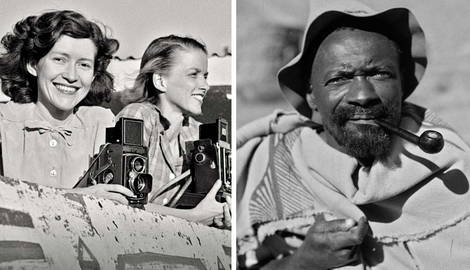

Although born in Cornwall, England, Constance Stuart was South Africa’s first war correspondent. At a young age, she was already well-traveled and had a love for photography. This love helped bring some of the most enduring images to the world’s attention, focusing on beautiful people and places and of course, the exploits of the South African soldiers who fought up the boot of Italy in World War II.

Early Life of Constance Stuart

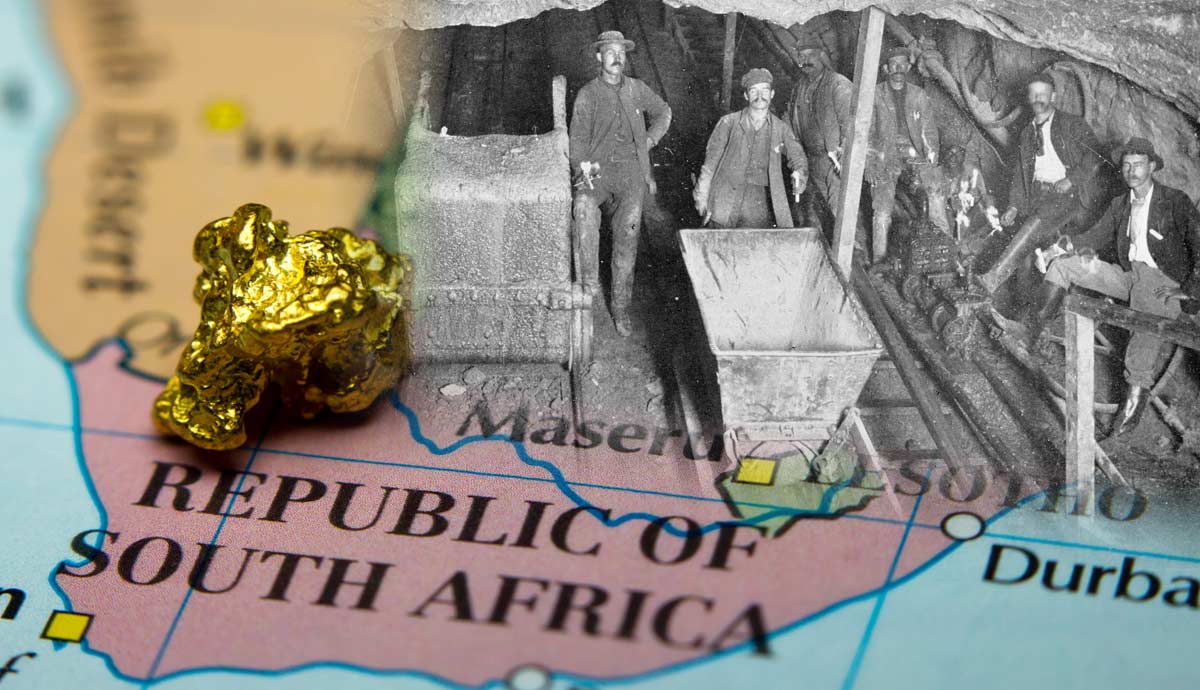

On August 7, 1914, Constance Stuart was born in Cornwall, England. Three months later, her family relocated to South Africa. Constance lived with her family on a tin mine in the Transvaal, where her father worked as a mining engineer. Stuart grew up in Pretoria, and for her tenth birthday, she received a Kodak Box Brownie camera. A few years later, in 1930, she exhibited eight photographs at the Pretoria Agricultural Society Show during the Boys and Girls Achievement Week. Her images won her first place in the competition.

It was no surprise that Constance Stuart had a love for photography, as it seemed to run in the family. Back in Cornwall, her maternal grandfather ran a successful photographic studio.

In 1933, Constance Stuart decided to further her study in the field and left for England to attend school at the Regent Street Polytechnic School of Photography in London. She gained immense experience during her time there and apprenticed at two professional portrait studios under the tutelage of renowned photographers based in Berkeley Square and Soho.

