Demetrius Poliorcetes, “the Besieger,” became central to the scramble for power following the death of Alexander the Great. The drama of his life is such that a historian described it as one that “still awaits a movie producer” (Chaniotis, 2018, 47). Ever-changing fortune cast him down from the pinnacle of power before lifting him up again. His life was also one of contradictions. He was a talented general most famous for his defeats and a capable organizer but dissolute and extravagant. His story is a tale of thwarted ambitions, but he helped shape the emerging Hellenistic world.

The Antigonids and Demetrius

Demetrius was born in Macedonia to a noble family in early 336 BCE, shortly before the ancient world changed forever with the conquests of Alexander the Great (r. 336-323 BCE). There is doubt about whether he was the son or nephew of Antigonus Monophthalmus (382-301 BCE), a significant figure under Alexander. Antigonus himself made no distinction, and the close and trusting relationship between Antigonus and Demetrius became a hallmark of their family, known as the Antigonids.

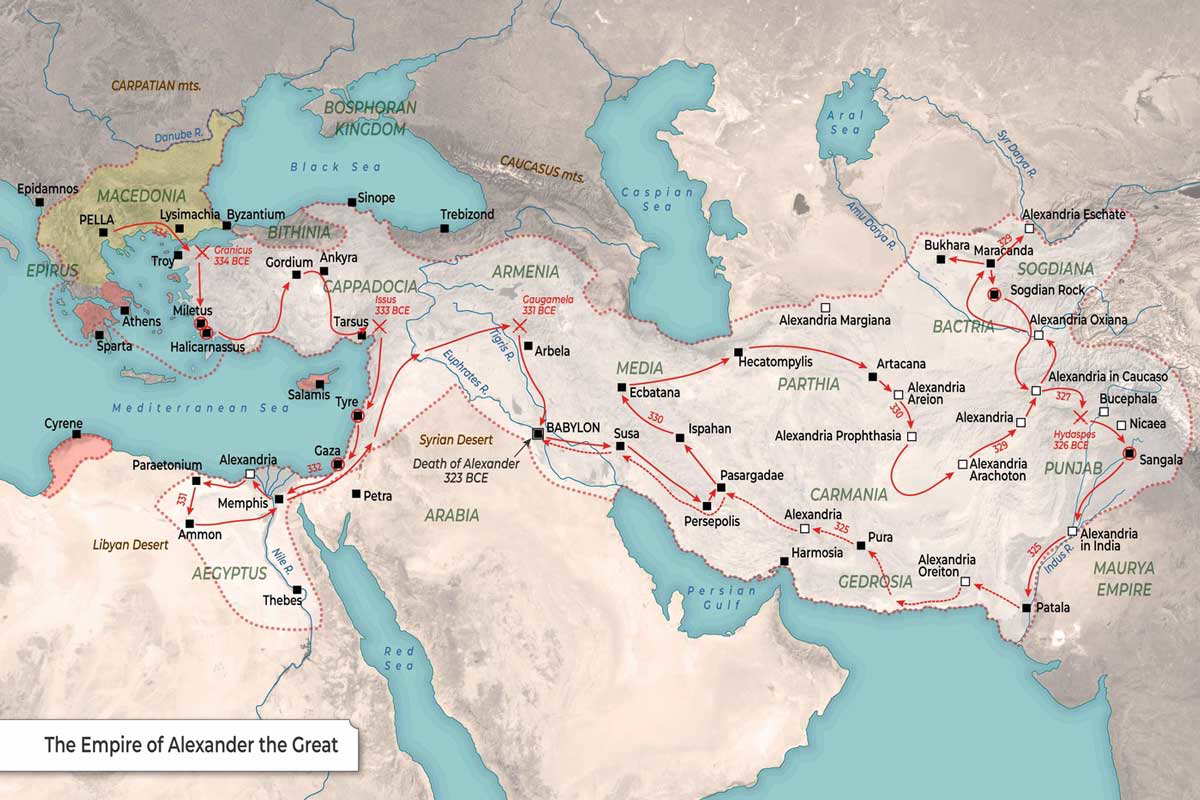

While Antigonus had a long career behind him, he rose to prominence under Alexander as governor of Phrygia (central Turkey) from 333 BCE onwards. The posting was significant for Antigonus and his family, who joined him in Asia. This background makes Demetrius one of the first figures of a new world ruled over by a Macedonian elite.

