Written in 1848 by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto was published during a year of widespread revolutions throughout Europe. This document manifested the very presence of what Marx and Engels called “a specter that haunted Europe:” communism. Although there have been proto-communist movements throughout history, The Communist Manifesto defined communism in its modern sense. Since its publication, the Manifesto has inspired countless political movements, and a century later, the world was divided into two blocs, with one claiming to follow its principles. Whether the Manifesto has changed the world for the worse or whether states truly embraced these principles remains a topic of controversy. However, one thing is certain: It shaped the course of human history.

The Communist Manifesto and Karl Marx’s Philosophy

The Communist Manifesto—originally titled Manifesto of the Communist Party—was written by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in 1848 on behalf of the Communist League. Although Engels is the co-writer of the pamphlet, Marx was the one who developed the main theoretical foundation. Engels acknowledged that in his preface to the 1883 German edition: “The basic thought running through the Manifesto…belongs solely and exclusively to Marx.”

Indeed, Karl Marx’s other works contain more detailed theoretical expositions of the points briefly touched upon in the Manifesto. Marx’s theory of history—summed up in the first chapter of the Manifesto—can be further examined in The German Ideology.

Another important theme from the Manifesto, a critical economic analysis of capitalist society, is the main focus of Marx’s magnum opus, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. The significance of the Manifesto, however, lies not in its theoretical richness, but in its simplicity and call to action.

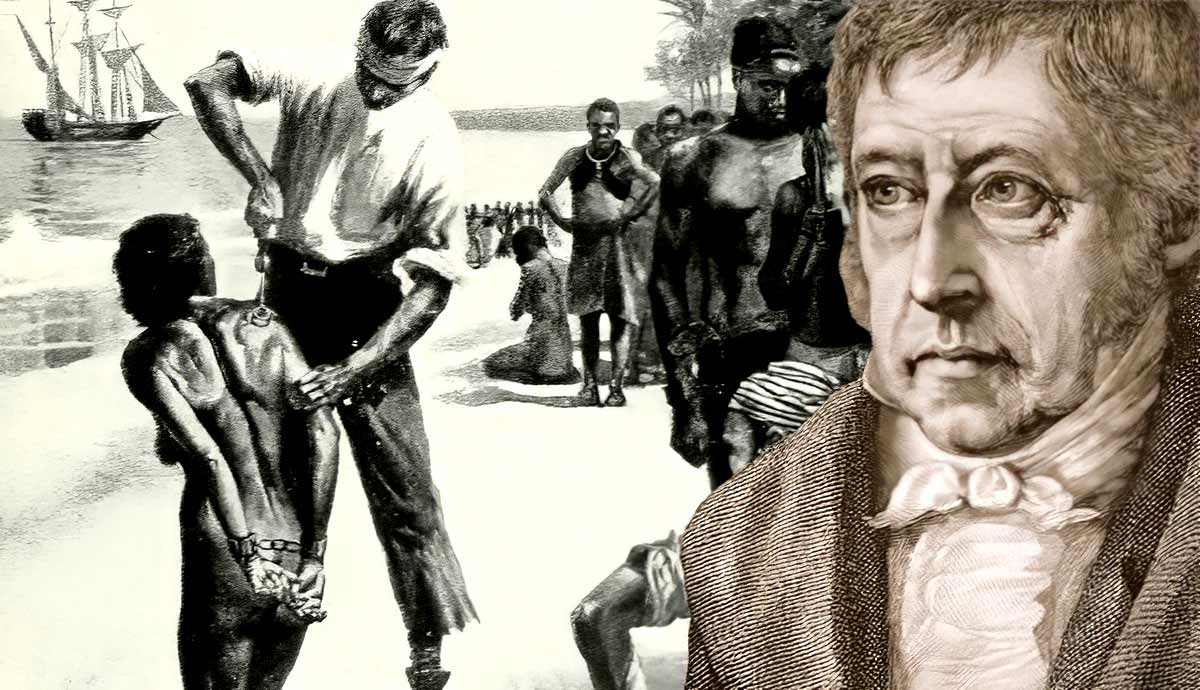

Alongside French socialist literature and classical political economy, a major influence on Marx’s thinking was German idealist philosophy—especially Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s work. While both Hegel and Marx were mainly concerned with human freedom, Hegel believed that modern society’s organization had secured the conditions necessary for it. For Hegel, actualizing freedom was rather a subjective matter—individuals had to recognize their role in the rational social order. For Marx, the problem was an objective one—the material conditions of the real world needed to be changed.

