Protests against the Vietnam War occurred at almost half of all American college campuses. Antiwar student activist groups date back to 1900, but often diminished once the United States became involved. Opposition to the conflict was unique for its continued growth throughout the duration of the war. The mobilization of young Americans and their professors developed college culture, molding higher education institutions into forums for political involvement.

Introduction to the Vietnam War

Vietnam, then a colony of France, fought a war of independence from 1945 to 1954. The hostilities ended with a French withdrawal and Vietnamese liberation and division into a communist north and an anti-communist south. The United States began training South Vietnamese forces and providing military and logistical support after a civil war broke out in 1958.

An engagement between North Vietnamese patrol boats and a US Navy ship in 1964 resulted in false reports of a subsequent attack and the passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting President Lyndon B. Johnson authority to expand the war effort. Operation Rolling Thunder entailed air strikes into North Vietnam to destroy industry and transportation, but also caused many civilian casualties. This coincided with a heavy commitment of infantry, numbering over half a million by 1968.

Origins & Escalation of Student Protests

As the Soviet Union and the United States continued to militarize in the late 1950s, national organizations such as the Student Peace Union gained popularity. Early in the conflict, few acts of resistance happened as other issues dominated collegiate discourse. However, student activism favoring civil rights, ending atmospheric nuclear tests, and opposition to the Red Scare galvanized involvement and the formation of activist groups. Despite a slow start, antiwar sentiment steadily progressed in response to developments such as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and Operation Rolling Thunder and peaked after the Tet Offensive.

Tet is the Vietnamese lunar new year, which was usually a period of cease-fire during which people would travel to visit their families. This provided cover for the North Vietnamese to launch surprise attacks in January 1968. They struck deep into major cities but were quickly repelled, and territorial losses were retaken rapidly. Nevertheless, this demonstrated to the American public that the war was far from over despite President Lyndon B. Johnson’s assurances.

Were The Protestors All Hippies?

The hippie movement began on American college campuses, represented by people rejecting cultural norms. They opposed what they saw as overconsumption and materialism in favor of a communal, low-impact lifestyle. Early hippies were largely middle-class white people who resisted societal expectations such as grooming styles and pursuing a career, often opting for long hair and unemployment, sometimes working solely for the benefit of the hippie community.

They accepted rock and roll, psychedelic drug use, and spirituality and advocated for love and nonviolence. These sentiments grew popular among college students. However, hippies were often apolitical and were infrequent participants in Vietnam War protests.

Levels of Support & Increased Enrollment

If drafted, college men could use their attendance to defer their conscription in the Armed Forces. Although this was not a guaranteed method of avoiding service, enough sought it that one estimate suggests this policy raised enrollment by 4 to 6% in the late 1960s. The rate of men entering college rose in tandem with the number drafted from 1964 to 1968 and fell similarly from 1968 to 1973.

The percentage of college students who supported the war fell from 49% in the spring of 1967 to 20% by November 1969. A poll of the general population in this period showed more than half supported the war in March 1967, and only one-third did by 1968.

Professors Opposed the War Too

College faculty expressed opposition to the war as well. At the University of Michigan, professors organized a 12-hour teach-in in March 1965, where faculty criticized American policy to a crowd of students. Subsequent teach-ins spread nationwide, with one at UC Berkeley attracting 30,000 students. Support culminated in the National Teach-In on May 15th, where over one hundred schools participated thanks to radio and telephone communication. Despite a commitment from a White House delegate to debate at the conference, he dropped out at the last second. The teach-ins drew significant attention to the opposition movement and showcased its strength within the academic community.

Professors resisted the war in other ways. Several participated in criminal actions, such as helping individuals dodge the draft, and were subjected to FBI surveillance. Harvard law professor Alan Dershowitz taught a course on legal ways to avoid the draft. In response to growing movements for racial, gender, and environmental reform, academics guided existing professional associations or created new ones to support these causes.