When Alexander died in 323 BCE, his empire had no obvious king. A son was on the way but was in no position to rule anytime soon. There was a half-brother, Philip Arrhidaeus, but for unknown reasons, he was judged to be unfit to rule. This left a pack of ambitious generals and governors to rule the empire, who became known as the Diadochi, or “Successors.” Antigonus and his now teenage son were amongst this pack of potential successors.

Demetrius’ Early Career

Over the course of four decades, the leading generals fought a series of wars with constantly shifting alliances. Demetrius’ life, from his teenage years up to his death in his 50s, was one of almost constant war.

Demetrius started to play a role before he was out of his teens when he married Phila, the 35-year-old daughter of Antipater, the governor of Macedonia and Greece. Polygamy was a common practice for the male members of the Macedonian nobility, and Demetrius would go on to have several marriages and significant relationships. Despite the age difference, this first marriage seems to have been happy.

Having helped seal an alliance, Demetrius’ next step was to aid his father in war. He first appears in battle as a cavalry commander and then commander of the right wing at the battles of Paraetacene and Gabiene in 317-316 BCE as Antigonus pursued the rival general Eumenes into Persia. Though little is said of Demetrius’ role, his father had enough confidence in his son to leave him in charge of Syria in 314 BCE at the age of just 22.

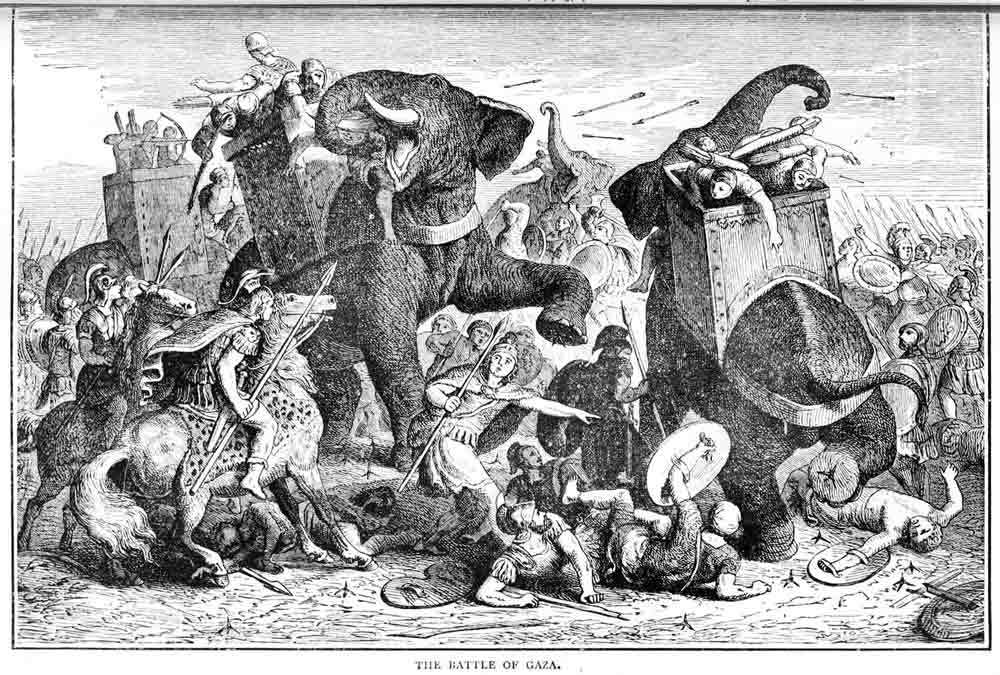

It was in this role that Demetrius experienced the first of many reversals of fortune. He was meant to monitor Ptolemy and Seleucus, two of the most experienced successors. In 312 BCE, Demetrius engaged them in an ill-advised battle at Gaza. This first solo command ended in disaster as Demetrius was beaten and lost much of Syria.

In the aftermath, Demetrius showed his ability to recover, as a victory over one of Ptolemy’s generals limited the immediate damage. Nevertheless, the long-term consequences of Gaza were damaging for the Antigonids. With their power suddenly weakened, Ptolemy released Seleucus to conquer Babylon. Demetrius and Antigonus unsuccessfully tried to dislodge him in the following years, but Seleucus carved out his own empire. In the long run, this development would prove fatal to Antigonid ambitions.

Becoming a King

After an uncertain beginning to his career, Demetrius learned from his mistakes and elevated his family’s fortunes to new heights.

