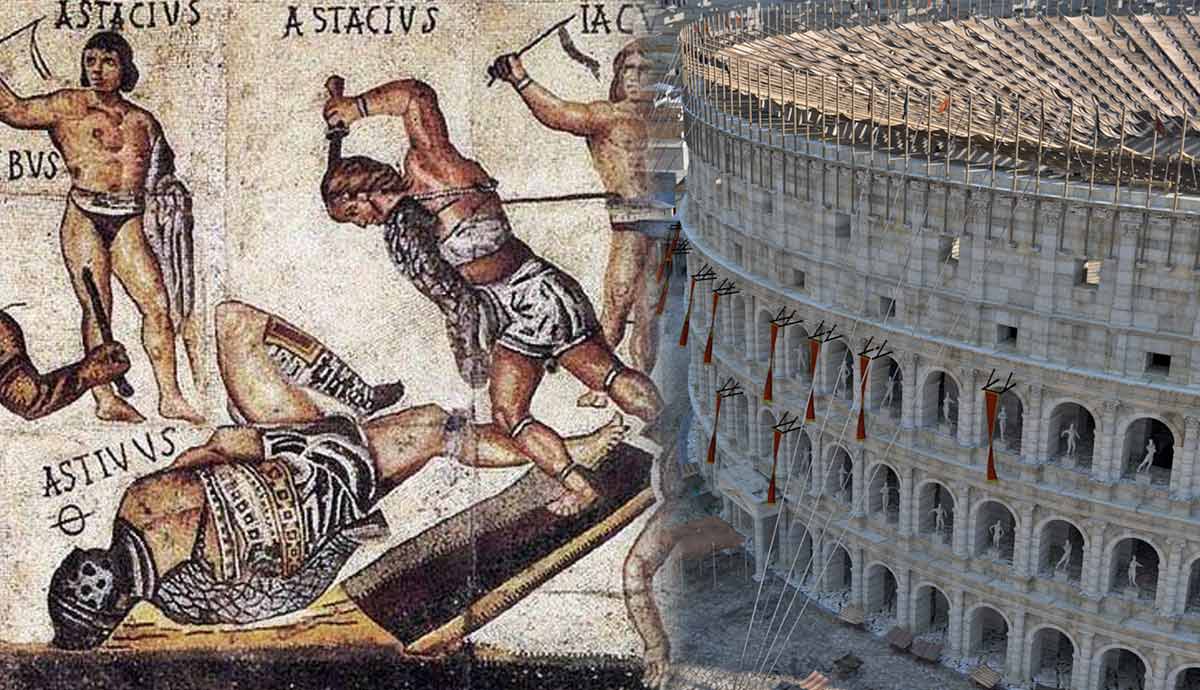

The Colosseum, arguably Rome’s best-known monument, was completed during the reign of the emperor Titus in 80 or 81 CE and inaugurated with 100 days of games and spectacles. We know quite a bit about these games from a variety of sources, especially a group of epigrams written by the Roman poet Martial to celebrate the event, known as the Liber de Spectaculis. If you were in Rome during the inaugural games of the Colosseum, what kind of lavish spectacles would you expect to see? From gladiatorial bouts to exotic animals to historical re-enactments, this is what passed for entertainment in Rome in the 1st century CE.

Dedication of the Flavian Amphitheater

Unlike other entertainment arenas around Rome, such as the Circus Maximus, which was on the city’s outskirts, the Colosseum was centrally located in the ancient city of Rome. This was made possible by the infamous Great Fire of Rome in 64 CE, which destroyed what had previously stood there. This occurred under Nero, who initially claimed the space for himself to build his elaborate palace known as the Domus Aurea or “Golden House.”

Vespasian emerged, at the end of 69 CE, as the victor of the civil war that had raged since the defeat and death of Nero near the start of 68 CE. He spent the next decade establishing the legitimacy of his new Flavian Dynasty and restoring traditional Roman values; values promoted by Augustus but corrupted by the time of the last Julio-Claudian.

He started his reign by reinforcing the military credentials of himself and his son and successor Titus by celebrating an elaborate joint triumph in Rome in 72 CE for their successful war to put down revolt in Judea. As part of this triumph, Vespasian pledged to use the spoils of war to build a new amphitheater in Rome to host public entertainment, providing the people with the “bread and circuses” they craved. To reinforce the idea of himself as a generous patron to the people of Rome, he tore down Nero’s Domus Aurea to make space for the stadium, returning the land to the people.

That this idea was made explicit in the propaganda of the day is confirmed by an epigram written by the contemporary poet Martial about the dedication of the Colosseum. He sought imperial patronage and wrote sycophantic poetry about Titus, so his poem probably reflects what the Flavians wanted people to think.

