Between 1946 and 1989, the United States was locked in a tense period of political tension with the Soviet Union (also known as the USSR). Although there were no direct military conflicts between these nations, giving it the name Cold War, several smaller proxy wars fought between allies of each superpower did occur. There were significant economic effects on the United States due to this four-decade period of heightened military tension and international jockeying for allies and influence. From 1946 to the early 1970s, Keynesian economics led to high government spending that triggered inflation. Then the U.S. shifted to tax cuts and Reaganomics, cutting inflation and resuming economic growth… But resulting in tremendous deficit spending.

Before the Cold War: World War II & Tremendous Military Spending

When the United States entered World War II following the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, it committed its entire industrial production to the fight. Facing both Germany and Japan, the U.S. engaged in full mobilization, also known as total war. Factories went from making civilian goods, such as passenger automobiles, to military goods, like trucks and tanks, virtually overnight. Defense spending soared, rising to as much as 40% of America’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 1945.

After the war ended with an Allied victory, defense spending remained high. One reason was that the US now had to occupy and administrate captured and re-captured territories in western Europe and the Pacific. A second reason was domestic pressure to protect the recently-enlarged defense industry. And third, there remained an ominous potential threat from the Soviet Union. Although the Soviet Union had been an ally during the war, it remained committed to spreading communism internationally. Alarmingly, Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin did not appear to be upholding an agreement to allow nations in Eastern Europe to return to independence.

The Soviets claimed that they needed a buffer zone between themselves and Germany to prevent any future aggression like the infamous German invasion of 1941. Upset at the USSR for refusing to allow Eastern Europe to return to independence, former British prime minister Winston Churchill made a speech in March 1946 declaring that an “iron curtain” had fallen across Europe. This created the popular term for characterizing the divide between a democratic West and an authoritarian, communist East. Tensions heightened further as the Soviet Union helped the communists win the ongoing civil war in China, resulting in China becoming a communist country in 1949.

Defense Spending Remains In Overdrive: Korea, Cuba, Vietnam

As Europe and Asia slowly recovered from World War II and no longer needed direct U.S. military aid and occupation, the growing threat of the Soviet Union and China led to American defense spending remaining high. From 1950 to 1953, the United States fought the Korean War against a Soviet- and Chinese-allied North Korea. North Korea invaded South Korea to unify the Korean Peninsula under communism by force, prompting a U.S. military response. The war ended in a stalemate in 1953, but South Korea’s independence was secured. The aggression of North Korea and China – the USSR did not send troops – helped reinforce the domino theory of communist expansion, which stated that allowing one nation to fall to communism would result in its neighbors falling soon afterward.

After the Korean War, the U.S. aggressively sought to prevent communism’s spread in Asia and Latin America. In 1958, Cuba underwent a communist revolution and brought the dreaded form of government less than 100 miles of America’s shores! The U.S. responded by trying to provoke a popular uprising against Cuban dictator Fidel Castro in 1961 with the infamous Bay of Pigs invasion. The invasion, which involved U.S.-trained anti-communist Cuban refugees, failed, as American air support did not occur, and the islanders did not rise against Castro. The next year, Soviet attempts to put nuclear missiles on Cuba resulted in the Cuban Missile Crisis, where both the US and USSR almost went to war. Fortunately, diplomacy saved the day, and the Soviet missiles were withdrawn from Cuba without shots being fired.

Shortly after the Cuban Missile Crisis, America became embroiled in a growing war in Vietnam. Like Korea, Vietnam had been divided in half after World War II, when Japan had occupied both. In both countries, the communists had been given the northern half of the territory while the non-communists had been given the southern half. In Vietnam, which had been a French colony until 1954, communists were making an effort to unite the entire country under communist rule. As with Korea, the U.S. decided to intervene to prevent the spread of communism. However, the growing Vietnam War quickly proved controversial due to earlier U.S. military assistance to France to help keep Vietnam as a colony, lack of clear success in the war, and lack of clear South Vietnamese civilian desire for U.S. military involvement.

By the late 1960s, hundreds of thousands of American troops were in Vietnam, and casualties were mounting rapidly. There were increasing anti-war and anti-draft protests, and inflation was beginning to rise. Expensive domestic programs put in place by President Lyndon B. Johnson under his Great Society initiatives were competing for funds with wartime spending. At the time, the Federal Reserve chose not to raise interest rates to help fight inflation. This “even-keel” policy made monetary policy less effective, and prices began to rise.

