Personal perils of love, lust, and loss permeate the poetic repertoire of Cy Twombly. An abstract painter dabbling in experimentation, he pertains to a critical generation of American artists, sandwiched between Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art. His rhythmic lyricism has captured a cross-continental audience since his 1950s debut.

Cy Twombly’s Early Life

Born Edwin Parker Twombly in 1928, the artist had a quintessential all-American upbringing. His father worked as an athletic director, briefly pitched for the MLB, and established himself as a local Virginia personality. In fact, Twombly inherited his moniker from his father, nicknamed Cy Young after baseball legend Cyclone Young. Nevertheless, both Twombly’s parents hailed from New England, where he made frequent trips throughout his childhood.

Despite these ties to Massachusetts and Maine, his roots in Lexington firmly anchored his Southern identity long after he departed. His parents were also large proponents of his art career, nurturing his blossoming interest since youth. At age twelve, Twombly began studying under Catalan painter Pierre Daura, a modernist whose work fluctuates from abstract to figurative. This relationship proved incredibly instrumental. Alongside two other local artists, the pair would later be dubbed “The Rockbridge Group,” referencing shared inspiration from the nearby Blue Ridge Mountains.

Artistic Education

Cy Twombly spent his formative years slingshotting between various educational institutions. He began his formal training at The Boston MFA in 1947, and then spent another year studying at Washington and Lee University. By 1950, he had migrated to New York City to study at the Arts Student League, where he first met close confidant Robert Rauschenberg. While in New York, Twombly also took inspiration from the city’s founding fathers, mainly Jackson Pollock, Franz Kline, and Robert Motherwell.

Learning from this progressive vanguard, he developed an abstract vernacular unique to his early years in the United States. His monochromatic Min-OE (1951) best exemplifies this primitive attraction to symmetrical forms, expressive renderings derived from prehistoric Luristan bronzes. Twombly created this monumental painting while at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, where he enrolled at Rauschenberg’s behest in 1951. His prominent professors there would inevitably shape his artistic style.

While matriculated at Black Mountain College, Twombly started cocooning his creative metamorphosis. Only attending for a summer, he made connections to last a lifetime, including strengthening his relationship with Rauschenberg. Surrounded by strong voices like musician John Cage and poet Charles Olson, Twombly was also quite stimulated during these years, translating his dynamic ambiance onto his paintings.

His complete color erasure style emerges from this period, a practice many attribute to studying under Motherwell and Kline. Twombly also greatly admired Swiss symbolist Paul Klee, a radical who sought to illuminate action through brushstrokes. All produced works combining simple gestural techniques with iconography, which Twombly also replicated in his Myo (1951). Reducing painting to its mere essence, this densely-textured canvas became an autonomous subject, a self-referential nod to building blocks like form, color, and composition. Within the year, Twombly would come to celebrate his first successful solo-show in Chicago.

His First Solo Exhibition

The Seven Stairs Gallery hosted Cy Twombly’s first exhibition in November 1951. Organized by photographers Aaron Siskind and Noah Goldowsky, gallerist Stuart Brent presented paintings made during Twombly’s prolific 1951 rise to fame. Unfortunately, many of these are now lost or placed within private collections, notwithstanding his early abstract work Untitled (1951). Nevertheless, his show did garner significant critical attention, particularly from Twombly’s mentor Motherwell. “I believe Cy Twombly is the most accomplished young painter whose work I’ve encountered,” wrote Motherwell in relation to Twombly’s Chicago showcase. “Perhaps what is most remarkable of all is his native temperamental affinity with the abandon, the brutality, the irrational in avant-garde painting of the moment.”

From Pablo Picasso’s non-representational Cubism to Jean DuBuffetts decadent surfaces, Twombly surveyed art history’s very best for his heavy-handed allusions. Yet his sentimental work juxtaposed feverish motion with proportional harmony like never seen before.

