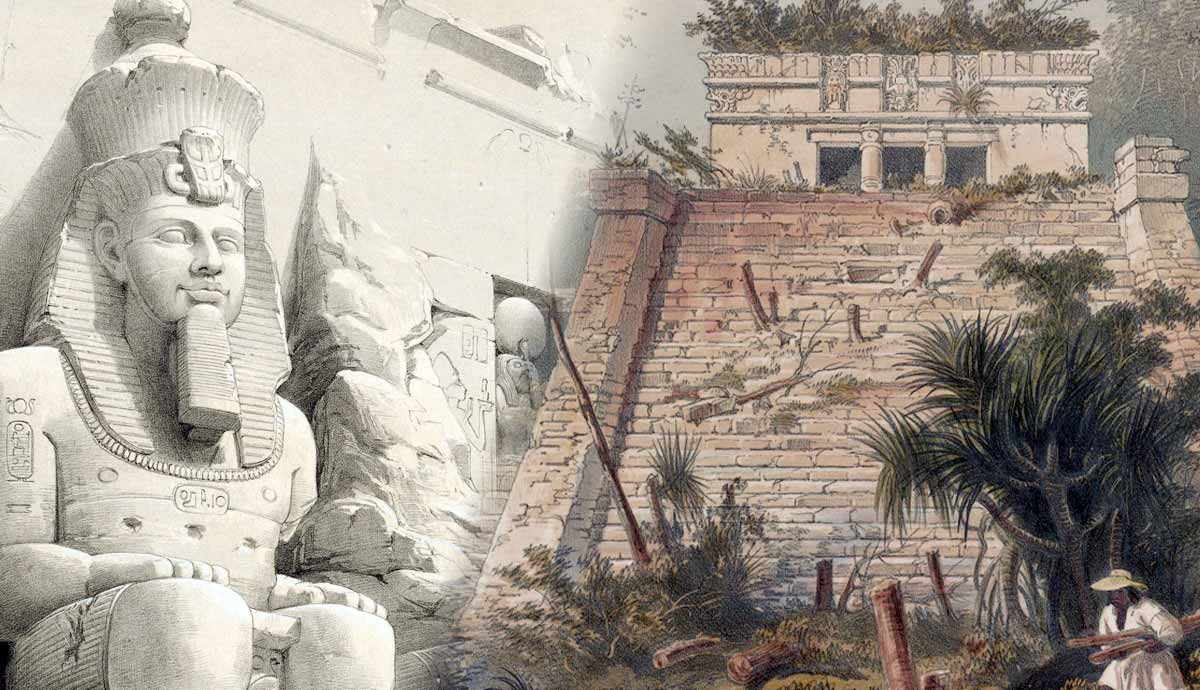

In the space of four years during the twilight of the 18th century, four noteworthy events with no apparent connection took place. In 1796, David Roberts was born in Scotland. In the same year, Alois Senefelder invented lithography in Germany. In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt, and in 1799, Frederick Catherwood was born in England. As time passed, fate conspired to bring these disparate occurrences together. Their coalescence would contribute to a monumental upsurge in the public interest and scholarly knowledge of two of humanity’s most impressive and enduring ancient civilizations, the ancient Egyptians and the Maya.

Historical Background – Expansion and Exploration

At the dawn of the 19th century, against the backdrop of the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802), European powers like Britain and France engaged in a flurry of surveying and mapmaking. As part of their scramble to outdo each other in the pursuit of conquest and colonization, they planned and carried out massive investigative projects. Their aim was to record and chart as much as they could of foreign lands. This activity sometimes included documenting and depicting their cultures and heritage.

A few years before Britain commenced the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India in 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Egypt (1798), which was still part of the Ottoman Empire. He knew that gaining control of the country would be an important strategic triumph in his war against Britain, providing him with easier access to the East. After a three-year battle against the British, Ottomans, and Egypt’s ruling Mamluks, Napoleon’s military endeavor ended in defeat. However, the campaign would result in a success of another kind, one of great academic and artistic merit.