1970s Inflation Puts Keynesian Economics In Doubt

The Cold War contributed to a period known as The Great Inflation, which occurred between 1965 and 1982. Between 1965 and 1973, the U.S. spent heavily on both the Vietnam War and the Apollo Program. Though sometimes seen as separate from the Cold War, the Space Race was indeed a government initiative, sparked by US President John F. Kennedy, to beat the Russians to the moon. Although inflation began creeping up in the late 1960s, even Republicans remained committed to high government spending to boost aggregate demand and keep unemployment low. This school of economic thought, that government intervention in taxes and spending to stimulate the economy is desirable, is known as Keynesian economics and became popular in the 1930s during the Great Depression. Famously, Republican president Richard Nixon said in 1971 that “we are all Keynesians now.”

However, shortly after both the Vietnam War and Apollo Program concluded in 1973, war broke out in the Middle East. On October 6, the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, Israel was suddenly attacked by Egypt and Syria. The resulting Yom Kippur War was brief and saw an unexpected Israeli victory against overwhelming odds. Israel’s military was re-supplied by the United States, while the Soviet Union was supplying the surrounding Arab states. In retaliation for U.S. support for Israel during the brief war, the Oil Producing and Exporting Countries (OPEC) coalition placed an embargo on the U.S. and refused to sell it oil.

The OPEC oil embargo of 1973 sent U.S. gas prices soaring. As a major oil importer, the U.S. could do little to insulate itself from the high global price of petroleum. All petroleum-based fuel rose in price, meaning higher prices for virtually all consumer goods, heating oil, and electricity. Inflation soared, and OPEC kept prices high by keeping output low. Oil prices jumped again in 1979 with the Islamic Revolution in Iran, with Iran’s oil production slashed. Because much electricity and almost all transportation were dependent on petroleum, production costs went up across the board.

Until the oil embargo, inflation had been driven by high demand for goods and services and was known as demand-pull inflation. However, the oil embargo caused prices on goods and services to rise because it cost more to make them and get them to market. This was known as cost-push inflation because the higher cost of production was pushing up prices. Unfortunately, this new type of inflation was more harmful than traditional demand-pull inflation. Demand-pull inflation meant that most consumers had more money to spend, thus driving up prices, but cost-push inflation meant that consumers were subjected to higher prices even though they were not receiving higher pay. In the mid-to-late 1970s, unemployment rose and the U.S. suffered economically from stagflation, which was a combination of stagnant (low or stuck) production and rising inflation as a result of the Cold War.

Reaganomics: Tax Cuts + High Defense Spending

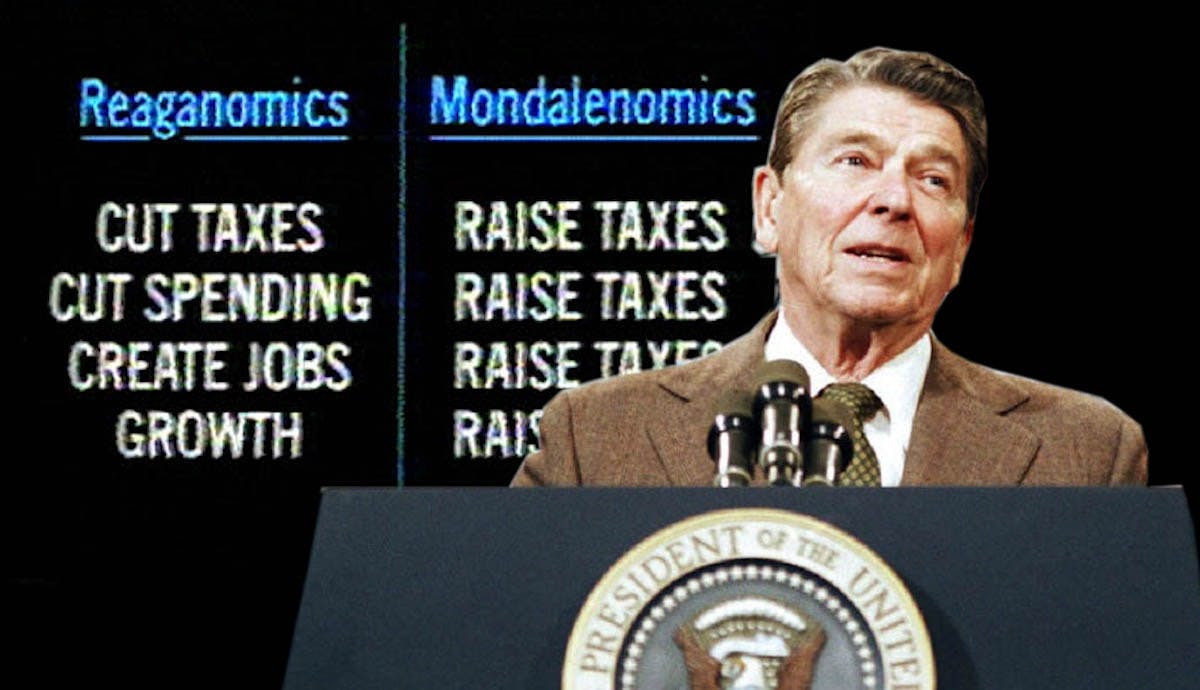

The early Cold War (1946-1973) had resulted in high inflation. By the late 1970s, many Americans had grown critical of high government spending and the taxation it called for. In 1980, Republican presidential candidate Ronald Reagan called for significant tax cuts to stimulate the economy. As Keynesian policies fell out of favor due to the resulting inflation from decades of high government spending, some economists were championing a new school of thought called supply-side economics.

