Claude Cahun is not the most well-known name among surrealist artists. This is remarkable because her non-binary perspective gives an original take on surrealism. Cahun was ahead of her time, and this unique identity directly influenced her artwork. She used elements of mirrors, collages, and doubling in her work to reflect diverging from social norms. At the time, she did not receive recognition. Her work only came to light again in the 1990s.

Below, we’ll take a look at her life: from early identity to later activism.

Claude Cahun’s Early Life

Claude Cahun was born as Lucy Renee Mathilde Schwob on October 25, 1894. She was from Nantes, France, and was born to a provincial but intellectual Jewish family.

Marcel Schwob, the French symbolist-writer, was Cahun’s uncle. Another notable writer and Orientalist, David Léon Cahun, was her great uncle.

From an early age, Cahun grappled with her gender identity. By the early 1920s, she adopted the name Claude because it could be a man’s or a woman’s.

Her last, name Cahun, was taken from her grandmother, Mathilda. Cahun’s mother, Mary-Antoinette Courbebaisse, suffered from severe mental illness. She was ultimately sent to a permanent psychiatric facility, making Mathilda Cahun’s primary caretaker.

When Cahun was about 15 years old, she met Suzanne Malherbe (later Marcel Moore). Her father married Malherbe’s mother in 1917, so the two became step sisters. However, they were also lesbian lovers in privacy.

In 1920, the pair moved to Paris. They lived comfortably with the help of familial finances, and hid their relationship behind the guise of family. In this time, Cahun also studied in the department of Philosophy at the Sorbonne.

Cahun joined the Association des Écrivains et Artistes Révolutionnaires, where she would meet other prominent surrealists. Writer René Crevel and painter Henri Michaux were both known to be in Cahun’s circle. Writer André Breton even commented on Cahun, describing her as “one of the most curious spirits of our time.”

Cahun exhibited surrealism in both writing and art. There wasn’t a lot of appreciation for her work at the time, but we can see the emergence of her main themes in Disavowals (1930).

Disavowals: Cahun’s Enigmatic Memoir

Disavowals (or Cancelled Confessions / Aveux non Avenues) (1930) was an autobiography that featured surrealist photomontages, and aimed to criticize conservatism in France. It featured a collection of poems, dreams, and philosophical dialogues about peculiar identities and uniqueness. Cahun began working on it from 1919 to 1925, adding another section in 1928. This period coincides with when many of her stylized, gender non-confirming photographs were shot.

In it, she made the position on her gender clear, remarking, ” Shuffle the cards. Masculine? Feminine? It depends on the situation. Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.”

The photomontage pictured above makes the cover of Disavowals. Historians have noted that the image of the eye between hands can recall both surrealism and psychoanalysis. Some attribute the position of the hands and the surrounding folds to resemble a phallus or “labial shapes“. Whichever interpretation Cahun intended, the mixed imagery and symbolism fall in line with Disavowal’s theme of searching for oneself.

The opening statement reinforces this atmosphere, which reads:

“The invisible adventure.

The lens tracks the eyes, the mouth, the wrinkles skin deep… the expression on the face is fierce, sometimes tragic. And then calm – a knowing calm, worked on, flashy. A professional smile – and voilà!

The hand-held mirror reappears, and the rouge and the eye shadow. A beat. Full stop.”

Disavowals was not critically well received or popular. Regardless, Cahun continued to visit major artist scenes in Europe.

In 1936, she visited the Surrealist exhibition at the Gallerie Charles Raton, Paris. She also viewed the International Surrealist Exhibition at the New Burlington Galleries in London. However, her photography would not become widely remarked on until many years later.

