Attitudes towards death in ancient Rome were complex and not confined to one particular viewpoint. This vast topic covers everything from beliefs about life after death to funerary practices and commemoration of the deceased. In examining this subject, we must also consider external influences, such as that of ancient Greek culture, and how beliefs and trends changed and developed over time. Death in ancient Rome is, therefore, a diverse and fascinating topic and one which can provide some important insights into Roman civilization.

Death And Society In Ancient Rome

An exploration of the relationship between Romans and death can tell us as much about the living as about the dead. Death and the funerary process which surrounded it was often an opportunity for a display of social status, not just for the deceased but also for their family. Funerals served as poignant reminders of past ancestors and also of the descendants to come. Monuments to death, such as tombs and epitaphs, were important permanent memorials for both the dead and the living within every section of Roman society.

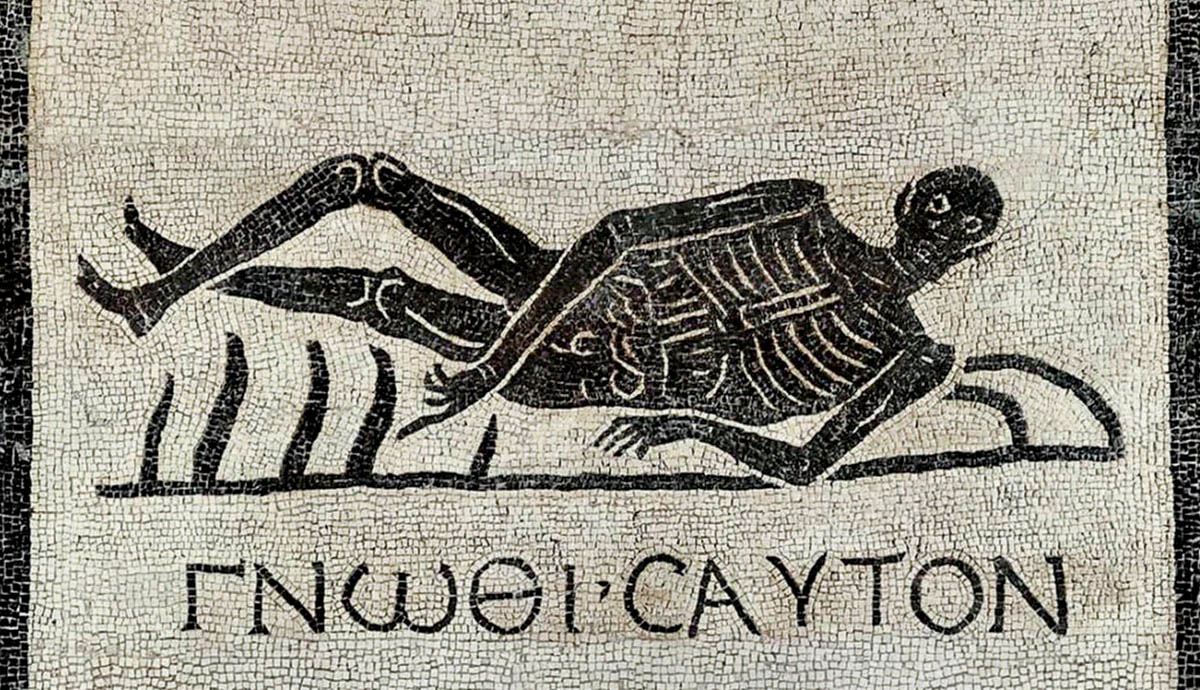

From the artifacts left to us today, we can get an idea of the role death played in daily life in ancient Rome. Some Romans were highly superstitious and went to great lengths to avoid any association with death. Others appear to have surrounded themselves with representations of death, such as skeleton figurines and skull mosaics. These representations have been interpreted as reminders of the transience of life and the importance of living life well.

