who would go on to a prolific Hollywood career, writing marvelously expressive orchestral scores for Alfred Hitchcock classics (including Psycho and Vertigo) and, in his valedictory triumph, Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver.

Herrmann excelled at fashioning Wagnerian musical leitmotifs, that is, unique melodies that are identified with specific characters (think of John Williams’ relentless shark theme in Jaws). It’s noteworthy that Kane’s own Rosebud theme wafts through several scenes, causing attentive audiences to tune in for clues.

The Set

When Welles first took a tour of all the resources at his disposal in the RKO studios, he famously gushed, “This is the biggest electric train set a boy ever had!” Not simply Toland’s cameras and lights, Wise’s editing machines, or Herrmann’s allusive music, but equally the props and sets as overseen by Perry Ferguson, the film’s associate art director. With nearly all the scenes shot in studio soundstages, on less than a $1 million budget Kane was far from the spendthrift production that its detractors called it. Indeed, impressively large-looking sets like the baronial main hall of Kane’s Xanadu mansion were in fact only partially built to save on costs and its incompleteness was cleverly masked by Toland’s gloomy low-key lighting. Combine that with deep focus (via wide-angle lenses that make background objects appear even more distant) and seemingly faraway sounds (enhanced by echoes), and the eye is tricked into perceiving a bigger space than what’s actually there. “Pay no attention to that man behind the curtain,” indeed.

The Legacy of Citizen Kane

While ostensibly the story of the rise and fall of Charles Foster Kane (a tour-de-force acted by young Welles himself), most anyone in 1941 media who read the script or saw the movie would have thought Welles and Mankiewicz’s magnum opus was no doubt a veiled biopic of Hearst, and not just of him but equally of his longtime mistress, actress Marion Davies. Instead of boosting the screen career of his mistress, as Hearst did, Kane pushes Susan Alexander (Dorothy Comingore) into singing grand opera, much against her will—and nearly into suicide. Evidently, it was the portrayal of Alexander/Davies as a boozy, no-talent chanteuse that got Hearst to stop the presses and call out the hounds on RKO and Welles. It didn’t help matters that Welles was not just a brash wunderkind but came from the highfalutin New York theater world. He was also a Roosevelt New Dealer in politically conservative Hollywood, plus he wore a beard.

Over 80 years later, when all the principal players have bowed out and Hearst only lives on through his namesake media empire and via tours of his legendary San Simeon California castle (once the site of Hollywood’s most exclusive sleepover parties), Citizen Kane has a new resonance, not simply for its remarkable technical, writing, and acting achievements, but for its timeless themes and discourses on moneyed U.S. society, the press, and the individual. It’s the story of mass-media power, of course, centered on one man whose reckless and materialistic egotism tramples his youthful idealism. While it’s a Hearst roman-a-clef, the hero’s tragic trajectory bears an uncanny resemblance to any number of U.S. cultural and entrepreneurial giants—from Howard Hughes to Elvis Presley and beyond—who began their historic careers in fame, fast company, and fortune yet ended them as sad, solitary wrecks.

Here too, as Kane’s career unfolds as a publisher, he is in the jovial company of his two closest friends, Jed (Joseph Cotten) and Mr. Bernstein (Everett Sloane), who both truly care for him. There are hints that Jed may be gay. By the end—that is, the beginning and middle—of the film, all three appear aged and estranged, and their friendships faded like yesterday’s news.

Perhaps even more timely, Kane literally lords over his paramour-turned-wife Susan, controlling her—and others—not just with wealth and the printed word but with his very voice, which we hear amplified through microphones or simply through his own vocal power. We can readily deem such artistic continuities as belonging to an auteur, that widely overused descriptor of a director whose distinctive themes and/or techniques appear from work to work, if often subtle or covert. Despite the successive waves of feminism from the years of suffragettes to Women’s Liberation and MeToo, were we listening we would have heard the voices of females used and abused—sexually and otherwise—by domineering men. Perhaps even more so now since women have fully entered the workplace in the West, including in fields where angels once feared to tread.

Citizen Kane has all this to say and much more. The eminent New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael grudgingly called it a shallow masterpiece (while also controversially downplaying Welles’ contribution to the script). Certainly, it is no warm and fuzzy Hollywood rom-com, and nor is it the hot-blooded New Hollywood epic masterpiece that is The Godfather. If you watch Citizen Kane, not once but several times, like with the greatest symphonies, the more you play it, the more you will see and hear.