The Communist Manifesto, therefore, expresses the significance that Marx gives to action, as opposed to the purely theoretical philosophy that preceded his own. The Manifesto, in that sense, should be considered in relation to his famous 11th thesis from Theses on Feuerbach:

“The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.”

(Marx, 1845)

The Historical Context of The Communist Manifesto

What prompted Marx and Engels to write this manifesto? First of all, they were tasked with preparing a manifesto for the Communist League, a German political party of which they were members. Thus, it should always be kept in mind that this document is just a manifesto, not a comprehensive academic study.

Significant works belonging to the socialist tradition existed prior to Marx. The writings of Gerrard Winstanley, François-Noël Babeuf, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau are some early examples, although they were not fueled by powerful political movements.

Substantial working-class movements that possessed the ability to wield significant political power only emerged during the 19th century. The emergence of this fresh political power brought along a collection of socialist writings by Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, and Henri de Saint-Simon. Labeled as utopian socialist in The Communist Manifesto, these texts would eventually be surpassed by the much more profound and systematic works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. In a way, this was an attempt to transform socialism from being utopian to scientific.

A need for the publication of such a manifesto can also be derived from the development of Marx’s thought.

Karl Marx lived in the 18th century, a time when the Industrial Revolution was reshaping society. The rise of industrial capitalism led to the emergence of a modern working class. The working class was crushed under poor working conditions, low wages, excessive working hours, and the systematic usurpation of profit by the capital owners.

In Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844, Marx argued that workers experienced alienation as they lost control over their work in the capitalist mode of production. In order to understand this socio-economic transformation, Marx looked at history and saw patterns as presented in The German Ideology. These patterns, he argued, not only explained the development of modern society but also showed us the way forward. He thought that this system of exploitation could only be overcome through collective action. That’s why, as mentioned in the preamble of the Manifesto, it was time for communists to openly declare their views and goals.

Historical Materialism and Class Conflict

“The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles.”

(Marx & Engels, 1848)

This is the opening phrase of the first chapter of The Communist Manifesto, which sums up Marx’s theory of history—historical materialism. Since his early intellectual years, Marx was particularly interested in Hegel’s dialectics, which involved understanding change through a conceptual resolution of contradictions.

Marx formulated Hegel’s abstract dialectical method in materialistic terms to comprehend historical changes. In this view, the organization of human society is determined by how people produce their means of life. The mode of production of society at some point in history created a class division, in which one class exploits the producer. When the forces of production develop to a point where it is no longer compatible with the existing relations of production, a revolution occurs. Marx’s explanation of the transformation of primitive societies into slave states, feudal societies, and ultimately capitalist states involves these successive revolutions.

Therefore, the opposing forces that drive history in Marx’s and Engels’ theory are classes. In every epoch in history, they argued in the Manifesto, there were social classes that opposed each other as the oppressor and the oppressed. This relationship manifested itself differently in different eras as each mode of production has its own internal dynamics: Free men and slaves, patricians and plebeians, lords and serfs, bourgeoisie and proletariat.

As the mode of production of a society progresses, it confronts new contradictions that result in its replacement by a superior economic structure. For example, feudal lords had to engage in trade in order to augment their wealth. However, this led to the rise of a merchant class, which demanded political rights and triggered the emergence of mercantilism, a precursor to capitalism. In the end, the feudal mode of production was abolished as it no longer supported the further development of the forces of production.

Capitalism Produces Its Own Grave-Diggers

Marx and Engels argued that the bourgeoisie was unique in its demand for constant change in the productive forces. This is in contrast with the older oppressive classes:

“The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionizing the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society. Conservation of the old modes of production in unaltered form was, on the contrary, the first condition of existence for all earlier industrial classes. Constant revolutionizing of production, uninterrupted disturbances of all social conditions, everlasting uncertainty and agitation distinguish the bourgeois era from all earlier ones”

(Marx & Engels, 1848)

Here, Marx and Engels emphasize how capitalism necessitates the constant enhancement of productive forces to improve the efficiency of labor for maximum profit. The very nature of the capitalist system imposes on capital the requirement to accumulate wealth and pursue profits endlessly.