His next major initiative was an invasion of Greece in 307 BCE. The Antigonids claimed to be liberating Greece. In practice, this meant that they would free Greek cities from the control of their rival, Cassander. The first major success of this policy came at Athens. Since its defeat in the Lamian War in 322 BCE, the city had been under Macedonian control, which, in 307 BCE, put it under the domination of Cassander. The Athenians, desperate to end Cassander’s control, greeted Demetrius warmly after he sailed into the harbor of Piraeus.

After removing Cassander’s garrison, the restored Athenian democracy voted honors for Demetrius and his father. Statues were set up, hymns were sung, and even the Athenian local administration was modified to name parts of it after the Antigonids.

In 306 BCE, Antigonus ordered Demetrius to attack Cyprus, which was held by Ptolemy. Upon landing, Demetrius began a siege of the city of Salamis. At Athens, Demetrius had shown a skill for using siege engines to take fortified positions. Outside Salamis, he developed his art further by constructing massive siege towers. However, the fate of Cyprus was decided at sea. Ptolemy himself arrived with a fleet to challenge the man he had brushed aside at Gaza. Though slightly outnumbered, Demetrius won a resounding victory, forcing Ptolemy to abandon Cyprus.

Victory at Salamis had momentous consequences. By 306 BCE, the two kings, Philip Arrhidaeus and Alexander IV, were both dead. The Macedonian throne had been left vacant. Following Demetrius’ recent victories in Greece and Cyprus, Antigonus was clearly the most powerful general. He used his glory to declare himself and his son kings. Not to be outdone, the other generals elevated themselves to kings soon after. The fiction of a united empire was over as the rival generals became rival kings. Demetrius’ victory in Cyprus marked the beginning of a new era.

Demetrius’ First Fall

Demetrius and Antigonus were at the pinnacle of their power, but in the five years following Cyprus, fortune turned, bringing a series of devastating defeats.

The first setback was an invasion of Egypt in late 306 BCE. Antigonus failed to overcome Ptolemy’s defenses on land, while Demetrius was hampered by storms at sea, forcing the Antigonids to withdraw quickly.

The following year saw the famous siege of Rhodes. The Rhodians were a significant naval power, and while not hostile to the Antigonids, they were friendly to Ptolemy. For a year, Demetrius attempted to take the main city of the Rhodians, who resisted fiercely. Demetrius brought into action numerous inventive siege engines, which culminated in the helepolis, which was a massive movable tower. Though it may have been as high as 44 meters and took thousands of men to move, it ultimately failed to force the Rhodians to surrender. Demetrius did not take Rhodes, but the peace terms did give the Antigonids hostages and made Rhodes an ally against all except Ptolemy (Wheatley & Dunn, 2020, 200).

The epic siege is tied up with Demetrius’ nickname, the Besieger (Zielinski, 2023, 122). There is some debate about whether the name was given in admiration or irony. Demetrius, in the end, failed to take Rhodes, and one modern historian described the campaign as an “extravagant waste of time and resources” (Errington, 2008). Others believe the name reflects Demetrius’ inventiveness and points to his otherwise impressive record of taking cities (Wheatley & Dunn, 2020, Zielinski, 2023, Chaniotis, 2018). Given that Rhodes was close to falling and Demetrius had an impressive record of taking cities, plus he started the Hellenistic world’s obsession with ever larger and more inventive siege weaponry, it seems likely the nickname was a genuine reflection on an impressive military reputation (Wheatley & Dunn, 2020, 2-3).

The setbacks in Egypt and Rhodes showed that while powerful, the Antigonids were not invulnerable (Errington, 2008). A coalition of Ptolemy, Seleucus, and Lysimachus formed to confront the Antigonids before their power got too great. In 301 BCE, the Antigonids faced the combined armies of Lysimachus and Seleucus at the battle of Ipsus. With more than 150,000 men involved, along with hundreds of elephants, Ipsus was an era-defining battle. Initially, Demetrius gained the upper hand as he once again commanded his father’s right wing and drove back his opponents. However, he rode on too far, and Seleucus blocked his return to the battlefield with his elephants. Antigonus, now in his 80s, was overwhelmed in the center and fell, still believing Demetrius was about to return and save him (Plutarch, Demetrius, 29).

Just five years after reaching the height of its power in Cyprus, the Antigonid empire seemed to be over.

The Return of Demetrius

The death of his father and the loss of almost all his former empire was remarkably not the end of Demetrius.

