Since the emergence of civilization, nations have traded goods with their neighbors for resources they lack. They have also exchanged ideas in the form of culture and technological advancement. For countries with rigorous written records and intact archaeology, we can trace back the emergence of the earliest trade networks from their civilizations’ founding stones. However, for cultures without written history, we must rely on archaeology, oral traditions, and accounts from those outside of that cultural sphere to judge the rest. All avenues will need to be explored to uncover the emergence of the earliest trade networks.

Historical Bias and the Earliest Trade Networks

The emergence of trade between Europe, Asia, and the Pacific is complex to describe in simple terms. We are dealing with vast centuries and trying to piece together a world history that spans seven continents and countless cultures. Take, for instance, the case of the Pacific countries. Here we see that archaeology reveals that they had the nautical capability to traverse vast stretches of ocean, yet, they didn’t have written histories documenting how far they ventured, even if their oral histories shed some light on it. Debates about the reliability of oral histories can be seen in the recent discussions about whether Polynesians were the first to visit Antarctica. It has since been concluded that oral histories should weigh more heavily in discussions about the past. So what is shown here is that although attempts are made to tell the story in this tale, some truths will inevitably be left out.

Ancient European Trade Routes to the East: Ancient Greece and Rome

It is best to begin with what history and archaeology are most confident on: Ancient European trade routes. Studies into the earliest emergence of trade between Europe and Asia go back as far back as the ancient Greeks. However, the most substantial evidence comes from the Roman period based on archaeological and written records.

Alexander the Great’s Empire reached as far east as the Indus River. His efforts led to direct interaction between Greeks and Indians, and after Alexander’s death, they flourished. This intercultural dialogue continued, leaving material evidence in the area’s art, seen in the Hellenistic Kingdoms of Bactria and the Indo-Greek Kingdom that welcomed Greek presence for centuries.

Senior Archaeologist Li Xiuzhen, from Emperor Qin Shi Huang’s Mausoleum Site Museum, reported that almost 1,500 years before Marco Polo, the terracotta soldiers at the Tomb of the First Emperor of China (Qin Shi Huang Di) might have been produced by Chinese sculptors inspired by emerging Greek art. This shows evidence of an early Silk Road trade network that emerged following Alexander The Great’s death around 210 BCE. However, we will likely never know whether this opinion is true or not. Still, we can’t deny that by the emergence of the Roman Empire, both regions knew about each other based on the written records of scholars from both sides.