Notable Photography

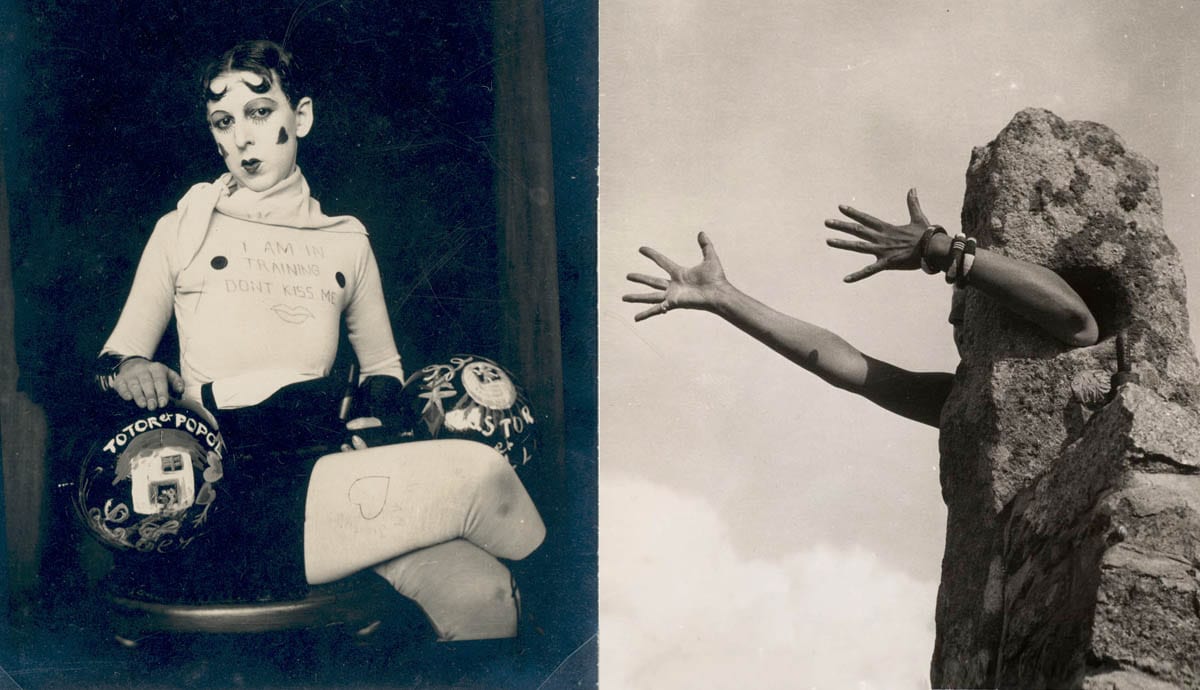

Cahun combined several elements of surrealism, including reflections and doubling. Her partner, Moore, was often the one behind the camera.

A common theme in her work was the subversion of what societal expectations for women. Even in photographs where Cahun appears more traditionally feminine, she adds elements such as cropped hair to challenge beauty expectations.

We can see this in her first major work, Self Portrait as a Young Girl.

Self Portrait as a Young Girl, 1914

Cahun’s hair here is reminiscent of Medusa‘s. Most observers note that the tone and appearance isn’t attractive. Many depictions of women on a bed in fine art are eroticized. Cahun’s take is a stark contrast to that. Many speculate that this was a reflection of her own depression when her mother fell ill.

There’s a cropped version of this photograph that focuses on Cahun’s face. In the book Reading Claude Cahun’s Disavowals, it’s speculated “that the purpose of taking the photograph was, from the start, to create a medusa like image.” Regardless, this marks an early intention to portray complex emotions through unconventional imagery.

Untitled (Self Portrait with Mirror), 1928

This photograph is a highlight in Cahun’s androgynous expression. Instead of looking at her own reflection in vanity, Cahun does not face herself here. The contrast between each angle of her face reveals a different part of her identity. The one watching the viewer is half hidden by the collar, while the mirror reveals a vulnerable, exposed neck.

This might be viewed as an extension of Cahun’s “confessions”, or perhaps as an act of defiance.

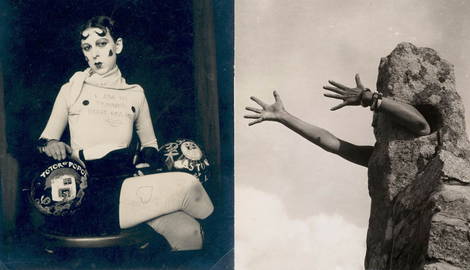

I Am In Training Do Not Kiss Me, 1927

This is one of Cahun’s most defining photographs. Many view this presentation of identity as almost homosexual. It has features that are neither fully masculine nor feminine, and the part at the center of her hair resembles Oscar Wilde’. Historians have remarked that this appearance is more of dandy, but the lipstick and hearts keep it difficult to label.

“Her many female variations make no attempt to seduce. She either parodies flirtatiousness and ridiculously exaggerates the facial makeup of a vamp…”, suggests writer Katy Kline.

Anti-Nazi Resistance

When war tension began to rise in France, Cahun and Moore fled for sanctuary. They settled in the island of Jersey, off the coast of France, to escape growing anti-Semitism. They made her home in St. Brelade, where the islanders came to nickname them “mesdames” (the ladies).

Unfortunately, Cahun and Moore did not completely escape. The Nazis occupied the island in 1940. Thus, the pair decided to resist by spreading discouraging propaganda, disguised as a German soldier.

Moore was fluent in German, so they took news stories from the BBC (via illegal radio) and translated snippets into flyers. They combined handwriting with typing and imagery that described a German victory as a lost cause. They signed off as der Soldat ohne Namen (The Soldier with No Name), and slipped them into cigarette boxes and windshield wipers.

In 1944, les mesdames were convicted of undermining the Germans, and sentenced to death. The Nazis confiscated her property, and destroyed much of her art. They never did execute the pair, and the island was liberated in May, 1945. The two were released, and in 1951, Cahun was awarded the Medal of French Gratitude for her resistance.

Just three years later, she died due to poor health which was worsened by her prison time. Moore continued to live in Jersey, passing away later in 1972.

Claude Cahun’s Legacy in Art and Gender

Cahun’s death didn’t get popular attention or acknowledgement. It was in 1992 that her work gained a surge of appreciation. Francois Leperlier published a book, Cahun: L’ecart et la metamorphose (The Gap and the Metamorphosis), that began to reignite public awareness of Cahun’s work.

The Jersey Heritage Trust, which now holds a large roster of les mesdames’ work, only learned of her when an islander brought them her collection. In 1993, the Jersey Museum held an exhibition, Surrealist Sisters. Her work began to expand to more events, including a 1995 exhibition at Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Cahun’s influence has spread among even popular culture. Paris’ Sixth District includes a street named Allée Claude Cahun et Marcel Moore in her honor. In 2007, singer David Bowie remarked, “You could call her transgressive or you could call her a cross dressing Man Ray with surrealist tendencies.” She has also been an inspiration for contemporary artist Gillian Wearing, who dressed as Cahun with a mask.

Beyond her publications and intellectual musings, Cahun never enforced specific interpretations for her pieces. This has provided historians with an opportunity for diverse discussion and theories. Yet, Cahun’s themes of eroticism, androgyny, and surreal compositions have continued to fascinate LGBT+ and surreal commentators alike.