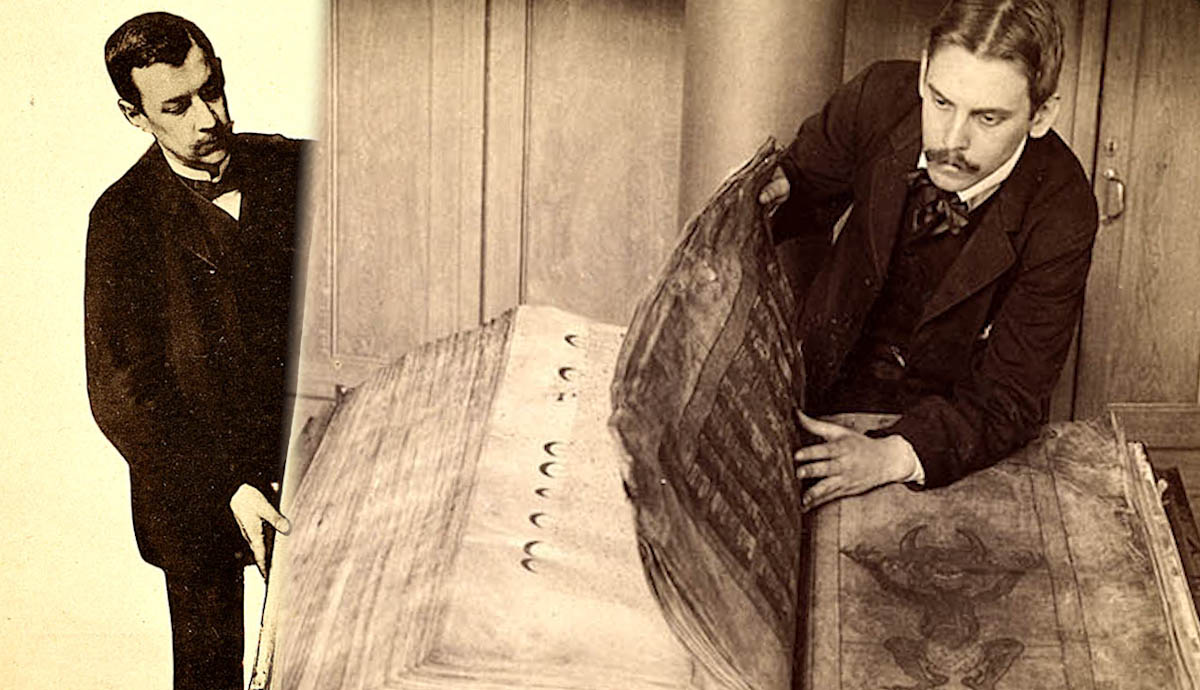

Codex Gigas remains the world’s largest preserved medieval manuscript. In Latin, the name Codex Gigas means “the Giant Book.” It is 36 inches tall, 20 inches wide, nearly 9 inches thick, and weighs around 165 pounds. The impressive binding consists of leather and ornamental metal. Each page shows impeccable precision and relentless attention to detail. This outstanding work includes the entire Latin Bible, Isidore of Seville’s Encyclopaedia Etymologia, Josephus’ Antiquities of the Jews, and Cosmas of Prague’s Chronicle of Bohemia. Additionally, it includes numerous writings describing magic formulae, exorcism rituals, and a calendar. Codex Gigas was supposed to contain all the world’s knowledge among the pages of a single book.

The Devil Is In The Details: The Mastery Behind Codex Gigas

Codex Gigas continues to amaze, with unique colors and flawless details adorning this medieval manuscript. The entirety of the text is strikingly illuminated and embellished. Colorful illustrations, precise borders, and highly stylized letters continuously attract the attention of readers.

Various aspects of the Codex Gigas continue to perplex even the most knowledgeable historians. Experts don’t know the answer to how the book was even composed. This is mostly because of the imbalance between the book’s comprehensive attention to detail and its massive scope. Namely, the general nature of the writing is utterly consistent, with no variations in looks or quality. The experts concluded that this medieval manuscript is the work of a single scribe. Most surprisingly, the continuous uniformity suggests that the creator completed the Codex Gigas in a short period. However, manuscript specialists claim that this was actually impossible to achieve.

Experts state that the Codex Gigas would have taken over five years of constant writing to complete. Realistically, this medieval manuscript would have required more than twenty-five years of work. However, the scribe’s work shows no signs of aging nor a change in skill or style. The creator’s masterful uniformity remains a phenomenon.

This medieval manuscript dates back to the early 13th century, between the walls of the Benedictine monastery of Podlažice in Bohemia. Subsequently, it became part of the imperial library of Rudolf II in Prague. In 1648, during the Thirty Years’ War, the entire royal library collection was taken by the Swedish army. Codex Gigas now resides at its final destination, the National Library of Sweden, located in Stockholm.

