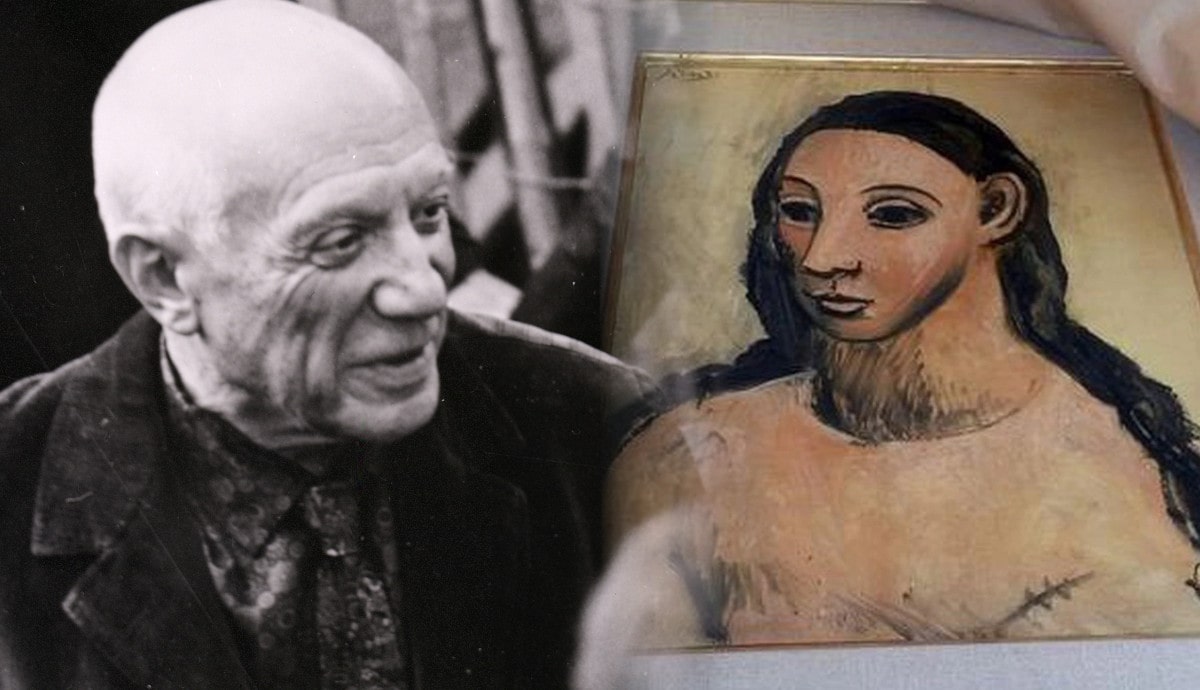

Spanish billionaire Jaime Botin of the Santander banking dynasty was sentenced to 18 months in prison and fined €52.4 million ($58 million) for smuggling a Picasso painting, Head of a Young Woman from 1906 out of Spain.

A Picasso Painting Found on a Yacht

The stolen Picasso painting was found on Botin’s yacht called Adix off the coast of Corsica, France over four years ago in 2015 and he was recently sentenced for the crime in January 2020. Apparently, Botin plans to appeal the verdict stating “defects and errors” in the ruling.

The Spanish Ministry of Culture designated Head of a Young Woman as a non-exportable good in 2013 and that same year, Christie’s London hoped to sell the piece at one of their auctions. Spain wouldn’t allow it. Additionally, in 2015, Botin’s late brother Emilio was also prohibited from moving the painting.

Spain has some of the strictest heritage laws in Europe and Botin’s conviction makes this clear. Permits are required when attempting to export “national treasures” which include any Spanish work over 100 years old. Picasso’s Head of a Young Woman falls into this category.

Throughout the trial and accusations, Botin has repeatedly asserted that he never intended to sell the piece as his prosecutors claim. However, the prosecution states that he was on his way to London hoping to sell the Picasso at an auction house.

On the contrary, Botin said he was on his way to Switzerland to store the painting for safekeeping.

Botin bought Head of a Young Woman in 1977 in London at the Marlborough Fine Art Fair and he claimed that Spain has no jurisdiction over the work of art. One of his arguments in court was that he kept the painting on his yacht the entire time he owned it, meaning it was never actually in Spain.

The validity of these claims, however, is unverified. Still, Botin told the New York Times in October 2015, “This is my painting. This is not a painting of Spain. This is not a national treasure, and I can do what I want with this painting.”

While Botin was on trial, the painting was kept at the Reina Sofia Museum and although the public institution is autonomous, it relies heavily on the Spanish Ministry of Culture and therefore, it is part of the state.

According to a Times report, in addition to filing an appeal, Botin allegedly met with the former Spanish culture minister Jose Guirao to potentially strike a deal where the businessman would receive a lesser sentence if he relinquishes ownership of Head of a Young Woman to the state.

About the Painting

Head of a Young Woman is a rare portrait of a wide-eyed woman and was created during Picasso’s rose period. As historians and followers of Picasso’s career, his art fell into distinct periods which are, for the most part, starkly different from one another.

These days, many people think of Picasso as the face of cubism – which indeed he is. But, he also created pieces like this that are less abstract. Although, his personal style does seem to bleed through even in this portrait.

Head of a Young Woman is valued at $31 million.

What the Verdict Means for Art

Botin’s fight for what he deems as his personal property brings up a valid concern. With the booming art market and international borders becoming less and less clear, how should art collectors and nations come to terms with private property versus national treasures?

In this case, Madrid’s interests outweighed the interests of a private citizen. But lawyers argue that declaring an item as a national treasure destroys its market value.

And beyond that, what makes something a national treasure? What are the qualifications? As with most things in the world of art, determining these values is often subjective.

However, Botin didn’t do himself any favors in this instance. Less than six months before the seizure of the smuggled painting, Spain barred him from moving it when he was denied the appropriate permit.

So, according to Bloomberg, Botin instructed the captain of his yacht to lie to law enforcement (which he did when he failed to list the portrait as one of the works of art onboard) and based on some of his other actions, such as having Christie’s apply for a permit to sell the portrait, Botin became an untrustworthy suspect.

Overall, even if Botin has a valid point that claiming something as a national treasure imposes on the owner’s rights to their private property, surely, you shouldn’t then break the law in order to have things your way. Is there a way to resolve this? Still, you can probably understand Botin’s frustration.

Since the news is still breaking and it’s unclear whether Botin will appeal the verdict, who knows what will happen next. But it’s certainly thought-provoking and interesting.

Art is intriguing in the way it’s a commodity both in the commercial sense and in terms of national pride. Who wins out when an artists’ work becomes so important to the fabric of a society that ownership ceases to hold any power?

Should Botin have been allowed to do as he wished with the painting – so long as he wasn’t destroying it? Should Spain have given him a permit to sell the portrait and push the art market forward? We’ll see what precedent this verdict creates.