Constantine the Great is undoubtedly one of the most famous Roman Emperors. He was made emperor while in Roman Britain, fought a war against Emperor Maxentius in Rome, and then took control of the entire Roman Empire. Interestingly, there is some evidence that he returned to Britain just two years after he left to fight Maxentius to fight a major military campaign there. But this campaign is rarely mentioned in the histories of his life and triumphs. What is the evidence for this largely forgotten invasion of Britain, and does it appear in any written records?

Chronology of Constantine the Great in Britain

To begin, it would be helpful to establish a timeline of events surrounding Constantine the Great’s original departure from Britain. He reportedly arrived in Britain in 305 CE, accompanying his father, Constantius Chlorus, or Constantius I, who was the emperor of a large portion of the West, including Britain. They were campaigning in the north against the Picts. When his father died in 306 CE, Constantine was declared emperor, a move that was immediately accepted in Britain and Gaul but took a few extra years in Hispania. He stayed in England for several months, driving back the Picts and reconstructing many military bases.

Later that year, Constantine left Britain to deal with an attack of Frankish kings near the Rhine. At about the same time, Maxentius declared himself emperor in Rome in opposition to Constantine. However, Constantine did not engage in direct conflict with him. Rather, he withdrew to Britain. Over the next few years, he focused his attention primarily on Britain itself and on nearby Gaul, particularly the region of the Rhine. As time went on, Constantine grew increasingly powerful.

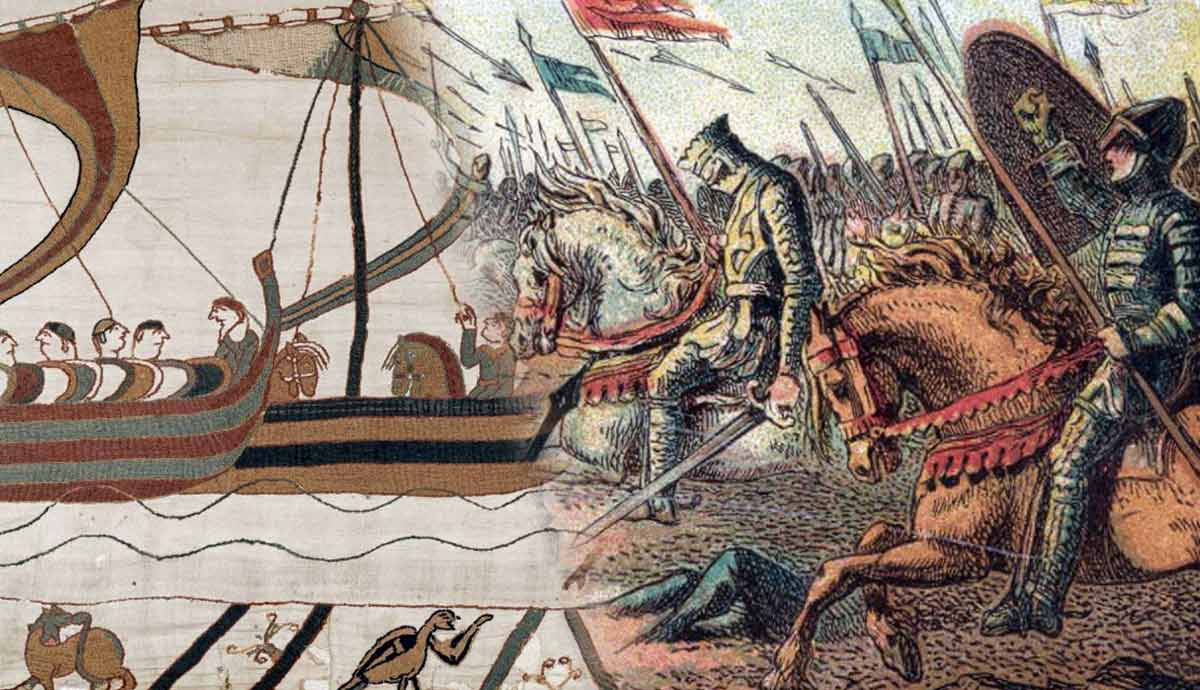

In 311, war broke out between the various strongmen across the Empire who were vying for imperial power. Constantine, who had been acquiring more support from the people of Britain and Gaul, went to war against Maxentius in Italy. The two men finally clashed in 312. Famously, Constantine won this battle, overthrew Maxentius, and killed him. This was the Battle of Milvian Bridge, in which Constantine supposedly saw a cross in the sky, leading to his favorable view of Christianity.

This did not immediately result in Constantine becoming the sole emperor of the Roman Empire. Nevertheless, this was an important part of the process. Over the next 12 years, Constantine continued fighting against his rivals in various important battles. It is with this background that we can now examine the issue of Constantine’s forgotten invasion of Britain. The evidence suggests that soon after he defeated Maxentius, Constantine returned to Britain to engage in an important campaign there. What is this evidence?

