The Sino-Japanese War was raging in 1937 when Japanese troops closed in on the capital of the Republic of China at the beginning of December. Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of the Republic, knew from the invasion and subsequent capture of Shanghai in August that Nanjing would fall to the Japanese in only a matter of time. The Japanese troops continued rolling through China throughout 1937, leading to so many atrocities that the war was characterized as the “Chinese Holocaust.” This is the story of one such horror, the Nanjing Massacre.

What Led to the Destruction of Nanjing?

Chiang Kai-shek and his government knew that as soon as Japan entered Manchuria, they would go for the capital of the Republic of China in Nanjing. After the Battle of Shanghai, the Generalissimo, as Kai-shek was known, saw the Japanese approaching and fled.

The official stance of the Chinese government was that they could not risk losing their elite military members to an all-out invasion of the capital. However, publicly, military commander Tang Shengzhi stated that Nanjing would not surrender to the Japanese and that the Republic of China would fight to the death.

While technically true, this press release did not allude to who would defend the capital city. The city was to be guarded by a relatively small number of soldiers while the government retreated and fled further inland. Tang mustered around 100,000 men to defend the city, and while this was no small number, the troops were largely untrained and were left under the guidance of an international committee for the safety of Nanjing.

The Japanese arrived at the city gates on December 9, 1937, and began dropping leaflets into the city, calling for surrender within 24 hours. If there was no surrender, the flyers warned, there would be no mercy from the Japanese military upon invasion.

John Rabe was the German national left in charge of Nanjing. He quickly advocated for a three-day ceasefire with the Japanese and pleaded with the Chinese government to allow the withdrawal of troops so that there would be no military operatives in the city. However, both the offers sent to the opposing sides were rejected, and Rabe was left in a position to defend his adopted city with very few resources and unskilled soldiers.

Rabe could see that the city’s fate had been sealed in its abandonment by the Chinese government. The capital was bombed for days during the first week of December, and the troops left in the city took to drinking, knowing that the downfall of the city they should have been defending was inevitable.

The Invasion and Battle of Nanjing

After receiving no word as to the surrender of the city by the deadline of December 10th, Japanese forces began invading the city from all sides. General Tang Shengzhi, with no real ability to defend the city, ordered his troops to retreat on December 12th while the city was facing heavy artillery fire and bombings.

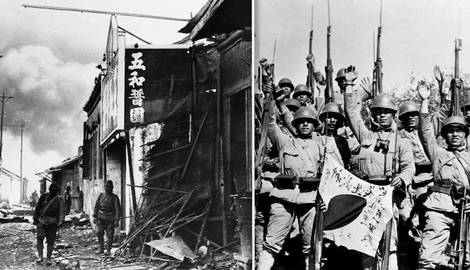

The retreat was, in short, disastrous. Chinese soldiers did whatever they could to blend into the civilian population, even going so far as to strip actual civilians of their clothes and belongings. In an attempt to flee, many of the Chinese troops were shot by their supervisory unit as well. In the wake of their desertion, Chinese troops set fire to as much of the city as they could, trying to limit the amount of destruction that could be wrought by the Japanese.