His Travels with Robert Rauschenberg

In 1952, Twombly embarked on a journey to forever alter his trajectory. Awarded a substantial travel fellowship to broaden his artistic language, the painter invited Robert Rauschenberg to tag along on his eight-month escapade through Europe and Africa. From Palermo, the two reached Rome before proceeding to Florence, Siena, Venice, and eventually Morocco. Twombly developed new captivations during these brief cultural stints, particularly preoccupied with Etruscan relics and other ancient artifacts.

His later stop in Tangier would prove even more conducive to his creativity, however, evidenced throughout his prolific sketchbooks. These seemingly nonsensical scribbles now serve as a rough draft for Twombly’s dawning mature period, indexical blueprints of his expanding symbolic vocabulary. Later, he’d spend more time sketching African antiques at various ethnographic museums, cementing his interest in Greek and Roman mythology. Though his funds inevitably dwindled, Twombly’s international tour-de-force opened a figurative door to even wider spread success.

He Joined The Army

Cy Twombly joined the U.S. Army upon his return in 1953. Stationed in Georgia, he specialized in cryptography at Camp Gordon, crowding his days with intellectual puzzles and coded connotations. On weekends, he also rented rooms at local Augusta hotels to perfect his newfound compulsion with automatic drawing, an emerging Surrealist process. Foregrounding an artist’s subconscious, the arbitrary method exchanges mindful control for spontaneous freedom completed hastily.

Twombly’s take on the technique materialized in his unique biomorphic drawings, blind works completed in darkness. In his Untitled (1954), he veers toward broad cursive loops, wound into tongue-like knots to emphasize his fluid sleight of hand. Unlike automatic drawing, however, Twombly’s candid practice didn’t aim for a smooth flow. Rather, he began night drawing to artfully obstruct his own habitual dexterity, effectively rendering his work more childlike. Twombly himself even claimed Augusta solidified “the direction everything would take from then on.”

Cy Twombly’s Mature Period

By late 1954, Twombly had returned to Manhattan, settling into a tiny apartment on William Street. In New York, he also situated himself within an elite artist group, which included prominent Abstract Expressionist Jasper Johns. His new creations greatly differed from his American peers, though, if not due to his recent life-changing adventure. A large-scale series of grey-ground paintings synthesized Twombly’s desire to fuse energetic American sensibility with expressive European history.

While many remain only in photographs, one iteration, Panorama (1955) still exists today. Crayon and chalk on canvas, the 100 x 134-inch piece played on viewer optics through a striking light/dark contrast. It also marked the beginning of Twombly’s run-on handwriting, his now-signature scrawls. Around this time, the artist concurrently worked on a series of sand sculptures in Staten Island, all of which have unfortunately gone undocumented. New York’s Stable Gallery commemorated Twombly’s epochal efforts at a solo-exhibition in 1955.

Twombly took a leap of faith in 1957 when he permanently relocated to Rome. There, he also met his Italian wife Tatiana Franchetti, moved from property to property, and welcomed a son, Alessandro. He had introduced a lighter mood to his paintings by then, layering his allusions to Classical antiquity. In his Blue Room (1957), for example, vibrant yellow splashes dot an otherwise banal composition, his only work containing color during this period. In 1958, Twombly even sought to find new representation at the Leo Castelli Gallery, slated to showcase his first 1960 exhibition. Europe’s creative climate also acquainted him with famous poet Stéphane Mallarmé, shaping his poignant use of linguistic imagery. He drew Poems To The Sea (1959) while living in a small fishermen’s village between Rome and Naples. With innovative undertakings now on his horizon, a tranquil Mediterranean sea breeze subsumed what remained of Twombly’s scenic 1950s.

During the 1960s, Twombly’s modus operandi mutated onto grander surfaces, transfixed in delicate technicolor. From his studio in Piazza del Biscione, he populated his growing catalog raisonné with themes like eroticism, violence, and allegory. Rome’s architectural history also presented him with centuries of stimuli to respond to. By defining a mind-body duality, Twombly combined a simple, systematic approach to patterning with his impulsive nature-based pictograms.