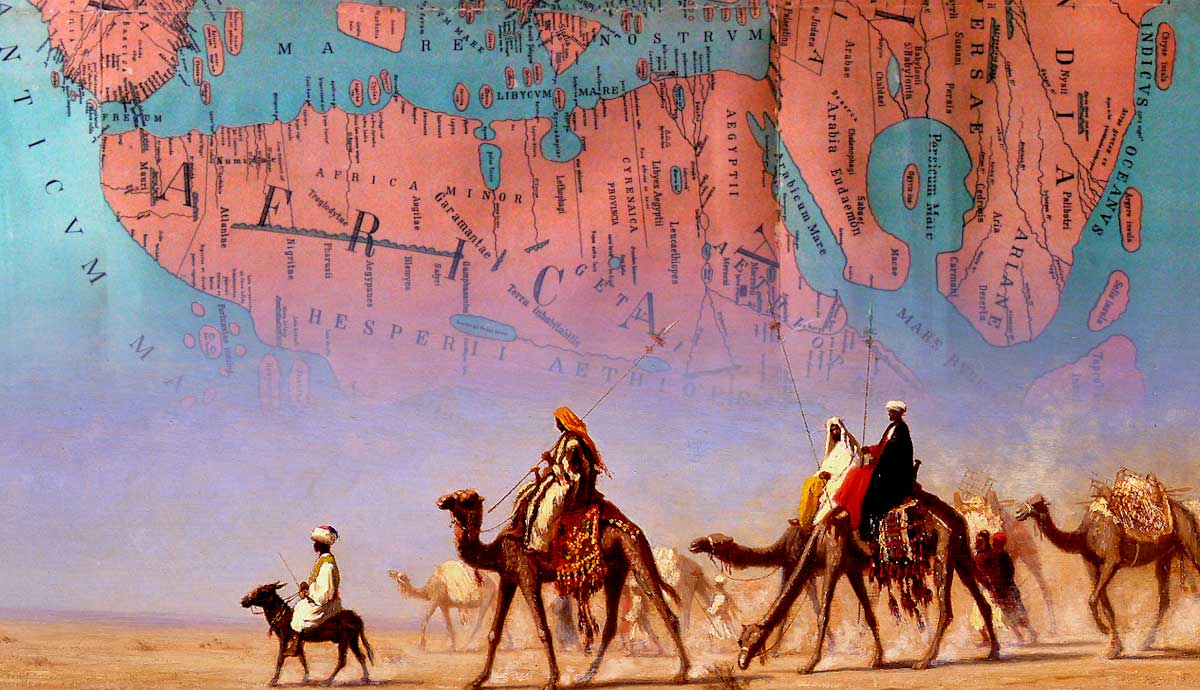

In ancient Rome, we find the first clear evidence of early trade networks with Asia as the empire expanded its borders out in all directions. The Romans didn’t have realistic, accurate maps like the ones we have today, yet they could traverse and keep track of a vast network of roads and territories that made up a large empire. When traveling these roads, they relied heavily on first-hand accounts of locals and past travelers.

After conquering the Mediterranean, the Romans set their sight on East Africa, establishing trading posts as far southeast as the Farasan Islands. These new strides established the Roman eastern border with Persia as far as the Persian Gulf. Trade was established on these forefronts, with networks reaching far into Asia and Europe, peaking at around 100 CE.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, dated to 50 CE, is the primary source for the Roman trade networks of the Indian Ocean. It details the names of cities, countries, rulers, people, traded goods, and Roman trading posts, providing an excellent geographic overview of the extent of Roman trade with Asia.

These established coastal trading posts near the Indian Ocean were vital because they offered a direct link to India, China, and the rest of Asia. This ocean trade would supply the Roman elites with ivory, spices, gems, and silk. Moreover, it widened the Roman view of the world. However, the network fell shortly after the conquest of Egypt by the Arabs in the mid-seventh century.

The Extent of Asian Trade Routes

We already established what trade between the West and Asia was like from the western perspective. So now it is time to see how Chinese Chinese historians document the other side of the story, starting with the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 CE).

The Records of the Grand Historian and the Book of Han record relations between the Graeco-Indian Kingdom and China during the Han dynasty. Zhang Qian, who traveled far west with followers to establish diplomatic relations with western countries, brought back information to the Imperial Court of Wudi of the Han dynasty (c. 114 BCE). During his travels, he established contact with the Hellenistic culture still present in the east after Alexander the Great’s conquests. He brought grapes, a particular type of riding horse and alfalfa, back to China

The Silk Road was a marvel for merchants and explorers that didn’t have ships. They could get a wagon and make their way from one side of the known world to the other. Its name comes from the fabric that made it famous. Silk was a popular way for Chinese goods to find their way into the rich wardrobes of European nobles. It was also a way to trade ideas, news, knowledge, and culture as much as produce.

Mu Wang’s Mu Tianzi Zhuan provides the first recorded account of the formally established Silk Road travelling from China to Iran and was published around the 5th century BCE. Another early account was a travel report by Zhang Qian, who traveled to Persia and, upon returning to China, laid down the foundations for official relations between these countries (c114 BCE).

Pacific Trade Routes

The Pacific is home to some of the most remarkable sea-going cultures, from the northern waters of Micronesia to the distant tropical islands that flirt with the Melanesian cultures of Papua New Guinea in the Bismarck Archipelago — and from the densely populated Solomon Islands and New Caledonia, venturing into the remote waters of far east Polynesia.

In all this, water and distance are a tightly connected network of cultures related by blood and trade. For example, the Austronesian peoples are the ancestors of today’s Pacific inhabitants, who crossed the seas 3,500 years ago. One only has to look at the pottery to see how trade spread from the islands of South East Asia to the west, through Micronesia and Melanesia, until eventually reaching the distant islands of Polynesia.

