Divisionism was an artistic technique that relied on constructing images from small primary-colored brushstrokes that would supposedly mix in the viewers’ brains into a complete picture. Colorful and bold, these paintings offered a radically different way of perceiving art. Popular from the 1880s until the first decade of the 20th century, Divisionism was hated by most art critics but still loved by progressive radical artists. Read on to learn more about Divisionism and its creative legacy in modern art.

The Scientific Roots of Divisionism

Divisionism was a Neo-Impressionist painting technique that was heavily based on studies of optics and light. It was a direct heir to the Impressionist movement, which blended these studies with the subjective impression of a fleeting moment. In 1839, a French chemist called Michel-Eugene Chevreul published a study On The Law of Simultaneous Color Contrast. In this writing, he researched how adjacent colors influenced each other and affected their perception by the human eye. Apart from chemistry experiments, Chevreul made a living by restoring old tapestries. This occupation gave him enough material. Another influential text was the English book Modern Chromatics, written by Ogden Rood. Rood established the principles of color contrast and harmony, as well as the visual and emotional effects of color combinations. Nineteenth-century researchers of optics believed that the human brain combined complex colors from small primary-colored dots.

French artists were the first to turn these theories into artistic practice. Painters like Camille Pissarro, Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, and others started to create mosaic-like compositions from unblended primary colors. When placed close to each other, these fragments turned into complex and detailed images. Similar to Impressionists, Divisionists were preoccupied with the effects of light, both natural and artificial, on space and color. They believed that by positioning primary colors close to each other, they could achieve greater luminosity and more nuanced tones.

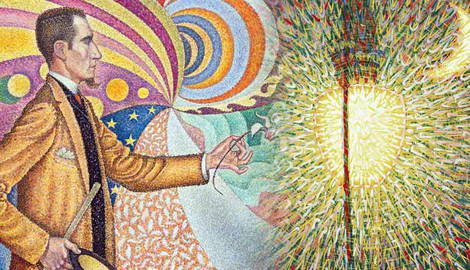

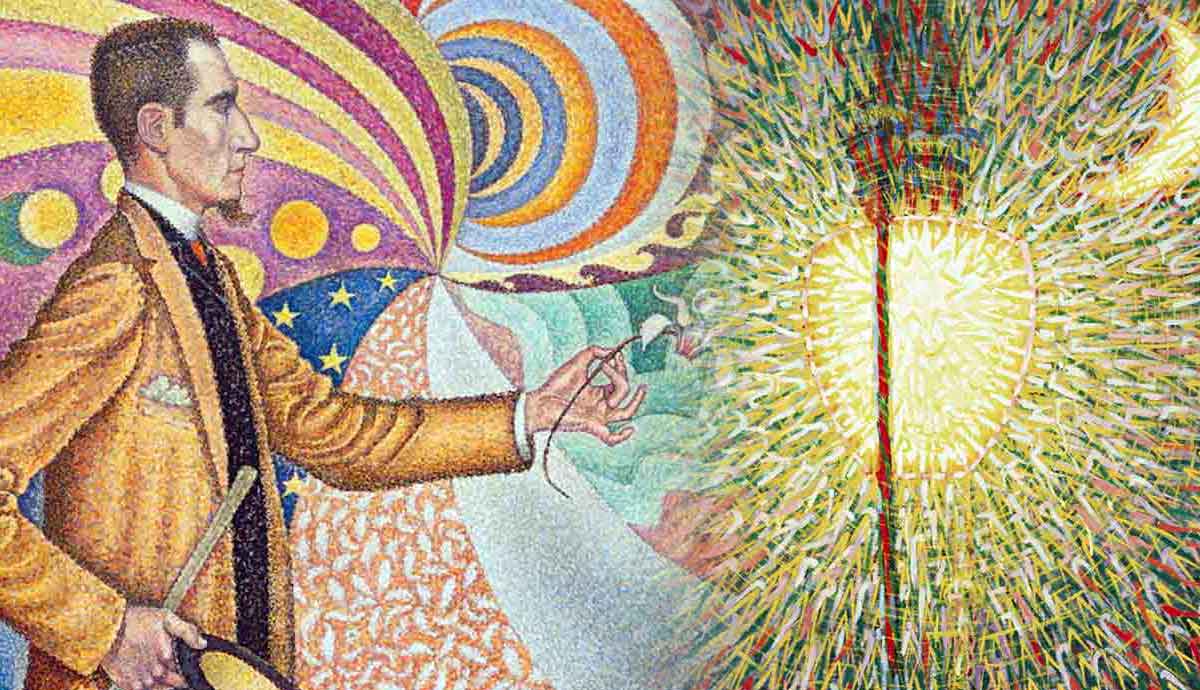

One of the most radical proponents of Divisionism in painting was a famous anarchist and art dealer Felix Feneon. Feneon was a controversial figure in his time, loved by avant-garde artists but despised by the conservative crowd. Feneon was a patron and supporter of young Henri Matisse and Georges Seurat at a time when they were absolutely unknown and unappreciated. He believed traditional museums were cemeteries that halted the development of modern art, and funded exhibitions and publications to bring progressive artworks, including those by Divisionists, to a larger public. For him, radical politics and radical art were the same, contributing to one another and progressing hand in hand. Feneon’s support of arts made him the main character of one of the most famous Divisionist paintings of all—a portrait by Paul Signac in 1890.