Paintings like his frantic Ferragosto (1961) series represent this somatic retort to his environment, completed during Italy’s sweltering August holidays. In a fierce whirl of crayon, pencil, and paint, The Second Part of the Return from Parnassus (1961) also cites a Greek myth about Apollo and Muses, a focal point for mythological study. Others, like Death of Pompey (1962) convey a more literal analysis of gore, its pulpy surface seemingly smudged with blood. Twombly swerved further into metaphorical terrain as his European career crescendoed.

Cy Twombly’s Declining Fame

Twombly’s American fame declined as the decade continued. In 1963, he inaugurated his solo-show Nine Discourses on Commodus at the Leo Castelli Gallery, titled after a recently completed painting cycle. Gray backgrounds functioned as negative space to center impasto swirls of pigment, a reflection on President JFK’s recent assassination. Frantically paced, his thin-lined scribbles also simultaneously invoked and subverted his Abstract Expressionist contemporaries, then an already old-fashioned milieu.

While his works were well-received in Italy, his show earned vicious criticism from American audiences, many of whom had become distracted by Andy Warhol’s magnetic glitz and glamour. None of his paintings sold either, increasing Twombly’s rejected status as representative of old ideals. Later, during a 1966 Vogue photoshoot, opulent depictions of his Roman apartment spurred more media disapproval surrounding his luxurious lifestyle. Dissidents alleged Twombly had “somehow betrayed the cause.” Understandably, these condemning experiences calcified his aversion to publicity.

Cy Twombly consequently decreased his artistic output during the 1970s. Nevertheless, he split his time between Italy and his Bowery studio, celebrating international retrospectives in Turin, Paris, and Bern. Despite ongoing intellectual isolation from his craft, he also finished another series of moody grey-ground paintings earlier in the decade. In Untitled (1970), the largest of the batch, rows of sharply jotted coils unfurl freely through continuous forms, nostalgic of chalk on a blackboard.

Twombly’s unusual methodology involved standing on his friend’s shoulder to glide across the canvas. By the mid-1970s, he had also returned to sculpture after a near-twenty-year hiatus. Compiling, fragmenting, and assembling domestic-scale materials such as wood, twine, cardboard, and cloth, he subsequently washed them in white paint. Though rarely displayed, his trials ultimately set the stage for an expansive sculptural exploration later in life. Twombly toasted his sprawling achievements at a bountiful 1979 Whitney retrospective.

His Later Reputation

Public perception of Cy Twombly shifted in years to follow. Settling in seaside town Gaeta, he produced mixed-media deliberating his affection for the Mediterranean, slowly creeping back toward color. His four-part Hero and Leandro (1981) remain his most famous 1980s works, detailing a tragic narrative of love and death by drowning. Here, red droplets descend onto foamy green, white, and black waves, plunging directly into a visceral fantasy.

Twombly’s American audience also grew more receptive due to Neo-Expressionism, a movement favoring art’s redemptive power to be sensual, eloquent, and provocative. With forerunners like Jean-Michel Basquiat naming Twombly as a driving force, his 1990s met appreciable prosperity. While older paintings auctioned for millions, newer compositions, like Summer Madness (1990) tackled Italy’s changing seasons through vivid floral motifs. In 1994, MoMa documented his blowout retrospective by cataloging a cheeky essay: Your Kid Could Not Do This, and Other Reflections on Cy Twombly.

