According to ancient Egyptian belief and language, the world was populated by humans (rmT), the spirits of deceased humans (Ax or mwt), gods and goddesses (nTr), and a host of benevolent and malevolent para-natural entities. The last of these, unlike the previous three entities, was not constrained by a specific Egyptian term and existed on the threshold of the divine and the real world. These entities would be known as “demons.” Knowledge of these Egyptian demons, as well as how to defend oneself from them and employ them to one’s advantage, was crucial to the daily life of the ancient Egyptians.

The Pantheon of Egyptian Demons in Ancient Egypt

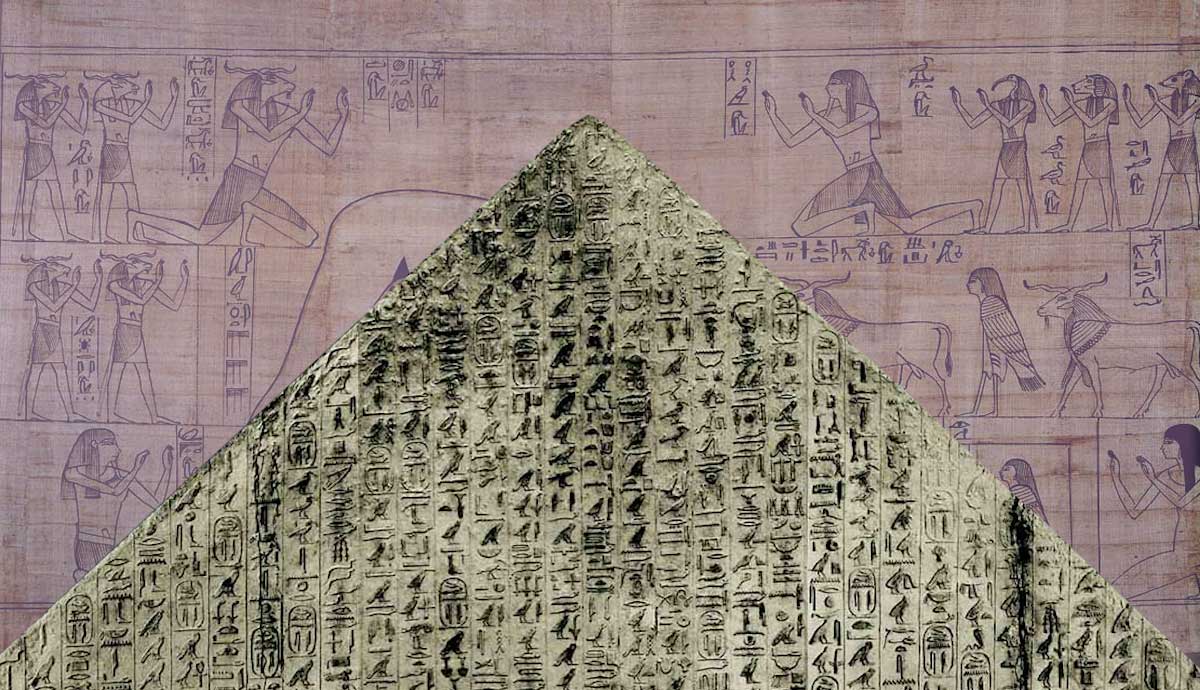

Demonic entities, like the plethora of Egyptian gods and goddesses, numbered in the thousands. According to the Ancient Egyptian Demonology Project, undertaken by Dr. Szpakowska and supporting scholars at Swansea University, over 4,000 demons have been recorded. Unlike the Egyptian pantheon of gods and goddesses, the vast majority of demons did not have temples or cults devoted to them. Instead, demons were featured throughout funerary compositions, such as the Book of Two Ways, Book of the Dead, and the Book of Gates.

It wasn’t until the Middle Kingdom (2030 BCE – 1640 BCE) that Egyptian artists started depicting demons. However, textual descriptions of these entities are believed to have existed in the oldest religious text known to exist, the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649 BCE – 2130 BCE). Despite the plethora of depictions on amulets, wands, and in ancient texts, demons were frequently unnamed. Instead, ancient Egyptians associated demons with a pictorial representation and epitaphs, which can be a description of their appearance or behaviors.

