Dating back to ancient India, music has always been considered to be of divine origin in the differing philosophical clusters of Hinduism. Religious worship is usually exceptionally musical, charged with the sounds of mantras, songs, recitations, and prayers. This invariably influences the faculty of dance. From the cosmic dance of Lord Shiva, the Nataraja, to the divine erotic Rasilas of Lord Krishna, Dance expresses significant devotion to the Gods in Hinduism. The Gods are fierce dancers themselves, while their mortal devotees dance in turn for their love and adoration.

The Dances of the Hindu Gods and their Devotees

Sages in India have long since been the chanters of the Vedas, and accompanying that, the art of dance has permeated society.

The earliest example of dance in Hindu texts is from the Natyashastra of Bharata. It is dated between 500 BCE and 500 CE. The text is a definitive treatise and manual for the performing arts, such as music, acting, and, most importantly, dance. It is a complex systemization of the aesthetics of performance, which can be remarkably insightful and spiritual.

The Natyashastra presents dance (and aesthetics in general) as closely intertwined with the mythology of Hindu devas and devis, that is, deities. Because of this, the rules and philosophical order of the aesthetics of dance are inextricably linked with myths, making performance a Vedic ritual. In order for dance to fulfill its role in ritual ceremonies, it has to successfully evoke the Rasa, which literally means nectar or essence.

The Rasa theory states that spiritual happiness is innate in every human being. However, Rasa can be obstructed, or be difficult to access from within. A great performance can evoke this Rasa in the dancer (or performer) and in the audience. It is imperative to discover this Rasa, in order to find a transcendental plane of existence. This transcendental plane comes from devotional expression through practice (dance), similar to reaching Nirvana in Buddhism.

Most significantly, this Rasa is evoked in a manner that represents the divine, the human, and the demonic. This tri-concept view of cosmology and aesthetics is the basis of spirituality in Hindu dance because of the corresponding Trimurti (Trinity) of supreme divinity in Hinduism.

The Trimurti, as is mirrored in the Rasa theory, represents creation, preservation, and destruction. Lord Brahma is the creator, Vishnu the preserver, and Shiva the destroyer. Out of the three, Shiva is often depicted as the dancing god, the Nataraja.

Shiva, the Nataraja: Dancer of the Cosmos

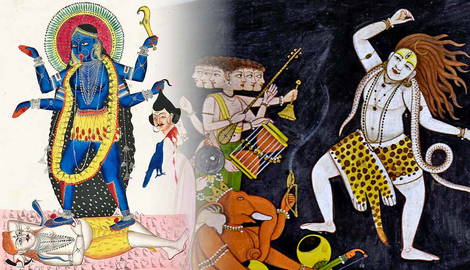

Shiva is one of the most mesmerizing of the Gods. His avatar, Nataraja, “the king of the dancers,” is teeming with esoteric symbolism. Snakes coil around his arms and neck; his arms multiply from two, to four, to ten; a trampled demonic Muyalaka beneath him; a fiery arch surrounds him; he wears the moon and the river Ganges in his hair, while clothed in the skins of tigers and elephants; his body is covered in ashes from funeral pyres with a drum in one hand and fire in another. He is dancing! Dancing in the hills of the Himalayas, dancing on burning grounds, in cemeteries. He also dances in the center of the universe, the Chidambaram.

The image of a dancing Shiva is the culmination of many aspects of Hindu spirituality and divinity, all combined into one grand representation. In Tirukuttu Darshana (Vision of the Sacred Dance), the ninth tantra of Tirumular’s Tirumantra, a Tamil poetic work of the 6th or 10th CE, describes this image as:

“His form is everywhere: all-pervading in His Shiva-Shakti, Chidambaram is everywhere, everywhere His dance: As Shiva is all and omnipresent, Everywhere is Shiva’s gracious dance made manifest…Our Lord dances His eternal dance…He dances in our body as the congregation.”

(Quoted in Coomaraswamy, 1957)

Shiva’s dance is powerful and fierce. His dance consumes and protects, destroys, and creates. Time is still, yet the dance and the primordial God is eternal. Shiva’s dance manifests an enraptured infinity.

In The Dance of Shiva (1957), Coomaraswamy, the renowned philosopher-metaphysician, argues that the performance has a threefold significance. Firstly, the rhythmic play of the dance is the source and the mirror of the movement of the Cosmos. This is represented in the burning arch that encircles the God. Secondly and enigmatically, the dance releases the people ensnared in worldly Illusion. And lastly, the place of the major divine dance is at the center of the universe, which is within the heart.

This threefold significance encapsulates the essence of the Trimurti because it represents cosmic cycles. Shiva creates, but he also destroys; that’s why he dances in the center of the universe, but also amongst the ashes of the dead.

Shiva’s dances, Tandava, are of two types: Ananda Tandava, performed with joy; and Rudra Tandava, performed in anger. This represents all-encompassing creation, preservation, and the dissolution of the soul and the world in one grand performance. All of this symbolizes the idea that destruction is, at the same time, creation.