A Grand Description of Egypt

As part of his retinue, Napoleon took with him 150 experts whose task was to seek out and record Egypt’s past and present. Their fields of study ranged from history, cartography, and art to science, engineering, and architecture. After their finished work was combined and collated, it was published over the course of two decades (from 1809) in a series of seminal volumes called Description de l’Égypte. This behemoth of 19th-century printing was the first scholarly step along the road to rediscovering the magnificence of a civilization that was, until then, still largely unknown to most Europeans.

Raiders, Romanticists, and Realists

The illustrations and engravings that featured in the Description de l’Égypte helped fuel a fascination with all things Egyptian and inspired more people to visit. Some, like Jean-François Champollion, were serious scholars, while others acted more like treasure hunters, damaging sites and carrying off antiquities to European museums. Egypt’s biblical connections and exotic allure compelled artists to reproduce the mysterious ancient inscriptions and sketch scenes of local life. Such material was perfect subject matter for the adepts of Romanticism and Orientalism, movements that reached their peaks during the 19th century.

During this period, artists produced lavish, spectacular pieces that catered to the burgeoning Orientalist sentiments of the day. Their work was often highly detailed but lacked authenticity, being compromised by Western bias and liberal use of stereotyping. Sketches and paintings of life in Egypt and other Middle Eastern countries included a combination of real-world and fantasy elements, resulting in evocative and impactful pieces that were not particularly accurate. Many artists gave preference to depictions of modern life over the colossal temples and monuments of the pharaohs. Some didn’t even visit the places they depicted, forgoing firsthand travel and instead using their imaginations, mismatched props, and the accounts of others to produce their works.

A few artists did attempt to focus on Egypt’s ancient ruins rather than using them as mere decorative backgrounds to complement the human subjects that usually took the main stage. Although their works acted as a window through which outsiders could catch a glimpse of Egypt’s past splendor, quality varied, and depictions were often quite basic. It would not be until the visit of a professional painter from Edinburgh that the remarkable nature of the monuments would be represented with the attention to detail they deserved.

David Roberts – Scottish Painter

David Roberts (1796-1864) was a landscape, townscape, and Orientalist painter. He developed his craft as a stage scenery artist and produced drawings, watercolor sketches, and oil paintings throughout his career. Although some of his work shows a flair for the dramatic, the higher degree of accuracy he strived for set him apart from most of his Orientalist contemporaries. Roberts was also a keen traveler, making sure to go and see his subject matter in person. This habit would help him make more faithful and realistic reproductions of ancient Egyptian architecture and monuments. He had already made trips to other foreign countries, such as France, Spain, and Morocco before he undertook his most famous journey.

In August 1838, Roberts embarked on an eleven-month tour of Egypt and the “Holy Land.” In the same year, he was elected Associate Member of the Royal Academy, and his new project would cement his position and reputation as a first-class artist. Though aware that the rising interest in the region’s history and culture presented a commercial opportunity, he could hardly have anticipated just how successful his adventure would turn out.

Travels in Egypt and Nubia

Travel in the 1800s was far from easy. After spending several weeks making his way to Alexandria, Roberts had to deal with the incredible heat and ever-present threat of disease. In 1835, just three years before he arrived in the country, an outbreak of bubonic plague had decimated the population of Cairo. Undeterred, the painter continued southwards up the Nile and started his work. Covering hundreds of miles of arid terrain, he visited sites that had also fallen victim to the ravages of nature over the centuries. Desert sand piled up against time-worn stone statues and temples, hinting at the grandeur of a long-forgotten power. Roberts’ awe-inspiring depictions of Egypt’s ancient architecture in that forlorn condition have a unique atmosphere and an almost tangible quality about them.

During his wanderings throughout Egypt and the Middle East, Roberts’ artistic output was prodigious. He didn’t limit himself to ancient ruins; he also sketched and recorded the region’s landscapes, religious buildings, and people. Examples from his portfolio that show ancient monuments are especially significant because of the lengths he went to display their finer details. The intricacy of the hieroglyphs he included in his representations of Egyptian temple columns, obelisks, and other monoliths reveals his efforts and talent.