Numismatic Evidence

The evidence for this event is perhaps the most contemporary evidence of all, even more so than documents written by contemporary Roman historians: numismatic inscriptions. What exactly does this coinage evidence show? On a series of coins that were minted in Roman London in 313-314 and 314-315, we find the words “ADVENTVS AVG.” In other words, these coins proclaimed the upcoming and present advent, or arrival, of the emperor. In this case, the emperor in question was Constantine.

This shows that in the year 314, Constantine the Great returned to Britain. Why did this happen? News of the journey must have been known in 313 for the minters in London to start producing coins, but this was not long after Constantine’s defeat of Maxentius. While an important victory, this was not the end of the civil war. Surely, for Constantine to return to Britain, he must have had a very good reason.

Logically, one compelling reason to return to Britain would be if there had been a major rebellion there. It would have had to have been significant enough that it justified Constantine’s return in the midst of a civil war throughout much of the Roman Empire. Although there are no contemporary records that describe this event, there is good reason to believe that it happened. As well as the simple fact that Constantine returned to Britain in such a crucial period, there is further coinage evidence worth looking at.

In coins produced in 315, Constantine is shown with the title of “Britannicus Maximus.” This conveys the idea of “Great Victor in Britain.” Constantine evidently fought a significant campaign in Britain and achieved a great victory there since nothing else would justify Constantine’s personal presence at such a delicate point in his career. Hence, we can conclude that there was likely a major rebellion in Britain at that time.

Did Eusebius Describe This Event?

It has been suggested that Eusebius referred to this forgotten invasion of Britain in his Vita Constantini. In three places, he refers to Constantine as subduing the Britons at or near the beginning of his reign. For example, in VC 1.25, he wrote:

“[Constantine] directed his attention to other quarters of the world, and first passed over to the British nations, which lie in the very bosom of the ocean. These he reduced to submission.”

While this sounds like it could be a reference to the campaign of 314, the surrounding context shows that this cannot be the case. After describing this event, Eusebius goes on to explain that Constantine subsequently campaigned against Maxentius. As we have already seen, that was in 312. Interestingly, other coins from London proclaim the advent of Constantine, which date from between 310-312. On this basis, it is evident that Constantine campaigned in Britain in that era, evidently putting down rebellions and gathering support in preparation for his war against Maxentius.

Hence, this passage from Eusebius cannot be in reference to Constantine’s campaign in Britain in 314. Another passage from Eusebius that might be relevant is from VC 4.50:

“Thus the Eastern Indians now submitted to his sway, as the Britons of the Western Ocean had done at the commencement of his reign.”

This refers to the Britons being subdued by Constantine at the commencement of his reign. While this could refer to the campaign of 314, there is no active reason to think that this is so. The same applies to a similar statement from Eusebius in VC 1.8. He could be referring to the event of 314, but there is no active support for this conclusion. Rather, the evidence from VC 1.25 suggests that Eusebius had in mind Constantine’s campaign among the Britons in c. 311 when he referred to him subduing them earlier in his reign. Therefore, it would appear that Eusebius probably did not know anything about this campaign of 314.

Does Constantine’s Invasion of Britain Appear in British Legends?

One medieval record might be a genuine reference to this event. This record is Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae, written in c. 1137. While much of Geoffrey’s account is famously unsubstantiated, scholars recognize that various parts of his account preserve authentic British traditions. The surprisingly accurate portrayal of King Cunobelinus from the 1st century CE is one example of this.

In Geoffrey’s account of Constantine’s departure from Britain to overthrow Maxentius, he describes how a leader named Octavius rebelled against the Romans in Britain. Octavius defeated the first Roman force that was sent against him. Sometime later, a second army was sent to put down Octavius’ rebellion, which was successful.

The account does not present a detailed timeline of events. Nevertheless, Constantine’s campaign in 314 would comfortably fit the campaign that Geoffrey presents as the second and ultimately successful campaign to put down Octavius’ rebellion. While there is no way of confirming this theory, it is not unreasonable to suggest that this may well be a genuine memory of Constantine’s otherwise forgotten invasion of Britain.

The Evidence for Constantine the Great’s Forgotten Invasion of Britain

In conclusion, we have seen that there is clear coinage evidence that Constantine the Great returned to Britain in 314. Given the perilous era in which this took place, this can only have been for a very good reason. The fact that he appears with the title “Britannicus Maximus” on coins minted the following year reveals the reason. Evidently, Constantine returned to Britain to put down a substantial rebellion. This occurred not long after he defeated Maxentius at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312.

However, it appears that his victory over this rebellion was essentially forgotten, and it has only recently been rediscovered. Despite suggestions that Eusebius noted it, the evidence for this is very weak. Arguably, the only trace of this event in surviving medieval records is found in Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Britanniae. His description of a major rebellion in Britain that began just after Constantine the Great left to fight Maxentius ties in well with the coinage evidence.