Italian Divisionism

The movement’s further development can be traced back to Italy at the moment of its difficult and long reunification. Until the 1860s, Italy was a cluster of city-states and kingdoms in constant conflict with neighbors, endless territorial claims, and a deep sense of cultural superiority despite the poor state of its economy and infrastructure. With the country’s long and bloody unification came the need to forge a shared cultural identity for diverse regions and cultures.

Building cultural identity on the art of the shared Italian past was a dangerous decision since every region had its own nuances. Moreover, the newly united country needed a boost into the future, and the obsession with the remains of the past could slow down the progress, turning the country into a decaying open-air museum. Starting in the 1880s, Italian artists started to look for a modern language of painting and eagerly adopted divisionism as a suitable option.

However, Divisionist painting offered a technique rather than a complete artistic movement, packed with style and subject matter. Thus, although Italian artists of the last decades of the 19th century relied on the avant-garde look of it, their subject matter remained deeply rooted in the Renaissance past. Early Italian Divisionists often painted religious scenes, sometimes in the form of triptychs similar to altarpieces. These choices presented a radical contrast to the French Divisionists who, like Impressionists before them, focused mostly on urban scenes and modern social settings.

Some artists, like the famous Italian Giovanni Segantini, applied the Divisionist technique to Symbolist subject matter, creating dramatic landscapes, gentle images of motherhood, and gruesome punishments for evil femmes fatales.

Despite seeming rather simple, Divisionism was a shock for the Western crowd of art professionals and lovers. It presented a radically different way of interacting with images and an alternative way of coding reality into portable painting form. The critical response was mostly negative, especially coming from the conservative Italian press. Apart from a clear fear of innovation, critics expressed concerns with the fact that Italian artists were learning from their French colleagues. The fear of cultural and aesthetic homogenization stood in the way of appreciating local developments and the unique qualities that differentiated French and Italian modern artists. Critics called divisionist works painted measles and compared them to embroidery, but not in a favorable way. In France, great artists like Claude Monet and Pierre Auguste Renoir refused to exhibit their work in a space shared with the Divisionists.

From Divisionism to Futurism

A decisive turn happened when the technique was adopted by one of the most radical and provocative groups of young artists of the 20th century. The Futurists declared the utter rejection of everything associated with old times and old culture and called for radical modernization of Italy. Modernity became the new religion, with heavy machinery and roaring mechanisms replacing traditional aesthetic categories of art and music. Divisionism was the first logical step undertaken by those looking to shake off the legacy of the past centuries.

Politically, Divisionism represented a more intellectually accessible form of art that did not require amassing any amount of extra knowledge of symbols, iconographies, and traditions. Mostly, it dealt with modernity and used a technical, non-allegorical language. For Futurists who saw their goal to get rid of traditional forms, symbols, and perceptions of art, the bright and dynamic look of Divisionist art was the first step to finding the solution. One of the leading Futurists, Giacomo Balla started his career by painting bright Divisionist canvases of street lights and city balconies. The play of light, reflected by the short colorful brushstrokes showed the complexity of artificial light that finally became widespread.

Pointillism

Frequently confused with Divisionism, Pointillism was another artistic technique that branched out of it. While divisionist art dealt with paint applied in small strokes, pointillist paintings consisted of tiny adjacent dots. Pointillism did not rely as much on color theory as Divisionism did. It was developed and practiced by the same artists though—Paul Signac and Georges Seurat.

Pointillism was short-lived and less versatile than Divisionism. Pointillist canvases emphasized the technique, while Divisionism offered a wider stylistic and political diversity.

The Legacy of Divisionism

What was first perceived as painted measles soon became popular enough to appear as a norm, at least in the works of progressive avant-garde artists. Vincent van Gogh’s unique style featured elements of Divisionist painting, with small separate strokes combined into a complex whole. In his technique, Van Gogh relied heavily on impasto—a textured layering of thick strokes of paint that gave extra expressive potential and volume to his compositions.

Apart from France and Italy, Divisionism became popular in the Netherlands. The famous abstract artist Piet Mondrian adopted a similar technique that would later transform into his signature geometric abstraction, composed of small colorful blocks. For a while, great artists like Pablo Picasso and Gino Severini worked in Divisionist technique too.

Generally, Divisionism was rather short-lived, with its theoretical claims soon disproven by practice. However, art historians believe that the movement served as the crucial step in developing a radically new approach to modern painting. Divisionism offered a new way of constructing the artificial painted reality by building the image from small blocks of paint, rather than from lines imitating nature. It also made modern artists less afraid of pure bold color, which would soon manifest itself in abstract art.