Despite these radical actions, no known tenured professors were dismissed for their views on the war. Several were denied tenure yet could often land new positions as the expansion of the university system in the 1960s created a high demand for college educators.

Student Protests Go to the Supreme Court

Activism manifested in secondary education as well. Mary Beth Tinker wore a black armband in her public junior high school to commemorate the war’s dead on December 16, 1965. She and four other students were suspended and could only return if they agreed to do so without the armbands. Tinker wore black the remainder of the year in protest and filed a lawsuit, and the American Civil Liberties Union took up her case. After four years, the Supreme Court ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines that students have First Amendment rights in public schools for which they cannot be punished unless it hinders school activities.

It was initially unclear if this precedent applied at the college level. Collegiates at Central Connecticut State University attempting to form a chapter of Students for a Democratic Society were barred from official recognition. The school’s president claimed that the left-wing group went against the school’s values and would disrupt the learning environment. In 1972, the Supreme Court cited the Tinker case in its 8-1 ruling that individuals possessed their First Amendment rights on campus and that institutions could not withhold official status from a group solely because they disagreed with their stance. However, universities could still levy punishment if organizations disrupted educational opportunities.

Support for the War on College Campuses

Higher education was not unified against the conflict. Opponents of antiwar faculty members suggested that those in question were mostly of lower rank and belonged to fields of study only tangentially related, if at all, to political science. This claim was both upheld and rejected by a series of studies in the ensuing decade. Though this disparity seems to exist, one explanation is that prominent scholars already collaborate with officials and have a level of bearing on policy. Taking a public position almost inevitably required an oversimplification of the conflict, jeopardizing their existing influence, while newer educators could gain recognition for their stances.

Pro-war student groups existed as well, but in smaller numbers compared to their anti-war counterparts. Protests broke out in 1967 against Dow Chemical Company, the chief manufacturer of napalm, recruiting on college campuses. These demonstrations became violent at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with dozens injured by police batons for blocking the interviews. In the aftermath, more students than ever applied for Dow interviews and enrolled in the pro-war club Young Americans for Freedom.

Some schools stood to gain from the war. Southern Illinois University had been dispatching academics to Vietnam since 1961 and established a Vietnam Center to analyze a reconstruction policy and provide trained personnel to partake in it. They received federal funds for their contributions, which ignited significant student protests.

The Protests Escalate as the War Continues

Richard Nixon was elected President in 1968, promising to de-escalate the conflict, but by the fall of 1969, the patience of civilians and legislators wore thin. The Vietnam Moratorium Committee organized a series of demonstrations, vigils, and strikes on October 15, which brought out roughly one million protestors. The Committee contacted approximately 500 colleges in addition to individual students to mobilize support. This was followed one month later by a three-day “march against death” in the nation’s capital by 250,000 participants. College students were one of seven groups contacted for the rally.