Death was, of course, a subject that appeared regularly in Roman philosophy and poetry. The poet Horace was an enthusiastic advocate of using death to make the most of life. He left us with many sayings that are still well known today such as ‘carpe diem’ (seize the day).

Beliefs About Life After Death In Ancient Rome

There were no fixed or enforced beliefs about life after death in ancient Rome. The general consensus was that the deceased lived on in the Underworld. Influences and adaptations from Greek culture can be found throughout Roman poetry, such as The Aeneid by Virgil. In this epic poem, the hero Aeneas ventures into an Underworld that reflects the Greek equivalent, Hades. Here Aeneas encounters the dream-like Fields of Elysium, where the souls of the blessed reside, and gloomy Tartarus, the home of the damned. The unburied wait restlessly on the shores of the River Styx. It was believed that their souls haunted the living.

Gods associated with the Underworld, such as Pluto, Persephone, and Mercury, were worshiped widely, particularly in times of personal crisis. The Di Manes were believed to be the spirits or minor deities of the Underworld and the dead were thought to join their ranks in the afterlife.

There were even dedicated festivals at which the souls of the departed were celebrated. The Di Manes were worshiped at the Parentalia, held from the 13th to 21st February each year, as well as on the days of birth and death of the deceased. Even the unburied had a festival, every May their souls were appeased during the Lemuria.

The dead also lived on, in the domestic and public sphere, through imagery. In Roman households, particularly aristocratic ones, there was a practice of creating molded masks from the faces of family members. Some masks were even made after someone had died. The masks were then kept in the family throughout the generations and often displayed in the main hall of the house. At family funeral processions the masks of ancestors were worn by current family members as a way of preserving their memory.

Life after death in ancient Rome was quite different for emperors. After his assassination in 44 BC, Julius Caesar became the first Roman mortal to be deified after death. In a process known as apotheosis, many emperors who followed were also elevated to the status of a god after death. There were some, such as Emperor Caligula and Emperor Commodus, who even insisted on being deified while they were still alive. But most emperors, including Emperor Augustus, actively rejected deification during their lifetimes.

Funerary Practices In Ancient Rome

Death in ancient Rome was thought to be something that could infect or be harmful to the living. Therefore there was a strict physical separation between the living and the dead. A boundary existed around inhabited areas, known as the pomerium, and it was only outside this boundary that the dead could be buried. Beyond the pomerium, it would have been common for travelers to have seen tombs lining the main roads into and out of cities and towns.

This sense of separation also extended to family members of the deceased during the funeral period, which lasted for eight days. During this time the family would isolate themselves from the community and only re-entered society after the funeral was complete. Cypress branches were often hung outside the houses of those affected.

There are similarities between funeral services in ancient Rome and services in some cultures today. A eulogy would often be read by a family member at the graveside, for example. Close relatives had specific duties such as physically closing the eyes and mouth of the deceased. For cremations, it was the role of a family member to light the pyre and collect and clean the bones afterward.

Customs concerning death in ancient Rome varied over time and this was particularly true of burial practices. The earliest Roman graves to have been discovered date from the 10th century BC and they include both urn cremations and burials. Neither cremations nor burials appear to be restricted to any particular time period or social group.

In the Late Republican era, the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, cremation appears to have been the most common practice. Urns were filled with the ashes of the deceased and then placed inside elaborate family tombs. The less wealthy used a communal columbarium which was a brick structure with numerous niches for the funerary urns.

By the 2nd and 3rd centuries, AD burial had become popular again, coinciding with the rise of early Christianity which favored burial. As in many cultures, wealthy citizens were buried with grave goods such as fine ceramics and precious jewelry.

Tombs And Epitaph Inscriptions

The commemoration of a person’s life and death in ancient Rome was often made through tombs and epitaph inscriptions. These memorials were employed by all members of Roman society from slaves to emperors.

Many Romans believed that immortality came from a person’s presence living on in the hearts and minds of those they left behind. The permanence of stone tombs and inscribed epitaphs reinforced this idea of prolonging the memory of life after death.