The Sins of the Monk: The Curse of the Medieval Manuscript

Returning to the 13th century in Bohemia, a monk named Herman committed an unforgivable abomination. He broke his sacred vows, and therefore, he received a death sentence. The monk was to face immurement, meaning he was to be walled up alive behind the monastery walls. Just before the final brick was put in its place, the monk begged for mercy. The Abbot then offered him a deal. The monk was challenged to create a book that would include all the world’s knowledge, and he was to do it in a single night. As the time passed, the monk Herman had no choice but to bargain with his soul. He gave his soul away in exchange for a completed book. The following morning, the monk presented the Abbot with his work, and his life was spared.

In the Codex Gigas, the scribe’s signature reads Hermanus Inclusus. This detail can either confirm or undermine the previously mentioned legend of the medieval manuscript. Hermanus translates as Herman, which stands for the name of the monk. In Latin, the word Inclusus means either punishment or voluntary isolation. This translation illuminates another possible theory in which the monk dedicated his life to creating a masterpiece.

Namely, multiple details scattered across the medieval manuscript indicate a possible guilty conscience lurking behind the author’s mind. The old medieval belief states that it is possible to atone for your sins by copying holy texts. That belief could support the theory of the monk’s redemption.

A long list of sinful confessions also finds its place among the pages of the manuscript. And, it is placed just before the depiction of heaven. This text differs from the rest of the Codex Gigas. It is written in capital letters. The monk is begging for forgiveness across five entire pages, describing his every sin in detail. The subsequent pages present a full-scale representation of heaven and the devil. This particular sheet makes Codex Gigas the only medieval manuscript with a full-page portrait of the devil himself. The beast is shown in an empty landscape, trapped between two towers.

This creature is staring from the blankness of the page, drawn with red horns and two tongues, wearing nothing but an ermine loincloth. It is interesting to know that ermine was worn only by royalty, so this detail defines the devil as the prince of darkness. This portrait, in particular, is what earned the Codex Gigas yet another title – The Devil’s Bible.

Right by the illustration of the devil is the depiction of heaven, presented through numerous rows of white buildings. Paradise lies between two tall towers. In that way, it is linked to the devil’s portrait. What makes the kingdom of heaven unsettling is the fact that there are no signs of life. Without explanation, the author drew heaven utterly deprived of life.

This double-page spread ominously depicts the very nature of good and evil, standing side by side. These illuminations are also the only full-page drawings in the Codex Gigas.

Pages that follow contain writings describing certain magical spells and demonic conjurations. These particular texts were intended for exorcism rituals. They were meant to repel illnesses and hallucinations.

According to experts, all the writings and artworks inside the Codex Gigas belong to a single man, although it was common practice for scribes to collaborate with multiple illustrators. Despite the author’s undeniable talent, no other works of his have ever been found.

The Ten Missing Pages of the Codex Gigas

Yet another legend haunts the Codex Gigas, and it is known as “The Curse of the Devil’s Bible.” In 1477, the Benedictine monastery in Bohemia, which is known as the origin of the medieval manuscript, struggled financially. Therefore, the monks had no choice but to sell away their most treasured possession, the Codex Gigas. The manuscript was then owned by the Benedictine monastery in Břevnov. Soon afterward, the Bohemia monastery fell under the havoc of the Hussite Revolution.

The medieval manuscript remained in Břevnov until the year 1593; the monastery then decided to lend the book to the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolf II. Sadly, the Codex Gigas never found its way back to the monastery, since the Emperor developed an obsession with the manuscript. Over time, his fascination grew and his reign was affected by his paranoia. It wasn’t long before the Emperor’s family decided to overthrow him from his position. Six years following the Emperor’s death marked the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War. The war ended with the Swedish army taking the Emperor’s library collection, including the Codex Gigas.

In 1697, a wildfire happened in the royal castle of Stockholm. Just moments before the flames reached the royal library, the librarian in chief ordered his men to salvage as many precious works as possible. The men had no choice but to start throwing the books out of the windows. Many people believe that when the 165-pound medieval manuscript flew through the air its ten missing pages got torn out from the binding. Those mysterious pages remain missing until this day. Three days after the incident, there was a trial to uncover the cause of the wildfire. Since the chief fire watcher and his two men weren’t in their right positions, they received a death sentence. However, the exact cause of the wildfire remains a mystery.

However, the original theory explaining the missing pages of the Codex Gigas has its faults. Numerous archivists claim that the missing section didn’t simply fall out but was instead ripped out on purpose. Additionally, many scholars believe that the content of the missing pages includes the rules of the Benedictine monastery in Bohemia.

Due to the considerable size of the pages in the manuscript, it’s safe to say that the monastery rules couldn’t fill the entire ten pages.

Over time, new questions and mysteries arise regarding this medieval manuscript. Codex Gigas, with its ancient secrets and ominous aura, refuses to give away its arcane answers. Instead, it leaves us in a state of constant wonder, offering infinite enigmas that may never be resolved.