There is often a great conflict in art when the personal behavior of an artist diminishes his work. Many believe the art and the artist should be held separate, a reasonable approach that is simply not possible in some situations. An artist may entrench themself so deeply in the work that there is no escape. In regards to film, no artist embodies this problem more than the controversial D.W. Griffith.

D.W. Griffith: On the Frontier of Cinema

Born January 22nd, 1875 on a Confederate Kentucky farm, David Wark Griffith was raised as a Methodist and educated by his older sister Mattie. After his father passed away, Griffith left high school to support his family by working in markets and bookstores. The economy of the South had been radically changed after the Civil War and currency became essential due to the abolitionist movement. This led Griffith to turn to the arts for income, touring with theater companies as an actor in order to make money and learn how to be a playwright. Every company rejected him until Edison Studios producer Edwin Porter offered Griffith a part as an extra in one of their films.

Griffith began his film career in 1908 as a stage extra for the Biograph Company, which produced over 3000 short films and 12 features during the silent film era. This same year, Biograph’s lead director Wallace McCutcheon fell ill and Griffith was the only suitable candidate who could replace him, directing 48 shorts in his place. His most prominent early work was a 1909 adaptation of Charles Dickens’ The Cricket on the Hearth where he revolutionized the technique of cross-cutting, an unpopular choice at the time. Griffith was immediately challenging the conventions of cinema and he seemingly foresaw where the medium was going.

In 1910, Griffith migrated to Hollywood and spent the next four years working towards his first feature, resulting in 1914’s Judith of Bethulia. He was met with concern by Biograph as they believed that hour-long films were not viable because they would hurt the eyes of their audiences. Griffith left Biograph and began co-producing films with other filmmakers until he met studio executive Harry Aitken, the manager of Majestic Studios. The two producers formed Reliance-Majestic Studios, later renamed Fine Arts Studios, and attracted another benefactor in Keystone Studios. All of a sudden, they were the Triangle Film Corporation. With these resources and creative freedom, Griffith was able to make what would be his most successful and dangerous film.