Instead of maintaining high demand through government spending, supply-siders focus on maintaining high supply through reduced taxes and business regulations. Both options result in increased output of goods and services, but increasing supply leads to lower prices. In November 1980, Reagan’s optimistic outlook helped him defeat Democratic incumbent Jimmy Carter, whose popularity lagged due to the weak economy and America’s humiliation in the Iran Hostage Crisis.

However, Reagan did not abandon all of Keynesian theory: He kept aggregate demand high by increasing military spending. Reagan’s mantra was “peace through strength,” meaning that he would prevent Soviet aggression by maintaining American readiness to defend against attacks. To boost defense spending while cutting taxes, there was a substantial increase in deficit spending. To spend more money than was being raised in taxes, the government added to the national debt by selling bonds. During Ronald Reagan’s two terms as president, the national debt almost tripled.

Reaganomics, sometimes described as “trickle down economics,” was successful in restarting economic growth. After the Federal Reserve aggressively raised interest rates to tackle inflation between 1980 and 1982, economic growth kicked in. Reagan won re-election in 1984, touting his econ credentials in his famous “Morning Again in America” political ad. Coming after a slew of controversial presidential administrations, Reagan’s two terms of relative peace and prosperity, coupled with his popular image as a no-nonsense champion of freedom and conservative values, helped make Ronald Reagan a permanent Republican icon.

Fall of the USSR Locks In Popularity of Reaganomics

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev became the new general secretary, or top leader, of the Soviet Union. The relatively young Gorbachev ushered in a new era of economic openness and political reform known as glasnost and perestroika. By the early 1980s, the Soviet Union was suffering from economic stagnation and struggling to compete with the West. At the time, many observers had believed there to be a rough parity between the economic output and military strength of the two superpowers, but this was not the case. The centrally-planned economy of the USSR made it difficult to adapt to changes or produce goods that consumers wanted.

Beginning in the late 1980s, the Soviet Union crumbled swiftly as a superpower. In June 1987, U.S. President Ronald Reagan made a speech at the Berlin Wall where he famously urged his Soviet counterpart, Mikhail Gorbachev, to “tear down this wall!” At the time, the speech received relatively little notice, as it was assumed that the communist governments of both East Germany and the Soviet Union were extremely stable. However, economic problems swiftly eroded the popularity of communist governments, and the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989. Facing domestic protests and economic recession at home, the Soviet government chose not to use military force to keep Eastern Europe under its control.

Under communism, the USSR and its satellite states in Eastern Europe had suffered from supply shortages, worker apathy, and little international trade. When the Soviet Union had enjoyed strong growth before the 1970s, citizens were willing to accept the authoritarian government and lack of democracy. With a failing economy, however, citizens were upset and demanding reform, including access to foreign goods about which they now knew. On December 26, 1991, the Soviet Union officially dissolved and Russia, the largest of the Soviet Socialist Republics, became its successor state.

Ronald Reagan’s amplified defense spending and open challenge to the Soviet Union in high-tech armaments are often credited with leading to the USSR’s crumbling in 1991. Although Reagan was replaced in the White House by his vice president, George Bush Sr., in January 1989, the former California governor is credited with winning the Cold War. His aggressive military spending, including on foreign aid to anti-communist forces in proxy wars, forced the Soviets to attempt to follow suit, which they failed, irreparably damaging their economy.

Post-Cold War: Defense Spending and Deficits Remain Popular

With Reaganomics getting the credit for spending the Soviet Union into submission, tax cuts are today frequently seen as growth-boosters, and deficit spending does not have as negative a legacy as it might otherwise. Although Reaganomics has become more controversial over time, its messaging is still very popular with Republicans today. Economically, tax cuts are seen as a viable tool for growth by conservatives. Most recently, U.S. President Donald Trump ushered in tax cuts in 2017 for all income tax brackets. Although tax cuts are often popular with voters, many worry that such cuts can be inequitable and give larger cuts to wealthy individuals and corporations, lead to increased deficit spending, and result in cuts to important government programs.

Elevated defense spending also maintains a positive legacy due to its importance in the Cold War. With the United States seen as the winner of the Cold War, there is widespread acceptance of the need to maintain a powerful, highly modernized military. Thus, defense spending remains a major component of the U.S. economy, composing almost half of all discretionary federal spending. As of 2020, military spending is roughly 3.7 percent of US GDP.