“Here where, rayed with stars, the Colossus views heaven anear, and in the middle way tall scaffolds rise, hatefully gleamed the palace of the savage king, and but a single house now stood in all the city. Here, where the far-seen amphitheater lifts its mass august, was Nero mere. Here, where we admire the warm baths, a gift swiftly wrought, a proud domain had robbed their dwellings from the poor. Where the Claudian Colonnade extends its outspread shade the palace ended in its furthest part. Rome has been restored to herself, and under thy governance, Caesar, that is now the delight of a people which was once a master’s” (De Spectaculi 2).

The amphitheater would only be completed as far as the third level when Vespasian died in 79 CE. It was swiftly completed by his son and successor Titus in 80/81 CE. He also built the Baths of Titus alongside the Colosseum, referenced by Martial above. When it was dedicated, the Colosseum was known as the Amphitheatrum Caesarum. It would later become known as the Colosseum due to its proximity to a colossal statue of Nero.

Inauguration of the Colosseum

The Colosseum was inaugurated with at least 100 days of games by Titus in either 80 or 81 CE. This was good timing for extravagant games. Titus had not long been emperor and wanted to boost his popularity after making himself decidedly unpopular as praetorian prefect under Vespasian. The Roman people were also in need of a pick-me-up since another great fire had burned in Rome in early 80 CE, and Vesuvius had erupted in 79 CE, destroying several Italian cities.

The spectacular games hosted by Titus are the subject of Martial’s Liber de Spectaculis, which was probably written during the games and published shortly before the death of Titus in 81 CE. The suggestion that the poems were written a few years later about different games held under Titus’s brother Domitian has now been dismissed. But it is interesting that while Domitian surely accompanied his brother to the games, he is not mentioned in any of Martial’s poems about them.

What to Expect From a Day at the Games

What could the average Roman expect from a day at the games? First, not everyone would have been able to attend. While the Colosseum seated an impressive 60,000-80,000 people, the population of Rome at the time was at least one million, and Martial refers to people coming from across the empire to see the games. While seats would have been reserved for senators and others of importance, others would probably have obtained their tickets by lot, not unlike getting a ticket to the modern Olympics.

Tickets were made of wood, terracotta, or bronze, and they directed the holder to the right entrance for their seat. While senators had the good seats at the bottom close to the action, the common folk were sent to the “nosebleed” seats at the top, where the view might not have been great, but the atmosphere was electric. Don’t forget to bring your own seating cushion for comfort. Spectators would have walked past many impressive statues and colorful reliefs to reach their seats, sending messages that the Flavians wanted to communicate.

A day at the games would have been a full-day affair. The program usually started with animal spectacles in the morning, executions around lunchtime, and either gladiatorial fights or historical re-enactments in the afternoon. These shows went on whether there was sunshine or rain, and canopies operated by sailors were extended over the open arena to protect the spectators.

Since it was a full day, of course, you could get a bite to eat. Food vendors were probably plentiful and the remains found in the sewers suggest that people ate chicken, shellfish, olives, nuts, and fruits like peaches, cherries, and grapes. Pot shards also suggest that wine was consumed, and there is evidence of public water fountains around the stadium. Of course, there were bathrooms, but they were probably quite unpleasant by the end of the day, just like today.

Tickets weren’t just valuable for seeing the spectacles, they also gave people the opportunity to receive the generosity of the emperor. It seems likely that goods, such as bread, were handed out freely at the games, and donatives were sometimes made to all spectators. We also know from Cassius Do that during these games, Titus threw wooden balls inscribed with specific gifts from his seat into the crowd. Those lucky enough to grab one could exchange the ball for the corresponding gift with officials. Prizes included food, clothing, slaves, horses, cattle, gold, and silver. The emperor made a spectacle of himself as a philanthropist during the games (66.25).

Morning Entertainments: Animal Spectacles

Traditionally animal entertainments were held at the start of the day, and this also seems to be the case with the games held by Titus. According to Cassius Dio, 9,000 tame and wild animals appeared at the inaugural games (66.25). He specifically mentions hunts involving cranes and elephants, while Martial mentions a variety of other animals including lions, leopards, tigers, hares, pigs, bulls, bears, a wild boar, a rhino, buffalo, and bison.

It seems that considerable expense was spent to find and train animals. In one of Martial’s epigrams, he recalls a tiger gently licking the hand of its trainer after just tearing a lion apart in a rage:

“The rare-seen glory of the Hircanian land, a tiger, wont to lick his master’s hand, in pieces tore a lion in his rage, a thing not known before in any age. He durst not this attempt in forests high, beasts among men learn greater cruelty” (De Spectaculis 18).

Martial also celebrated a famous bestiarius named Carpophorus. A bestiarius was one of the specific types of gladiators who trained to perform in the arena:

“A boar Meleager which gave thee a name, adds little to Carpophorus his fame; who a vast bear, rushing upon him, flew, the northern clime a fiercer never knew; a lion, which became Alcides hand, of immense bulk he laid upon the sand; also a part: and when the Prize was won, he still was fresh, and could yet more have done” (De Spectaculis 15).