The extent of this culture is well recorded in archaeology, even if there are no written records of how trade emerged in the Pacific before European and Asian contact. For example, we know that the Austronesian peoples had traveled to the Indian Ocean as far as Madagascar by 700 CE, being the first to settle this large island off the coast of Africa. We also know that, undoubtedly, they would have interacted with coastal ports in this region and established the first form of trade between Asia and Europe.

However, apart from traveling west, the Polynesians eventually travelled across the great stretch of the Pacific to South America. This is evidenced by their diet, which included the sweet potato, which was not native to Asia or the Pacific. This delicacy quickly became a staple in the Polynesian diet, and one can imagine it would have been a valuable commodity.

Polynesians generally didn’t navigate the Pacific using onboard tools, even if those in the Marshall Islands did. Instead, they could tell where they were due to oral histories and proficient knowledge of the stars. Each island had a guild of navigators to make this task easier to manage.

The recorded interactions with cultures outside of their own are limited before the arrival of European and Asian explorers. They likely made contact not just with the coastlines around South America, the Indian Ocean, and Papua New Guinea but also with Australia and mainland China.

The Earliest Recorded European & Asian Trade with the Pacific

Polynesians have close blood ties to Asia despite several thousand years and vast stretches of ocean dividing up these long-since severed links. Most accept that the Austronesians originated from the Northern Philippines, which was settled by Taiwanese people carrying the technologies of pottery and agriculture from mainland China.

China had been aware of islands and vast stretches of ocean to the east for a long time; however, they had been reluctant to engage in exploration or trade because it was deemed dangerous. In one famous tale of tragedy, Xu Fu, an alchemist who, in 210 BCE, traveled out into the Pacific to search for the elixir of immortality but never returned. So you can understand why they opted to trade with the West and the Islands of South East Asia.

Only after European explorers started to map and record their voyages did the wider world become aware of the rich cultures and lands to the east. But, even if unrecorded explorers had been there well before the fifteenth century, once contact was established, very slowly but surely, the emergence of trade between Asia and the Pacific boomed.

The first Europeans to see the Pacific from the China Sea were António de Abreu and Francisco Serráo in 1512. Then in the following year, Vasco Nunez de Balboa was the first European explorer to sight the Pacific from the Americas. These European explorations would lead to the emergence of trade between Europe and the Pacific that grew gradually over several centuries before it became a bustling market of goods.

In 1520, Ferdinand Magellan sailed across the Pacific Ocean purely for commercial purposes from South America to Asia. Along the way, he landed in Guam, the only non-coastal European settlement in the Pacific for a long time. Although, unfortunately for Magellan, he was killed on arrival in the Philippines, his contact with the Chamorro people was one of the first recorded interactions and example of trade between Europe and the Pacific.

From 1520 to 1565, there was only one way to travel across the Pacific through favorable winds discovered by Magellan. However, Andrés de Urdaneta found a return route, establishing a regular trading route across the Pacific. This lasted as the route taken by trading ships until the time of Captain Cook.

The first European to sight Australia was Willem Janszoon in 1606 as part of the intense competition between trading companies to control trade in the region. Janszoon was employed by the Dutch East India Company and mapped the top of Australia but wasn’t very successful at establishing a trade network.

Other big names in the exploration of the Pacific by Europeans include Abel Tasmin in 1642 (who discovered Tasmania and was the first to see New Zealand) and, of course, Captain James Cook in the 17th century, who completed three epic voyages around the Pacific.

In Conclusion: The World’s Earliest Trade Networks

The earliest trade between Europe, Asia, and the Pacific is a complex history of different civilizations exchanging goods and ideas, from the earliest beginnings of trade between ancient Greece, ancient Rome, and the far East Asian continent, to the more recent connections established between Europe, Asia, and the Pacific. The evidence shows that trade played a crucial role in shaping the world as we know it today, promoting cultural exchange and technological advancement. Studying and understanding the extent of these ancient trade networks is fascinating. However, it should be noted that the available evidence needs to be more complete, and there is still much to be learned and uncovered about the earliest trade between these regions.