However, in continuously revolutionizing the forces of production and endlessly seeking capital accumulation, the bourgeoisie prepares its own end. As the bourgeoisie, or capital, develops, so too does the proletariat. These laborers, as the authors point out, survive so long as they find work, and can only find work if their labor contributes to capital accumulation. In essence, they become commodities that must compete by selling themselves.

But as industrialization progresses, the proletariat not only increases in number but also becomes more concentrated and aware of its growing strength. While Marx and Engels did not believe that the proletariat was ready to engage in conscious collective action, they recognized its development. As industrial development continues, the proletariat would transform into a class and ultimately achieve class consciousness, leading to the formation of a political party. Marx and Engels interpreted this tendency as capitalists producing their own gravediggers.

Communists and the Vision of Socialist Revolution

In the next chapter, Marx and Engels clarify the relationship between communists to the working class. The communist party, they argue, does not oppose any working-class party or represent a particular group of workers. Rather, it expresses the general will of the international proletariat. The short-term goal of this party is a socialist revolution to establish the basis for a communist society where property, class, and state no longer exist.

According to Marxist dialectical materialism, capitalism is followed by socialism, where the means of production are owned and controlled by the workers. In socialism, exploitation is eliminated; workers now have control over their labor and its product.

In communism, alienation is eliminated; work becomes a meaningful end in itself. In order to achieve the short-term goal of establishing socialism, Marx and Engels attribute certain demands to the communist party. Among them are the abolition of private property and inheritance, a progressive income tax, free public education, abolition of child labor, and centralization of means of communication and transport.

Marx never provided a clear description of what a communist society would look like, as he thought that it would naturally emerge from the dialectical course of history. He did, however, briefly mention the nature of labor in Comments on James Mill, which is an intriguing text.

The following chapter contains a distinction between Marx’s and Engels’ communism and other forms of socialist thought: Reactionary socialism, conservative or bourgeois socialism, and critical-utopian socialism and communism. These doctrines are rejected for advocating different forms of reformism and failing to recognize the leading revolutionary role of the proletariat.

In the remaining parts of the document, Marx and Engels discuss the position of communists on specific struggles in various countries. They conclude the manifesto with their famous call for international action:

“Workers of the all Lands, Unite!”

The Lasting Influence of The Communist Manifesto

The publication of The Communist Manifesto coincided with the Revolutions of 1848. Although these revolutions were not anti-capitalistic in nature, the manifesto was produced in that particular revolutionary climate.

With the failure of these anti-monarchical revolutions, the Manifesto fell into obscurity for 20 years. It lost the little reputation that came with the role of Neue Rheinische Zeitung during the revolutions, the newspaper of the Communist League. The pamphlet experienced a revival in the 1870s, thanks to Marx’s leadership in the First International. During the next four decades, as social-democratic parties gained prominence all over the world, the Manifesto was also printed in hundreds of editions in thirty different languages.

The October Revolution of 1917 broke out in Russia, where capitalism was not yet fully developed, contrary to the predictions made in the Manifesto. It did, however, pave the way for the international ubiquity of the Manifesto.

As the first socialist state in history, Bolshevik Russia was established along Marxist lines. From then on, Marxist parties began to require their members to have read essential works such as the Manifesto. Marxism-Leninism, a version of Marxism modified by the Bolsheviks, became the state ideology of the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, and many countries in the Third World during the Cold War.

Even in the capitalist West, other currents of Marxism, such as Western Marxism, were highly influential for leftist intellectuals and major political parties. Even after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, The Communist Manifesto is still ubiquitous. It is estimated to have sold around 500 million copies in total.

The influence of Karl Marx’s thought is still far-reaching, spanning academic disciplines, political movements, and art forms. The Communist Manifesto, as the most widely read, simple, and accessible work of Marx, is likely to remain the go-to introduction to Marxism.