Considered Egypt’s Golden Age, the New Kingdom was a period of economic success, expansion, and advancements in technology, art, and architecture. Some of ancient Egypt’s most spectacular monuments date from this era. Unfortunately, this mighty empire fell into decline, like many civilizations did during the Late Bronze Age. Several factors contributed to the decline of the Egyptian New Kingdom, but researchers now believe that a long period of drought caused by climate change was a major catalyst.

Life in New Kingdom Egypt

Dating from about 1550-1070 BCE, Egypt’s New Kingdom is the most well-documented era in ancient Egyptian history. Some of the most famous pharaohs ruled during this period, including Hatshepsut, Tutankhamun, and Ramesses the Great. These rulers of the Golden Age oversaw nearly 500 years of political stability, economic prosperity, and imperial expansion.

Much of the Mediterranean saw major advances during this time, as the Bronze Age ushered in economic, political, and technological advances. Trade routes expanded, giving societies greater access to resources, particularly bronze tools and weapons that revolutionized both routine work and warfare.

It was also an era of widespread literacy, with specialized artisans, merchants, and diplomats exchanging written communication within Egypt and beyond. Much of the information about this time has come from ancient contracts, bills of sale, and diplomatic letters that have survived through time. The Egyptian Book of the Dead was also created during this period. It is a collection of mortuary texts intended to protect the deceased on their journey to the afterlife.

The New Kingdom era saw a surge in grand architecture and art in ancient Egypt, thanks to funds and resources coming from the far reaches of the empire. With this wealth, pharaohs commissioned monumental temples, statues, and tombs. Famous examples include the Luxor Temple, the Valley of the Kings, and the Temple of Hatshepsut. The interiors of these royal tombs were exquisitely painted and carved with religious texts and images revealing details of life during the New Kingdom.

The Decline of the New Kingdom

After nearly 500 years of unprecedented growth and prosperity, signs of trouble began to surface during Ramesses III’s reign (1186-1155 BCE). Considered to be the last great pharaoh of the New Kingdom, Ramesses III fought to keep the empire intact, defeating the invading Sea Peoples and the Hittites. Unfortunately, other long-standing factors were creating difficulties.

While a strong centralized government persisted through most of Egypt’s New Kingdom, the pharaoh’s power gradually weakened. During the 20th dynasty (1089-1077 BCE), high priests became more powerful, leading to political fracture. Towards the end of the New Kingdom, there were as many as 80,000 priests employed at Thebes, plus more in other cities. Some of the high priests had more wealth and influence than the pharaoh.

While the military conquests of the 18th and 19th dynasties resulted in Egypt’s expansion, the costs of these campaigns led to financial strain. Combined, this financial strain and political fracture likely affected commerce and resource distribution.

Contributing to Egypt’s decline at the end of the New Kingdom was a protracted and devastating period of droughts. Several records detail how Egypt and neighboring territories suffered great losses in agriculture during this period. While Egypt made efforts to adapt to this climate change, it seems that the New Kingdom eventually succumbed to the consequences of these droughts.

Reconstructing the New Kingdom Environment

Researchers have long known that the Levant—modern day Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria—suffered from a protracted drought during the Late Bronze Age, which happens to coincide with the decline of the New Kingdom. The extent of the environmental stress experienced by ancient Egypt was unknown until scientists were able to analyze sediment recovered from dated archaeological sites.

Fortunately, researchers can reconstruct historic climates and ecosystems with pollen recovered from sediment cores collected at archaeological sites. Pollen analysis and radiocarbon dating suggest that climate change may have had a hand in the demise of the New Kingdom.

This testing revealed a sudden decline in pollen from olive trees and Mediterranean trees like oaks and pines. Experts have interpreted this information as a sign of prolonged and severe droughts between 1250 and 1100 BCE. It is thought that by the time the droughts broke, the New Kingdom couldn’t recover due to political fractures, social disruption, and threats from foreign invaders.

Pollen analysis also revealed that Egyptians attempted to adapt to this climate change. Researchers believe that rulers anticipated crop failures in arid regions and ordered increased grain production in areas with more access to water. Analysis of DNA from cattle remains suggests that farmers crossbred their herds with zebu, a more heat-resistant subspecies of cattle.

Archaeologists believe that these efforts may have helped to prolong the life of the Egyptian empire by a few decades. Unfortunately, these agricultural adaptations were not enough for the kingdom to thrive.

Why Would a Drought Contribute to the Decline of the New Kingdom?

Outside of recent scientific research, several historical records make reference to a series of droughts and famines that affected the peoples of the Levant and Mediterranean towards the end of the Bronze Age. During the late 13th century through the early 12th century BCE, agriculture suffered greatly, particularly grain crops.

In a letter to Ramesses II, a Hittite queen told the pharaoh, “I have no grain in my lands.” Egyptian rulers had long been stockpiling grain supplies, so pharaohs of the late New Kingdom did what they could to supply neighbors. These efforts were likely driven by a combination of humanitarian and political motives, and helped the empire survive longer than it would have otherwise.

Regardless of agricultural adaptations and judicious political action, Egypt eventually suffered from debilitating food shortages. Even with access to the Nile, grain production was markedly reduced, which led to depletion in reserves and other staple crops like legumes, lettuce, and flax.