The Birth of a Nation

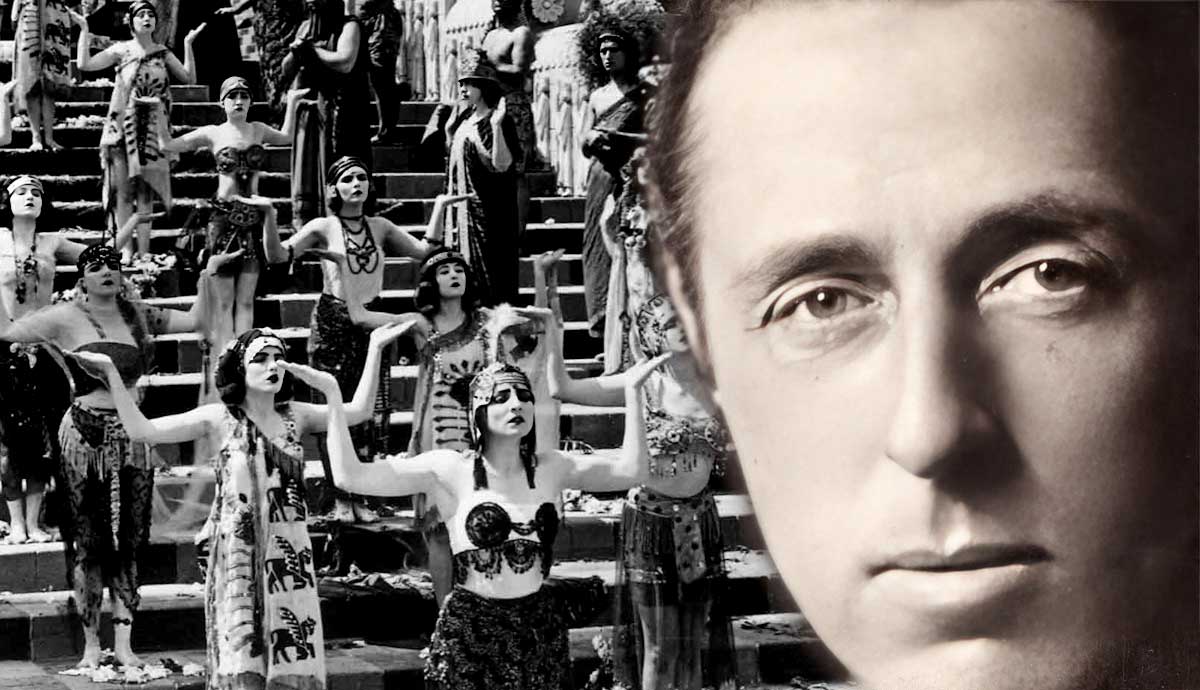

Originally titled The Clansman after its source material, the 1915 Birth of a Nation changed cinema, and media for that matter, forever. This three-hour silent epic is an adaptation of Thomas Dixon Jr.’s 1905 novel and it depicts America from the start of the Civil War to the end of Reconstruction. It was the first feature film to be accompanied by a musical score. It was also a visual game-changer that employed closeups, fadeouts, and large swaths of extras. The visual storytelling of Birth was truly the first of its kind. In regards to the story itself, this is where the fatal flaws emerge.

A key story element in the film is the political aftermath of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, namely the refueled rivalry between the North and the South. While this context is true, the events that follow are despicably fabricated with the intent of degrading Black civilians to maintain White Supremacy. Not only does the film claim that Black voters committed election fraud but that the majority of the South Carolina legislature was Black and denied White votes. To suggest that any of this happened or could happen is pure lunacy. The racism, which clearly reflects the views of Griffith and most of America at the time, is as blatant as the deceit. It is from these preposterous crimes that the bigoted White characters decide to form the Ku Klux Klan to prevent further injustices against the so-called honest men.

The Klan’s white hooded sheets were inspired by White children who dressed up as ghosts to scare Black children. They are treated as heroes for lynching an offensively mischaracterized Black army captain, promoting vigilantism, and, in the end, intimidating Black civilians from participating in their election. It is one of the most disgusting films ever made for its ethical and humanitarian misdeeds yet it is also one of the most technically impressive productions of all time. The former is simply too repulsive and evil to ignore, turning the latter into what is literally one of the worst things to ever happen in Civil Rights history.

Cinema Bleeds Into Reality

The KKK was on the verge of extinction in 1915 until the film’s mythological portrayal of the terrorist organization emboldened new members. It instantly became one of the highest-grossing films in the young history of cinema and it was labeled the first blockbuster ever. To this day, the areas in which the film was popularly screened continue to fester with White supremacist hate groups. The National Association of the Advancement of Colored People rightfully attempted to ban the film but were unsuccessful and the damage that was done to society has been irreparable. Members of the NAACP were not discouraged and went on to heroically protest at screenings of Birth.

Griffith’s romanticized art was motivated by his hatred of those who were not like him and that fury was transposed into a dangerous spectacle. As painful as it is to admit, Birth’s impact on cinema has been undeniably constructive and nothing like its social contributions. Roger Ebert writes in his review that Griffith assembled and perfected the early discoveries of film language, and his cinematic techniques that have influenced the visual strategies of virtually every film made since; they have become so familiar we are not even aware of them. Of these aspects, the most notable is Griffith’s shot selection, weaving expansive wides with intimate close-ups.

But as stated before, the movie’s agenda was too problematic for critics to ignore and Griffith was properly blasted by those who stood with the NAACP. In response to the backlash, the next film by Griffith was Intolerance, a centuries-spanning melodrama that was designed to fight back against his detractors. He pretended to be the victim for the rest of his career and never showed any remorse for the real-life anti-Black violence he was responsible for.

Intolerance explores its titular theme with these four moments: The Fall of Babylon, the Crucifixion of Jesus, the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, and the rise of capitalism in America. The 197-minute epic was largely financed by Griffith and was a box office disappointment after the smash of Birth, leaving the filmmaker in financial ruin. This had him pivot to the executive route where he would go on to found United Artists in 1919 with Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, and Mary Pickford. The studio was off to a nice start until the 1924 romantic drama Isn’t Life Wonderful which was the final box office bomb that blew Griffith’s career to bits.

D.W. Griffith’s Final Films

Griffith made his two full-sound films at the start of the next decade: the 1930 historical drama Abraham Lincoln and the 1931 crime drama The Struggle. Neither made sufficient grosses at the box office and, just like that, filmmaking was no longer viable for the 56-year-old journeyman. Griffith’s final work on a film was in done on Of Mice and Men which he produced and asked for his name to be removed from its billings prior to release.

He would go on to live the rest of his life alone in Hollywood where he passed away on July 23, 1948, at the famous Knickerbocker Hotel. Despite his highly controversial behavior, filmmaking legends such as Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, and Sergei Eisenstein cited him as one of the greatest forces behind the motion picture camera. It is with this that the opening challenge is reiterated: can an artist be separated from their art even if it is detrimental to society? The answer lies in the eye of the beholder, who is also hopefully using their brain and heart when making a verdict.