Roberts’ more grounded and meticulous approach to rendering such wondrous sights did not mean that he was completely unaffected by a romantic aesthetic perspective. He sometimes made minor adjustments to his subjects’ positioning and scale to create an even more spectacular version of the things he observed and illustrated. Despite these minor compositional alterations, his work shows a high level of accuracy. Moreover, the quality of the images he produced during his tour of 1838-39 was unmatched by anything that preceded them.

Return and Publication

After almost a year of travel that also included visits to other historical sites outside Egypt (including Petra, Jerusalem, and Baalbec), Roberts returned home. He had amassed a huge collection of artwork, and his next task was to get it published. From 1842-49, he worked with master lithographer Louis Haghe to transform his drawings into plates. The versatile printmaking technique of lithography, which was still relatively new and advanced, enabled Roberts to reproduce his work in larger volumes. His sketches and watercolors would also benefit from Haghe’s technical skill and nuanced application of shade and tone adjustment.

Although the enterprise was expensive (Roberts had to secure funding by advanced subscription), the two artisans collaborated to produce a six-volume masterpiece. Initially published separately as The Holy Land and Egypt and Nubia, the luxurious travelogue featured 247 high-quality lithographs based on Roberts’ drawings. Britain had never seen such a prolific and accurate representation of the land of the pharaohs. Queen Victoria had been Roberts’ first subscriber, and after others had followed, the Egyptomania that gripped the nation intensified.

From the pyramids of Giza to the temples of Luxor and Aswan, Roberts had succeeded in recording and sharing the magnificence of ancient Egypt’s architectural treasures in exciting new detail. Because some of the sites he cataloged would later be damaged, destroyed, or removed, his artwork would also become a valuable archaeological reference over time.

From the “Old World” to the “New World”

“All was mystery, dark, impenetrable mystery, and every circumstance increased it. In Egypt the colossal skeletons of gigantic temples stand in the unwatered sands in all the nakedness of desolation; here an immense forest shrouded the ruins, hiding them from sight, heightening the impression and moral effect, and giving an intensity and almost wildness to the interest.”

(John Lloyd Stephens, 1841, p. 105)

In the first half of the 19th century, the history and culture of the Maya were even more mysterious than those of the ancient Egyptians. King Charles IV of Spain had instigated an antiquarian survey of Mesoamerica that included some Maya sites (1805-08), but it would take decades before scholars began to understand them. Explorers and artists from a wide range of backgrounds visited the ruins, trying to comprehend the strange structures that peered out through the dense jungle vegetation. Many refused to consider the possibility that the striking architecture and complex designs could be the work of indigenous peoples. Instead, they theorized that the buildings and monuments must have a connection to the civilizations they were more familiar with.

Some people suggested Greek or Roman influence. Artist Jean-Frédéric Maximilien de Waldeck produced images that included fabricated features like elephant heads and the cross-armed postures of ancient Egyptian statuary. Misinterpretations and embellishments like these (that sometimes even touched on the myth of Atlantis) exemplified a failure to decipher the evidence. The complicated and stylized art of the Maya made it very difficult to discern and identify, which exacerbated early artists’ tendencies to veer away from objectivity. It would take a more rational study of the vestiges of the civilization spread across Central America, Chiapas, and the Yucatán Peninsula to get closer to the truth.

Frederick Catherwood – English Artist and Architect

The man responsible for the timeless engravings and lithographs that helped lift the veil of ignorance covering the Maya is almost as enigmatic as the structures he recorded. His name was Frederick Catherwood. Unlike Roberts, there are no photographs or confirmed portraits of him. He was born in Hoxton (London) and established himself as an architect, draftsman, and traveler. He visited the Middle East before Roberts, but he is most well known for his exquisite depictions of the art and architecture of the ancient Maya.

Catherwood seems to have had a voracious appetite for travel to parts of the world with ancient architecture. During the 1820s and 1830s, he had journeyed to Rome, Greece, and the “Holy Land.” He had also been to Egypt twice. The studies and sketches he made of the remnants of ancient cultures that dotted those lands would stand him in excellent stead. Although many of his drawings remain unpublished, some of the work he undertook in the humid jungles of Central America and present-day Mexico would be. Catherwood’s illuminating illustrations constituted an essential element of John Lloyd Stephens’ groundbreaking archaeological travel books.