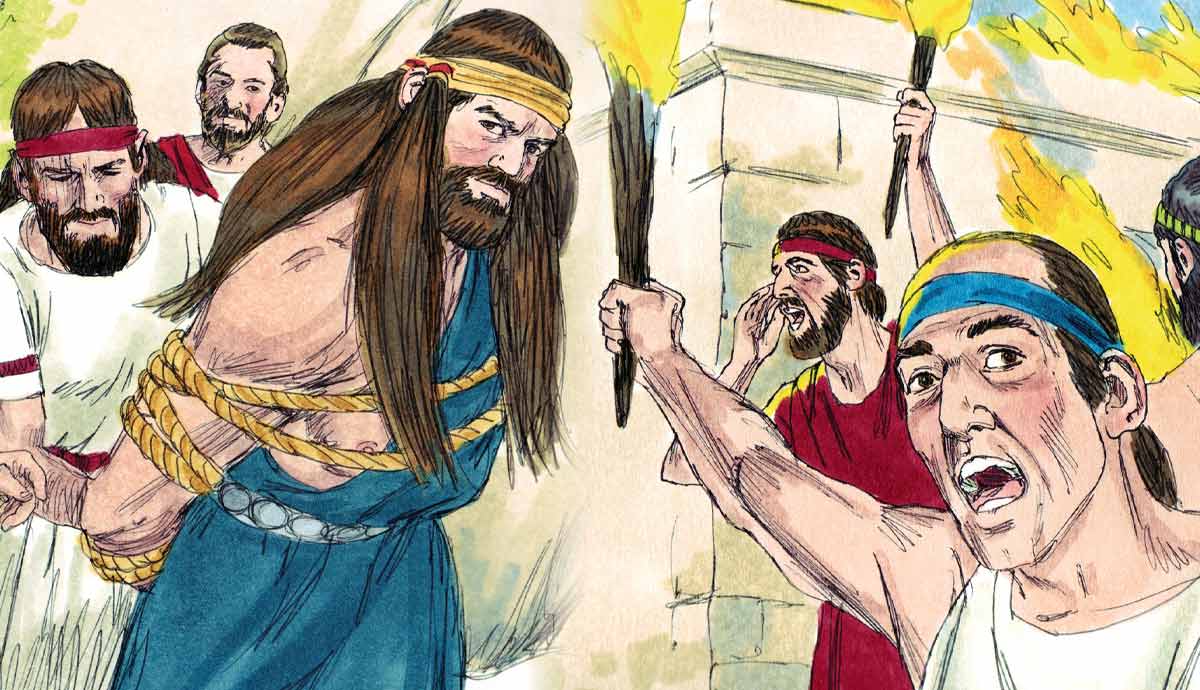

The depletion in grain reserves led to societal unrest, as Egypt was a cashless society at the time. It is probably no coincidence that the first recorded workers’ strike occurred during this time. In November of 1152 BCE, a strike was organized by workmen and artisans who built the extravagant tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

According to the Turin Strike Papyrus, the workers had not received their wages, which were paid in grain rations. This ancient record provides an account of the socioeconomic problems of the time, as well as details on the labor strike by the workmen of Deir el-Medina. In a non-violent show of discontent, the workmen staged a demonstration at Ramesses III’s mortuary temple and a sit-in at the temple of Thutmose III.

Another consequence of the drought was the depletion of lumber supply. While monumental architecture like temples and tombs built by the workmen of Deir el-Medina were typically constructed with cut stone, most other structures and dwellings were built with wood and mud brick. Wood material was either locally sourced or imported from neighboring territories.

Unfortunately, the entire region experienced prolonged droughts simultaneously, resulting in diminished supply of lumber. This likely inhibited construction and structure maintenance that was necessary in the growing cities. It is possible that poor forest management also contributed to the shortage, as the tremendous growth during the New Kingdom required more resources than ever before.

Commerce was also negatively impacted by the extended droughts. Throughout Egypt’s history, economic success was dependent on the trade of agricultural goods. This was especially important during the Bronze Age, as harvests, gold, and other resources were exchanged for bronze, wood, and precious materials like gems and silver.

With the expansion of the empire during the New Kingdom, Egypt had become more and more reliant on long-distance trade networks. As these trade partners suffered the ongoing droughts and famine, these networks broke down.

Unfortunately, the dissolution of trade networks and depletion of resources ushered in an age of competition. Despite all efforts to adapt, the empire’s borders were no longer secure. By this time, Egypt was fighting off threats of invasion.

Several ancient texts attribute the fall of the New Kingdom to the invasion of the Sea Peoples. While there is no firm consensus as to the origins of the Sea Peoples, it is generally believed that they came from areas in the Mediterranean and Aegean that suffered from the same series of droughts.

Eventually, the Egyptian empire began to shrink and weaken. While the decline of the New Kingdom was probably inevitable, the magnificent growth and advancement of this Golden Age have long been admired. The archaeology and written records left behind by this great civilization are some of the most spectacular in the world.

Sources:

Climate Change May Have Brought Ancient Egypt to Its Knees | NOVA | PBS

Vegetation and Climate Changes during the Bronze and Iron Ages (∼3600–600 BCE) in the Southern Levant Based on Palynological Records | Radiocarbon | Cambridge Core

New Kingdom of Egypt – World History Encyclopedia

New Kingdom Egypt: Power, Expansion and Celebrated Pharaohs (thecollector.com)

Egypt’s Golden Empire . New Kingdom . Art & Architecture | PBS

(PDF) Egyptian Imperial Economy in Canaan: Reaction to the Climate Crisis at the End of the Late Bronze Age (researchgate.net)

More Evidence For Crippling Bronze Age Drought – Archaeology Magazine