Martial also describes an incredible moment when an elephant, seemingly of its own accord without training, turned and bowed before the emperor. Martial implies that the animal could feel the power and divinity of the emperor. The reality is that the animal probably was trained, and this formed part of the spectacle, of which the emperor was an integral part. According to Martial:

“That thee an elephant suppliant did adore, who stroke with terror a fierce bull before, to keeper’s art, cannot imputed be; we must ascribe it to thy deity” (De Spectaculis 17).

Midday Executions

Executions were usually organized for lunch when the sun was at its hottest. This was one part of the spectacles the emperor was not involved in. Traditionally, senators left for lunch during the executions and returned. We know this because Suetonius criticized the emperor Claudius for staying to watch. Titus, doing his best to set an example, was almost certainly not present during the executions at the inaugural games.

Executions were usually carried out as crucifixions or maulings by wild animals. But they were also sometimes done as more elaborate re-enactments of stories from mythology. Martial describes two such shows as part of the games held by Titus. In the first, the re-enactment was of Prometheus, the Titan who was cursed to have his liver eaten by a carrion bird each day, only to grow back and be eaten again. But as well as referring to the myth, Martial refers to a mime presentation of this punishment that happened under Caligula, which was now made real in the Colosseum:

“As, fettered on a Scythian crag, Prometheus fed the untiring fowl with his too-prolific heart, so Laureolus, hanging on no unreal cross, gave up his vitals defenseless to a Caledonian bear. His mangled limbs lived, though the parts dripped gore, and in all his body was nowhere a body’s shape. A punishment deserved at length he won — he in his guilt had with his sword pierced his parent’s or his master’s throat, or in his madness robbed a temple of its close hidden gold, or had laid by stealth his savage torch to thee, O Rome. Accursed, he had outdone the crimes told of by ancient lore; in him that which had been a show before was punishment” (De Spectaculis 7).

Martial also refers to a re-enactment of the punishment of Orpheus, who was torn apart by a group of women in Greek myth:

“What in the Thracian Mount’s of Orpheus told, thy theater, great Caesar, did unfold, the rocks were seen to move, the woods to run, when to his harp the wondrous minstrel sung; together with the tree, the beasts were led, and hovering birds circled his sacred head. At last a bear the prophet piece-meal tore, acted in truth, what fabled was before” (De Spectaculis 21).

Naumachia Sea Battles

Another form of entertainment that was popular in Rome was the Naumachia, which were re-enactments of famous naval battles. In the previous hundred years, several purpose-built theaters that could be flooded had been constructed for this purpose. The most famous was an artificial lake made by Augustus.

Writing about Titus’s games, Cassius Dio says that Naumachia shows were presented both at Augustus’s maritime arena and in the Colosseum. Suetonius says that they took place on an artificial lake, but gives no further details. Martial too talks about the Naumachia shows but does not give a location. He does mention that the stadium where they were held was flooded and drained on the same day. This suggests that the shows probably took place in Augustus’s artificial lake arena that was designed for this purpose, but the Colosseum may also have had this technology:

“Whomever you are who come from distant shores, a late spectator, for whom this sacred day is your first, that this naval battle with its ships, and the waters that represent seas, may not mislead, I tell you ‘here but now was land.’ Believe you not? Look on while the seas weary the God of war. Wait one moment – you will say ‘here but now was sea’” (De Spectaculis 24).

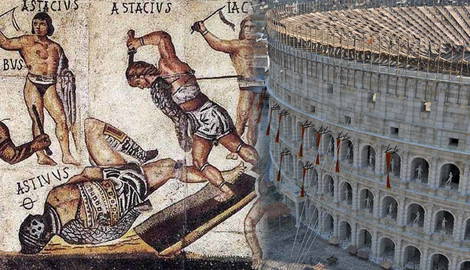

Afternoon Gladiatorial Combats

While some of these shows would have happened in the afternoon, most afternoons were reserved for the extremely popular gladiatorial combats. Gladiators trained at schools set up near the Colosseum in the former grounds of the Domus Aurea to participate in these great games.

Martial only gives details of one gladiatorial match, between the veterans Verus and Priscus, but it is a significant account:

“Priscus and Verus, while with equal might, prolonged an obstinate and doubtful fight, the people, oft, their mission did desire; but Caesar from the law would not retire, which did the price and victory unite, yet gave them what encouragement he might; largess of meat and money did bestow, which also among the people he did throw. In the end, however, the strife was equal found, both fought alike, and both alike gave ground: So that the palm was upon each conferred, their undecided valor this deserved. Under no prince before we ever did see, that two should fight, and both should victors be” (De Spectaculis 29).

The poem recounts how the fight between the two veterans was a stalemate and the audience cheered for both. Rather than demand that they keep fighting and respond to the audience, Titus declared both winners. This was not the same as sparing their lives so that they could return to fight in the arena again. Instead, both were granted a wooden sword, which represented their freedom. It is this granting of freedom, rather than just clemency, that Martial says was unique to his prince Titus.