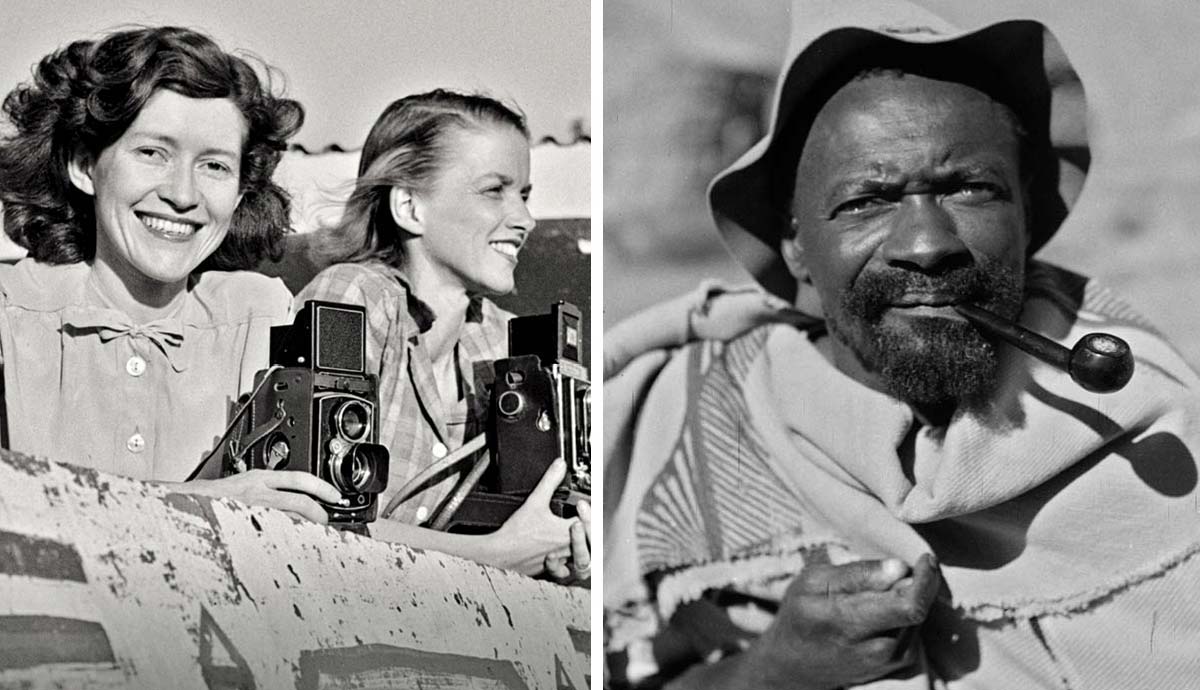

In 1936, her studies took her to Germany, where she studied at the Bayerische Staatslehranstalt für Lichtbildwesen (Bavarian State Institute for Photography) which taught a modernist approach to photography. During her education in Munich, Stuart discovered the Rolleiflex camera, which she continued to use throughout her career. In Munich, she also evolved her pictorial style, discarding the romantic for an ordered approach to black and white photography free of manipulation.

Return to South Africa

Constance Stuart returned to South Africa in 1936 and opened her own business, the Constance Stuart Portrait Studio in Pretoria, where she focused on portraiture. Stuart became well-known in her field and photographed many famous people in society, from statesmen to artists to generals. In 1944, her first solo exhibition, The Malay Quarter, was opened by the esteemed English playwright Noël Coward. The exhibition focused on an area of Cape Town inhabited by the Cape Malay people. In 1946, she opened a second studio in Johannesburg.

From 1937 onwards, she developed an interest in photographing the ethnic cultures of Southern Africa. She toured the region, photographing people from cultures such as the Ndebele, Zulu, Sotho, Swazi, Lobedu, and Transkei. Exhibiting these photographs caught the attention of Libertas Magazine, which appointed her their official war correspondent.

In particular was her photography of the Ndebele people, known for their colorful architecture and decorative clothing. For Constance Stuart, living in Pretoria, it was easy to interact with the Ndebele people, as many Ndebele lived as indentured servants in and around Pretoria and worked on the surrounding farms. They were also not unused to the camera. Their unique and beautiful tribal aesthetic had drawn many artists, photographers, and other tourists over the years.