Maintenance of tombs was a very important duty for family members and freedmen and freedwomen of the deceased. On days of birth and death, the family would celebrate funerary rites at the location of the tomb. Libations were poured into the ground and food was left as an acknowledgment that the dead lived on in another realm.

The origin of the inscribed Roman epitaph dates back to the earliest Greek stelae, or grave markers, of the 7th century BC. Greek and Roman epitaphs normally used very formulaic language but they were also full of personal information, albeit in an abbreviated form. The inscription would commonly consist of the following: an invocation of the Di Manes; the name of the dedicator, the name of dedicatee and relationship between the two; job and career highlights; age at the time of death and sometimes the descendants’ responsibilities with regard to the tomb.

Some of the most interesting epitaphs increased their impact by speaking out to onlookers and encouraging them to read their inscriptions. Forms of address such as viator (traveler) or hospes (guest) were common ways of engaging their audience. These speaking tombs attempted to prolong the memory of the dead by establishing a connection with the living.

Epitaphs and monuments to death in ancient Rome took many different forms and styles. The style of epitaph is normally a good indicator of a person’s social status. The above dedication is to Marcus Ulpius Urbanus, a freedman of the imperial household who became an assistant goldsmith. The lettering used is neat, uniform and well-spaced indicating that this inscription would have been expensive to produce. The inscription tells us that the tomb on which it was found was commissioned by Urbanus himself and his wife. The choice of an elegant and formal inscription is therefore a reflection of how Urbanus and his family wished to be seen by society.

The above epitaph inscription is to Gnome, who was a slave-girl and hairdresser to a woman called Pieris. Both Gnome and Pieris have names of Greek origin. Many slaves in ancient Rome came from Greece, it is likely therefore that Gnome’s mistress, Pieris, was an ex-slave. The lettering of this inscription is far more rudimentary and informal than that of Urbanus. This epitaph would have been quite cheap to produce and is reflective of Gnome’s slave status.

Fascinating Monuments To Death In Ancient Rome

Some monuments to death in ancient Rome displayed wealth and social status on a very grand scale. One exceptional example of this is the tomb of Eurysaces in Rome, much of which is still standing today. The inscriptions tell us that Eurysaces was a baker and a bread contractor. The enormous tomb stands 33 feet high and is decorated with an elaborate frieze that depicts the various stages of bread making. Large circular niches fill one entire side of the tomb and some scholars have suggested that these resemble bread ovens.

The size and decoration of the tomb indicate that life after death was important to Eurysaces. He clearly wanted the world to continue to remember his name long after he himself had gone. Many scholars assume that Eurysaces was a very wealthy freedman due to his ostentatious style.

However, vast tombs were not just the preserve of the Roman nouveaux riches. The Appian Way is one of the main arteries of Rome. Many tombs and mausolea line the route and can still be visited today. One of the most fascinating examples is the Republican mausoleum of Caecilia Metella. This huge structure commemorates the life and death of the wife of Marcus Licinius Crassus, the son of the infamous triumvir Marcus Crassus. The mausoleum is better described as a small castle due to its tower and battlements. It was even used as a fortress in medieval times.

Unlike Eurysaces’ tomb, it is difficult to say how much of this tomb reflects who Caecilia Metella really was. The war-like structure does not appear to be synonymous with an elite Roman lady. It is far more likely that this was meant as a display of family nobility and superiority.

The vast subject of death in ancient Rome can, therefore, tell us as much about the living as it can about the dead. Beliefs about life after death as well as the commemoration of the dead were perhaps most important for those left behind. These beliefs and practices were an opportunity for comfort in grief as well as for a display of social status.

Ancient tombs and epitaphs have also successfully allowed the memory of the departed to live on to this day. It is because of these permanent memorials that we are still aware of Eurysaces the baker, Gnome the hairdresser, and many thousands more.