Travels in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatán

After first meeting in London, Stephens and Catherwood formed a partnership based on their mutual interests in travel and antiquity that led them on trailblazing expeditions together. Their scientific approach to research, which rejected the implausible theories of earlier explorers, made them pioneers of Mesoamerican archaeology. Stephens recounted the pair’s adventures and presented their discoveries in his insightful travelogues. Incidents of travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1841) and Incidents of travel in Yucatan (1843) are exciting reads and proved very popular upon release. Not only did they sell well, but they also shone a light on the politics, society, and history of the places the scholarly companions visited.

Stephens and Catherwood commenced their initial expedition in 1839 during a time of civil war. The circumstances and conditions under which they worked were dreadful. They were assaulted by tropical downpours and under constant attack from biting, disease-carrying insects. They both contracted malaria, and Catherwood became so ill that the pair had to bring their first trip to an early close the following year. However, they would return to the region and, despite the challenges, managed to visit more than 40 sites. Their determination and fortitude enabled them to study ruins of enormous archaeological importance, such as Copán, Quiriguá, Palenque, Uxmal, and Chichén Itzá.

During their journeys, the two friends documented and recorded the architecture and monuments they came across with great stoicism and skill. Catherwood’s meticulous drawings show the keen eye and technical precision of a professional draftsman. In order to enhance the accuracy with which he already worked, he employed a device called a camera lucida. With this, Catherwood was able to superimpose an image of a subject onto his drawing surface. The method helped him better ascertain the correct proportions of the objects and structures he cataloged for Stephen’s influential publications.

Catherwood’s Contributions

History has given much more attention to the writer of the Incidents of Travel books than to the man who illustrated them. Although Stephens is usually credited with “rediscovering” the ancient Maya, it was Catherwood’s drawings that provided the public with a tantalizing visual insight into the legacy they left behind. In total, more than 200 of his engravings are featured in Stephens’ volumes. In addition to his architectural drawings, Catherwood also attempted detailed reproductions of the confusing Maya glyphs. His renderings of the symbols were not perfect, but at the time, they were the most faithful portrayals anyone had created.

It wasn’t just the draftsman’s ability to draw the baffling artifacts and carvings that defined his contribution to the study of the Maya. His previous travel and work experience bolstered objective reasoning that was essential to recognizing that the remains he came across were indigenous. After his firsthand studies of the ancient art and architecture of other lands, Catherwood had seen enough to believe that those he sketched in Mesoamerica were unrelated. Time would prove him correct.

Even though it was the most widely viewed, the collection of engravings that Catherwood supplied for the Incidents of Travel series was not his ultimate work on the Maya. In 1844, he published his own book, Views of Ancient Monuments in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan. For his magnum opus, Catherwood worked with several lithographers to produce 26 plates that are of higher quality than those included with Stephens’ accounts. The color and vibrancy of the lithographs accentuate the details Catherwood captured and show the dramatic lighting he used to convey the atmosphere of the mysterious, neglected ruins he visited.

Roberts and Catherwood – Two Artistic Giants of Antiquity

Through their tenacious dedication and skill, David Roberts and Frederick Catherwood played crucial roles in educating the public about the history, culture, and architecture of the ancient Egyptians and Maya. Their accurate and realistic representations of the stupendous sites and monuments they recorded also contributed to the advancement of archaeological and ethnographic studies.

Roberts and Catherwood emerged as artists at a time when Europe was fascinated with the ancient world. The quality and beauty of their pieces added to the frenzy that Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt started. However, the precision and discernment with which they worked also introduced a grounding factor. Their art helped to dispel incorrect interpretations and offered an alternative to the stereotypical Eurocentric images and ideas that were en vogue.

By utilizing the best printmaking technology of the day, they each created exceptional lithographs from their drawings and paintings that have as much power to inspire now as they did in the 1840s. It was not long after that the new invention of photography superseded the work of painters and draftsmen. In spite of that, one may argue that the images the two adventurous artists produced are even more impressive and timeless than those that others captured later.