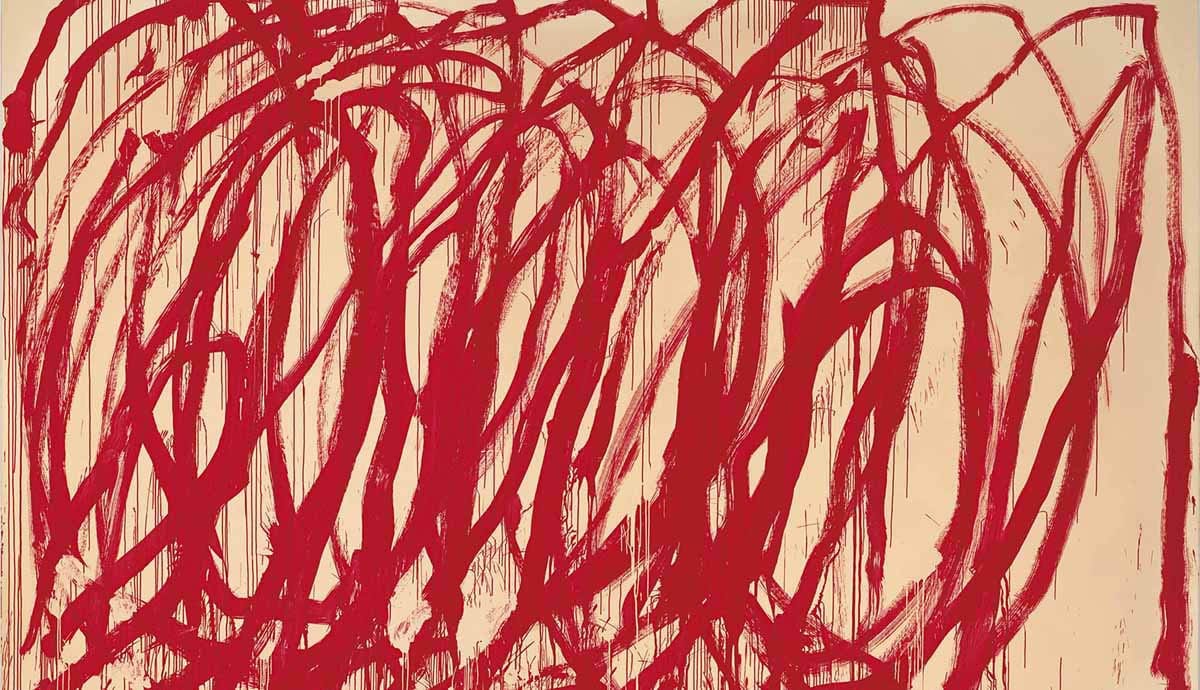

Cy Twombly lived his final years akin to his lengthy life: in constant oscillation. Between Caribbean summers, his New York reputation, and his Rome residency, his primary focus became sculpture and large-scale paintings. Compressing whimsy and ease, (Humpty Dumpty) (2004) revealed a meta-commentary on his fractured oeuvre, a timeworn relic of Twombly’s titanic legacy. His breakthroughs were celebrated at retrospectives in Basel, Tate Modern, and with a Golden Lion at the 49th Venice Biennale. Twombly also turned his attention toward the hedonistic Roman god of wine, Bacchus, to whom he dedicated multiple later works. Untitled (2005) is perhaps his most popular, where an illegible red delineation of the term “Baccus” spans a towering, ten-foot canvas. Hidden traces of Twombly’s psyche are amplified throughout his final paintings, which were displayed in an tragicomic Gagosian exhibition following his death in 2011. Bright, bubbly, and botanical, Camino Real (2011) signaled his last-completed series.

Cy Twombly’s Legacy

Cy Twombly continues to break headlines posthumously. Whether deep-dives into his contested sexuality, scandals regarding a supposed assistant, or record sale numbers, the incendiary looms like a mythic figure over American art history. Nuanced emotions unite his mixed-media work through high and low brow materials alike, even as his chameleon complexities advanced. Within his deeply intimate calligraphy, however, lies a keener reflection of an evolving society who consumed, shaped, and diminished it. By synthesizing poignant linguistic puzzles into accessible imagery for viewers to dissect, Twombly converted his own internal imbalances into digestible tidbits of humanity, everlasting vestiges of his mighty presence.

As contexts change, so do our efforts to understand his irregular interpretations, to transfix our own narratives as Twombly once did. Luckily, he’s bestowed plenty of source material for the foreseeable future. Our infinite imaginations will always beckon renewed appreciation for Cy Twombly.