Most importantly, demons were distinguished from each other by the specific illnesses and conditions they brought onto the living and which ones could be used for protection. Often, demons were anthropomorphic in appearance or a human-animal hybrid, ranging from turtle-headed and human-bodied to snake-headed with human arms wielding blades. Numerous demons were even an amalgam between numerous animals in addition to having human characteristics. Although there is no “official” hierarchy among the host of demons identified thus far, demons are believed to have belonged to two different classes.

Wandering-Demons and Guardian-Demons

According to many scholars, Egyptian demons can be divided into two classes: wanderers and guardians. Often held responsible for diseases, misfortune, acts of higher deities, and “things that go bump in the night,” wandering-demons were heavily intertwined with daily Egyptian life. Although wandering-demons often traveled between worlds under the orders of a higher deity, they also acted on their own accord and thus garnered a malevolent characterization. Some of these wandering-demons included Sehaqeq the headache demon (shAqq), He who lives on worms, He who overthrows the cat-fish, and the Emissaries of Sekhmet. As apparent by their epithets, wandering-demons were often the personification of a specific illness and punishment(s).

Guardian-demons were typically affiliated with one of two planes of existence: the netherworld or earth. Often depicted guarding gates, portals, and doors, these demons overlooked entry into sacred liminal places. Guardian-demons can be split into three classes: Doorkeepers, guardians, and heralds. All functioned to protect the purity of sacred places. These demons have titles like: The Hearer (smt.j), Radiant One, and One with a Vigilant Face.

With the sole purpose of protecting their locality from being tainted, guardian-demons were merely performing their duties and were generally not acting on their own accord. As opposed to wandering-demons, guardian-demons did not travel between realms and did not interfere with daily life. However, once an individual reached the afterlife, these demons took on a less-appealing role for the unprepared.

Whether to enter tombs or advance through the gates of the netherworld, an individual generally needed to know the demon’s name, affiliation, and most importantly, to have lived by Ma’at (Truth, Justice, Harmony, Balance, Order, Propriety, and Justice). If the individual did not know the aforementioned things, they would be considered impure, barred from entering, and sometimes have their existence completely eradicated.

Magic, Demons, and Tools

In ancient Egypt, life revolved around the preparation for the afterlife and dealing with the para-natural forces at play every day. With the depiction of demons during the Middle Kingdom (2030 BCE – 1640 BCE) becoming prevalent in art, the ancient Egyptians sought a way to protect themselves, and their loved ones, from the likes of these wandering-demons. Protection from and the harnessing of specific demons would arrive in the form of spells, oracular amuletic decrees (placed inside amuletic papyrus holders), and magic wands. Of these aforementioned forms of protection, magic wands are one of Egypt’s most distinctive magical relics. Fashioned from hippopotamus ivory and embellished with spells that were employed throughout pregnancy and early stages of life, these wands were solely available for the elite (only 230 are known to exist). Additionally, these magical relics were put in the tombs of the departed and protected one’s rebirth. For those who were not privileged enough for magic wands, fixed formulas/spells and symbols could be used for protection against a host of wandering demons.

Gods Associated with Egyptian Demons

Although demons are considered lower entities in the Egyptian pantheon, there are gods and goddesses that are closely linked with both guardian-demons and wandering-demons. Anubis (god of funerary rites) and Thoth (god of sacred texts, magic, and the sciences) both associated with the netherworld, are frequently represented in the company of the guardian demon, Amemet, the Devourer of the Dead. Amemet is always portrayed in a position to consume the deceased if they do not pass Anubis’ scaled judgment after Thoth writes the verdict. However, if one has the necessary funerary composition (and wealth) to confront these tribulations, their heart will never meet the teeth of Amemet. As previously mentioned, despite the terrifying epithet of Amemet, guardian-demons were not generally feared by ancient Egyptians.

Additionally, neither were the gods and goddesses associated with guardian-demons. Certain patrons of wandering-demons, on the other hand, were feared. Daughter of the son god, Ra, Sekhmet, was feared just as much as she was worshipped in ancient Egypt. Often recognized as the bringer of plagues, diseases, and misfortunes, Sekhmet was regarded as a chief patron of the wandering-demons. Throughout numerous funerary compositions and amuletic decrees, spells and formulae were aimed at preventing Sekhmet’s malicious agents from harming them. Sekhmet, on the other hand, was not without redeeming qualities. Because of her connection to medicine and healing, practitioners of medicine made her their patron deity. Though not a demon, Sekhmet is a perfect representation of the duality of demons in ancient Egypt.