Despite treating him like a god, the Athenians shut their gates to Demetrius after Ipsus. Following their initial enthusiastic, even sycophantic, welcome of Demetrius, the relationship soured. A second stay in the city before Ipsus saw Demetrius elevated to divine status as he was allowed to live on the acropolis, an unheard-of intrusion in the sacred space. His lavish lifestyle and his habit of inviting the famous beauty Lamia, along with numerous women and young men of Athens, into the house of the gods, plus his inclusion in the Athenian sacred calendar, alienated many Athenians. Demetrius’ later biographer Plutarch (Demetrius, 19-20) commented that Demetrius dedicated himself to whatever he was doing. In war, this was a virtue as he was sober and organized. In peace, this could be a vice as his dedication turned to luxury and extravagance.

Demetrius still retained a powerful fleet and a number of coastal cities in Greece, Lebanon, and Cyprus. Clinging onto this foothold made Demetrius relevant again a few years later. Though he had done the most to defeat the Antigonids, Seleucus sought an alliance with Demetrius in 299-298 BCE and married Demetrius’ daughter Stratonice.

In 294 BCE, the next major opportunity presented itself. Cassander, king in Macedonia, had died in 297 BCE, and within a few years, his dynasty was reduced to two young and squabbling successors, Antipater and Alexander. When Alexander called for Demetrius’ aid, the far more experienced king simply moved north, had Alexander killed, and took over.

Demetrius’ proclamation as king of Macedonia in 294 BCE marked another remarkable turn of fortune. After Ipsus, he was little more than a fugitive. Now, he was back in his homeland for the first time since childhood and was once again an equal to any of Alexander the Great’s successors.

Demetrius’ Second Fall

Demetrius was king in Macedonia, but his position was far from secure. On his borders were the powerful kings Lysimachus and the ambitious young warrior Pyrrhus. Further away, the alliances he had made with Seleucus and later Ptolemy were, at best, weak bonds.

For Demetrius, Macedonia does not seem to have been an end in itself. He used the country to rebuild his forces to reconquer his father’s lost empire. For the Macedonians, it seemed like Demetrius’ ambitions were simply draining them as he invested their money, men, and resources into his armies and fleets. Macedonian kings were meant to be somewhat accessible and responsive to their subjects. Demetrius appeared distant and arrogant. Furthermore, the failure of a campaign against the Aitolians and Pyrrhus made him appear ineffective (Chaniotis, 2018, 45).

By 288 BCE, Demetrius’ preparations prompted a coalition of Pyrrhus, Lysimachus, and Ptolemy to act. Caught between Pyrrhus and Lysimachus, his support evaporated, forcing Demetrius to flee Macedonia. A further blow came as his first wife, Phila, died or committed suicide as Demetrius fled. Once again, his fortunes had abruptly turned.

This time, despite another attempt, there was to be no recovery. His remaining forces and his son Antigonus Gonatus still held some positions in Greece. Despite losing Macedonia, Demetrius took what soldiers he could and headed east. In a final campaign between 287/6 and 285 BCE, Demetrius tried to win over some of Lysimachus’ cities in Asia Minor. Eventually, Seleucus cornered him in Cilicia (south-east Turkey) and compelled him to surrender. Demetrius’ tumultuous career finally ended as a prisoner. Seleucus was not harsh and allowed his fellow king to live out the last few years of his life in comfortable captivity in Syria. It is even said that, after all the years of battles and campaigns, Demetrius came to enjoy his enforced leisure before he died aged 54 in 282 BCE (Plutarch, Demetrius, 52).

Given that it ended in captivity, it would be easy to see Demetrius’ life as a failure. At one time, the empire of Antigonus and Demetrius was the most powerful force in the post-Alexander world. Both ended in defeat. It has been said that, like Alexander himself, he knew how to fight a war but not how to administer an empire (Errington, 2008). All of that is true, but despite the defeat of his own ambitions, Demetrius helped shape the world that was to come. The Antigonids were the first to publicly acknowledge the new reality by declaring themselves kings. Furthermore, Demetrius’ son, Antigonus, still lived and, in time, gained the Macedonian throne. Through many twists and turns, the Antigonids ultimately became one of the three great powers of the Hellenistic World.

Selected Bibliography

Chaniotis, A. (2018) The Age of Conquests: The Greek World from Alexander to Hadrian, Harvard University Press.

Errington, R.M. (2008) A History of the Hellenistic World: 323 – 30 BC, John Wiley & Sons.

Whealey, P. and Dunn, C. (2020). Demetrius the Besieger, Oxford University Press.

Zielinski, T. (2023) “Demetrius Poliorcetes’ Nickname and the Origins of the Hostile Tradition Concerning his Besieging Skills,” Ancient History Bulletin, 37.3-4: 120-141.