She would drive out to the settlements with her friend, Alexis Preller, who was a sketch artist, and the two of them would set about capturing the aesthetic aspects of Ndebele culture. Despite being known for their colorful designs, Constance Stuart captured her images in black and white, thus focusing on the form and design of the Ndebele culture, rather than the expression of color.

Between 1944 and 1945, Stuart was attached to the US 7th army in its duties in post-war Europe. Under the command of the US 7th Army was the 6th South African Mechanized Infantry Division, on which she was specifically tasked with reporting. She spent much of her time in the Italian Apennines, where the division was stationed. Despite this, Stuart went above and beyond her duties, photographing soldiers from many other nations, as well as civilians and devastated towns. It was during her time as a war correspondent that she met the man who would become her husband. Colonel Sterling Larrabee was working as the US military attaché to South Africa at the time, and the two struck up a friendship.

Being a woman in a war zone, however, had its challenges. She had to have separate sleeping quarters organized, which were often very uncomfortable, and she was kept away from the front lines for longer periods than her male counterparts. Constance Stuart, however, overcame the difficulties, and was well respected by everyone around her. In 1946, she published a compilation of her photographs from this journey into a photographic diary called Jeep Trek.

1947 was an auspicious year for Stuart, as the British Royal Family were to tour Southern Africa in a six-month-long tour, for which she had been chosen as the official photographer. Apart from South Africa, they visited Basutoland (now Lesotho), Swaziland, and Bechuanaland (now Botswana) which were British Protectorates. The opportunities for ethnic imagery were perfect as many people from these territories donned their traditional garb to meet the Royals.

In 1948, the National Party came to power and instituted strict policies of racial segregation, which would later evolve into apartheid. Stuart, whose photographic subjects were primarily Black people, found this situation deplorable and decided to move to the United States to continue her life and career.

Life in the United States

Stuart moved to New York, where she met with Sterling Larrabee again. The two later got married and moved to Chestertown, Maryland. She focused her photography on the regions of New England, including Tangier Island and the rest of Chesapeake Bay. Naturally, having changed her location, Stuart’s subjects changed too, but she retained her casual and comfortable style. However, she didn’t only photograph human subjects. Stuart spent much time photographing the Eastern Shore landscapes, including both natural and man-made subjects such as boats and boatyards.

In 1955, The American Museum of Natural History in New York displayed her first exhibition since moving to the US. The exhibition was a showcase of the tribal women of South Africa, and gained Larrabee much attention. She established a lasting connection with Washington College, where she established the Constance Stuart Larrabee Arts Center. Constance passed away at the age of 85 in July 2000.

The legacy of Constance Stuart Larrabee’s Photographic Style

Constance started out using low angle shots, partly because her first Kodak Box Brownie camera was designed to be used at torso-height. With her Rolleiflex camera, she continued with the style, holding it at chest height and thus being able to converse with her subjects without the barrier blocking her face. The result was that she could capture the subject in a more relaxed and natural state. It was a style that lasted and was a common feature in her photography. And although a lot of what Stuart did was documentation, it was also a showcase of art. Especially with her photography of native South African Black people, it was an exercise in expressing humanity from a country where the subject was cruelly dehumanized. After the war, Stuart joined social welfare groups which took her, through charity, to the people she wanted to photograph.

Stuart’s documentation-style photographs accompanied her portraiture, and told narratives from a distance. Removing herself from the subject, her images captured stories of people in urban settings, and notably, in the mines of South Africa. Although she refused to speak about her political views nor consciously infuse political opinions into her photographs, the political nature of the subject shone through simply because of the subject matter.

Stuart’s photography, nevertheless, was considered art by all who commented, including the South African media and the Minister of Native Affairs. After moving to the United States and subsequently having her photographs exhibited there, Stuart’s work became virtually exclusively classified as art, divorced from the context, and thus ignored any semblance of political meaning. In the modern era, political sentiment has been re-inserted into her photographs as a way of addressing the history of a nation mired in racial politics. Doing so gives a voice to the pictures’ subjects and re-assesses ownership.

However, adding the political does not divorce the subject from the art. Constance Stuart Larrabee’s photographs serve as a depiction of ethnography, art, and the pervasive politics which cannot be avoided in any form of historical depiction.