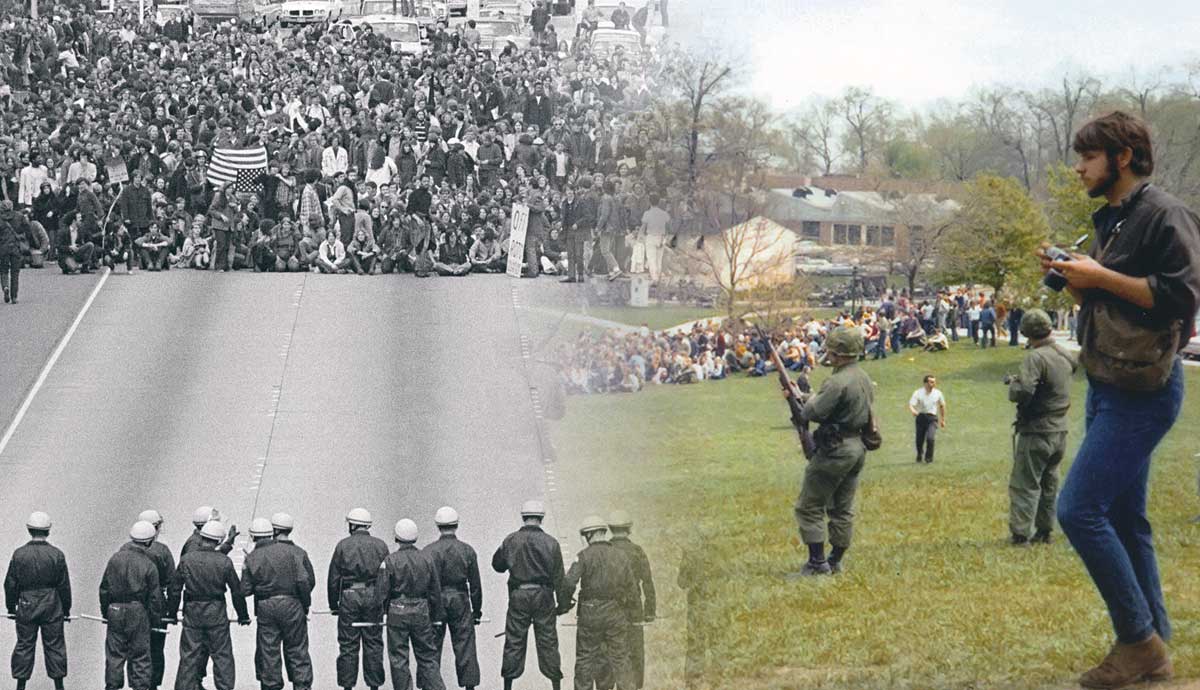

Protests turned violent at various campuses as demonstrators forcibly occupied buildings, destroyed property, and committed acts of arson and firebombing. Destructive actions occasionally spilled into neighboring communities. These represent extreme examples, but protests were met with force even in the face of lesser actions. College administrators worked with law enforcement to quell protests, and the use of tear gas, dogs, and other crowd control measures were sometimes deployed disproportionately.

The Tragedy of the Kent State Massacre

Nixon announced an invasion of Cambodia to target North Vietnamese supplies in April 1970. College protests erupted nationwide the next day, with one in Kent, Ohio, resulting in fires being lit in the streets and police cars being struck by bottles. The protests were dispersed by tear gas, and the next day, the governor called for the assistance of the National Guard. By the time these troops arrived, they found Kent State University’s ROTC (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps) building burning as some protestors interfered with firefighting efforts.

On May 4th, 3,000 activists assembled across from 500 guardsmen in the school’s Commons. Policemen ordered the crowd to evacuate and fired tear gas, which caused them to retreat across a hill. Members of the National Guard followed the demonstrators and briefly became caged in a fenced football field where students threw rocks at them for ten minutes. The troops retreated to the top of the hill, where several discharged their weapons. Most aimed around the crowd, but some fired directly at them. In thirteen seconds, thirteen students were hit, and four did not survive. This provoked a significant response from the demonstrators, who advanced upon the Guard, and hostilities only ended when a body of faculty implored the students not to risk their lives any further.

De-Escalation & Impact on College Culture

In response to the expansion of the war and the Kent State massacre, a nationwide college strike occurred. Eight hundred eighty-seven schools saw protests, ninety-seven canceled classes, and twenty did so for the rest of the semester. This represented the last significant point of widespread opposition as protests de-escalated along with American military commitments.

President Nixon announced in early 1973 that the belligerent nations agreed upon a cease-fire, and the last American units left by the end of March. The US continued to support the South Vietnamese until their eventual defeat at the Fall of Saigon in 1975. Vietnam was united under a communist government after decades of conflict, claiming the lives of 60,000 Americans and two million Vietnamese. Faculty and students celebrated the end of the war.

Student activism quieted in the following years yet persisted in response to the invasion of Grenada. Nevertheless, by 1988, antiwar and political organizations had disappeared from most colleges. The increased enrollment, activism, and political mobilization of higher education spawned by the Vietnam War manifests in college culture today as students, faculty, and administrators express and debate societal issues.