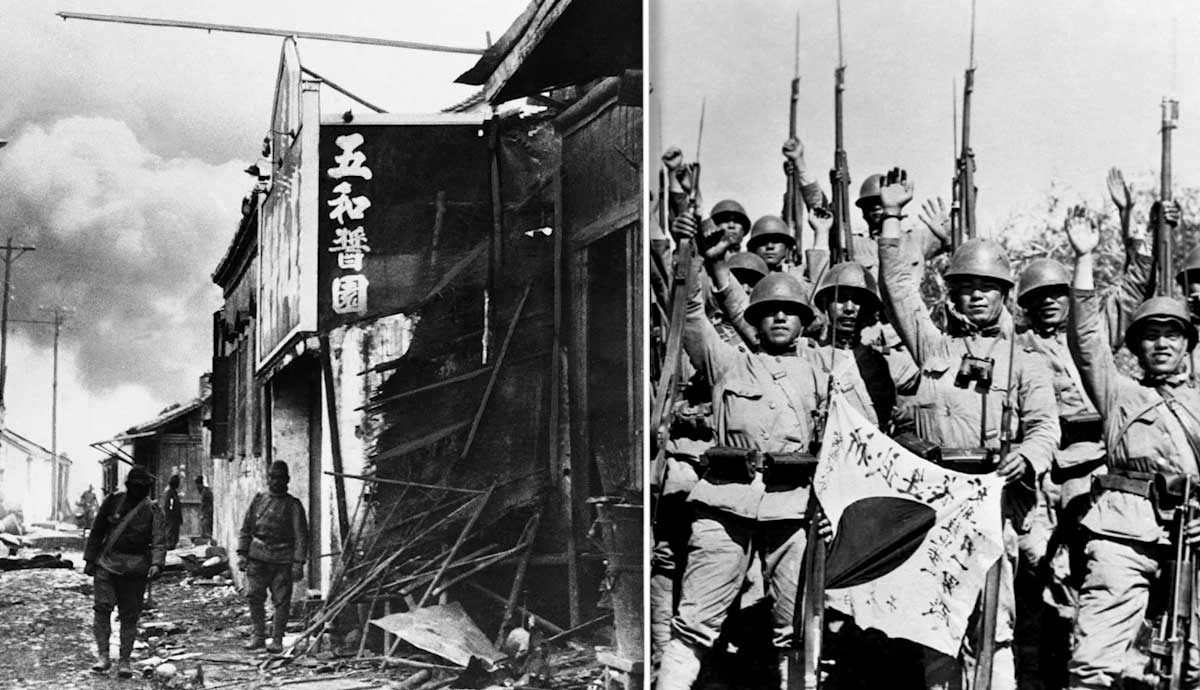

Upon breaching the walls of the city, the 6th and 116th divisions of the Japanese Army were the first to enter the city of Nanjing on December 13th. They encountered little military resistance and cleared the way for several more troops to invade the city, along with two navy fleets who docked their ships on the banks of the Yangtze River.

It was upon their entrance to the city that the Japanese troops began pursuing the fleeing Chinese forces, mostly to the north of the city. The Chinese troops were, by most accounts, facing an all-out, one-sided slaughter during the final days of resistance. However, some Japanese historians argue that the actions of the Japanese were justified insofar as the Chinese still posed a major threat to the Japanese Army.

This “mopping-up” operation of the battle also applied to refugees who remained in the Nanjing Safety Zone, a 3.85-square-kilometer (or 1.5-square-mile) area where the remaining population of Nanjing was residing. While nearly three-quarters of the people had already fled, those left behind were put under guard in the Safety Zone.

Many who had escaped the city were the city’s wealthier residents, and those under Japanese occupation were poorer and unable to find the resources to flee upon invasion. While even the middle and some lower classes fled, those who were destitute remained to face whatever brutality the Japanese had planned.

The Destruction of Nanjing

The 50,000 soldiers who invaded Nanjing in December of 1937 began their campaign of terror against the Chinese troops who remained in the city. The Japanese looked upon these prisoners of war with particular disgust, as surrender in Japan was seen as the ultimate act of cowardice and disgrace. These POWs were thus treated as subhuman, an exercise in how to inflict pain and kill effectively for the Japanese army.

The Chinese troops who were left in the city were driven to the outskirts by the truckload, and as soon as they were assembled, the carnage began. Japanese soldiers were instructed to attempt to inflict maximum pain on their captives and to eliminate any notion of mercy they had. Photographs document the massacre, with Japanese soldiers using living POWs for bayonet practice, mowing them down in large swaths via machine gun fire, decapitating, and burning the men alive.

After about a week, approximately 40,000 Chinese men, whether they were POWs or just of draft age, were dead. The Japanese troops then turned their sights on the civilians of Nanjing, whether or not they were living within the safety zone. The claim is that the Japanese division commanders did not necessarily authorize the brutality that followed, but even so, they did nothing to stop it.

Unruly and drunken bands of soldiers began roaming the streets of Nanjing, searching for women. When they found them, they would brutally rape them, whether in the street, in stores, or even in homes in front of the women’s families. Many such women were then violently murdered and mutilated to ensure that they could never bear witness against their attackers—estimates of the number of women sexually assaulted range from 20,000 to 80,000. The victims ranged in age from 10 to 60 by most accounts, and pregnant women were not spared from the brutality.

Anyone who attempted to resist the Japanese attacks was killed on the spot. Japanese troops went on random sprees of killing, looting, and burning with impunity. Some reports claim that Japanese soldiers would pilfer stores and subsequently lock patrons and workers inside the store, setting fire to the building and trapping the people as they left.

The death toll was hard to calculate because so many Chinese people had been burned or buried in mass graves after their deaths. In addition to this, the majority of Japan’s wartime records were destroyed, meaning that we may never know how many people suffered brutality during the six-week siege of Nanjing.

The Aftermath

The destruction of Nanjing ended after the Japanese troops gradually withdrew in the early days of 1938. A new provisional government had been established, and it looked as though a world war was on the horizon. General Iwane Matsui of the Japanese Imperial Army, at least by anecdotal accounts, regretted his troops’ actions in Nanjing before the incident had even come to pass.

Though it was claimed that Matsui and the other commanders of the Japanese army felt remorse for what happened, we may never know if that was true, as they were almost directly sent back to Japan following the end of the occupation of the Chinese capital city.

No Japanese soldier answered for the destruction wrought in Nanjing until the end of the Second World War in 1945. Shortly after their surrender, Japanese officers in charge of the troops at Nanjing were put on trial for the atrocities they oversaw and committed. General Matsui and the Prime Minister of Japan, Kōki Hirota, plus five other war criminals, were sentenced to death for their crimes.

The tribunals found that at least 20,000 women and girls were raped during the siege, and the death toll was estimated to be close to 200,000 civilians. Though the massacre was documented by the Japanese and investigated by the Allies following the war, there is much controversy surrounding the destruction of Nanjing in modern Japan. Two main camps have arisen: those who agree with the Tokyo Trials (the name given to the tribunal of those involved) and those who think that the massacre was fabricated or exaggerated so the Allies could mete “victor’s justice.”

The truth of what happened in Nanjing in late 1937 will probably never be known. However, the death and destruction inflicted are certainly true, and most historians agree that the Japanese Imperial Army severely fractured the bounds of war and civility in committing such acts.