The universe’s dynamic nature is manifested through the dance of the Gods. In a story concerning the Nataraja, the goddess Kali is said to be a fierce, ruinous aspect of Parvati, Shiva’s consort. Kali, in a dire moment, embodying the wrathful divine feminine, is said to have emerged from Shiva’s third eye when he was enraged by the demon Raktabija. Kali was so powerful that she was able to slay Raktabija, but her rage was uncontrollable. She began the dance of destruction, razing everything, even the Gods themselves. Seeing this, Shiva lay down on the ground and allowed Kali to dance and trample on his chest.

The dance of Kali and Shiva embodies two polarities of the universe: Shiva is the male principle of creation and destruction, while Kali is the female principle of energy and transformation. For renewal, destruction is necessary, and dance renders this dynamic most effectively.

Krishna’s Raslila: The Dance of Divine Love

Another one of the Gods’ great performances in the Hindu tradition is Krishna’s Raslila. The Rasilas have an erotic element to them as Krisha is joined by the Gopis, the milkmaids, as they dance, sing, and chant. The word Ras means “nectar,” “essence,” or “taste,” and Lila means “play” or “sport.” Thus, Raslila can be called the dance of divine love. It evokes a powerful sense of passion and a celebration of youthful joy. The playful words that make up the compound Raslila create an image of luxuriant, pleasurable recreation.

In the sacred Hindu texts, Krishna has been characterized as a beautiful, flute-playing blue warrior. Along with this, a more popular and endearing depiction of him is as a playful and young God-child who loves to eat laddus, a common sweet in India. So, the Rasila is by design quite different from the fierce cosmic dance of Shiva and the fatalistic dance of Kali. It is more light-hearted.

The Raslila takes place in the depths of the forest of Vrindavan, where Krishna grew up. The story of the Raslila goes like this: One night, Krishna plays his delightful flute music, as he frequently did. The music drew the Gopis to the forest, where they began to dance with him. The dance was so beautiful and intoxicating that the Gopis forgot everything else, including their families and their homes. They danced all night long, lost in the bliss of Krishna’s love.

Unlike the destructive renewal of Shiva and even Kali’s dances, Krishna’s Raslila provokes a quality of bliss. There is endearing Ananda, “happiness,” in the performance of the Raslila. The young Gopis and the God Krishna symbolize a passionate freshness in the way they mingle and dance. Gopis use their bodies and souls for worship amongst the natural forestry of Vrindavan. The Raslila renders an image of the divine love between Krishna and the Gopis. It is also a symbol of the soul’s journey to union with God. The Gopis represent the individual soul, and Krishna represents God, as the dance is performed in a circle, with Krishna in the center, as the God-performer.

The Bhakti Movement and Devotional Expression

Now that we have seen some of the most influential Gods dancing their way around the universe, through evil and within the depths of the forest, we can shift our focus to the dance of mortals.

A major turn in the history of Hinduism was the Bhakti movement. Beginning in the 7th century, the movement stretched far and lasted successfully until the 18th century CE. The movement originated in South India, and it spread to North India in the 12th century CE. This was an important movement for the religious development of Hinduism.

The movement emphasized Bhakti, meaning “devotion,” to a personal god or goddess as the ultimate path to salvation. The central point of faith became devotion through different ways and skills.

The Bhakti movement was led by a number of saints and poets who composed songs and poems in praise of the gods and goddesses. Art became significant both to the movement and to the idea of devotion itself. These songs and poems were often written in local languages, which made them accessible to a wider audience, and also meant everyone took part in Bhakti.

One of the most significant of the devotional expressions encouraged during this time came in the form of dance. The yantra “instrument,” in dance, became an expression of the body-mind-soul connection, which was in itself seen as worship. Many of these dances are performed in temples as a form of reverence.

The 8 Classical Dances in Hindu Spirituality

The study of the Natyashastra became even more widely read during and after the Bhakti movement because it laid out the aesthetic roots of dance. This led to the blossoming of the eight classical dances: Bharatanatyam, Kathakali, Kathak, Kuchipudi, Odissi, Sattriya, Manipuri, and Mohiniyattam. As explained, the dance must evoke a Rasa, a beautiful elemental emotion in the viewer and sometimes the dancer themselves. A performer can incite this by invoking a particular bhava, “gesture of facial expression,” which is essential to Rasa theory.

There is immense variety in the different disciplines of dance. Of all the classical dances, Bharatanatyam remains the most well-known and popular classical dance form in Hinduism. It is also popular outside of the Subcontinent due to the rise in cultural exchange through dance and other types of art.

Bharatanatyam dates back to 1000 BC, coming from the Tamil Nadu region in South India. The Carnatic music accompanying the devotional dances is deeply poignant and forceful, usually concerning the Gods and Goddesses of the Hindu tradition.

Kathakali, on the other hand, is from the Indian region of Kerala, and it incorporates elaborate makeup and costumes, along with a dramatic aspect to the dance. Most Kathakali dancers are also singers as well.

Kathakali is quite different from Kathak, which originated in Northern India through the traveling poets and storytellers called “Kathakars.” Odissi, another type of classical dance, began in the Hindu temples of Odisha, disseminating devotionals to the Gods.

All these different types of dances are forms of devotion through performance in Hinduism. The lingering, intense quality of the performance is a rendition of religious love. The rich sacred texts of ancient India show the Gods performing with the same vigor and strength as the classical dancers, creating a portal to divine union that allows mortals to connect with the divine.