Today Emily Carr is a titular name in Canadian art history. She was a well-rounded artist; her watercolors, today on display in all major Canadian museums, are as famous as her autobiographical books. Growing Pains, Klee Wyck, The Book of Small, and The House of All Sorts are now part of Canadian literary programs in many respected universities. They provide us with some important insights not only into the life of this revolutionary and independent artist, but also the society she lived in, and the struggles she faced as a woman painter in Victorian Canada.

A Young Girl From British Columbia

The life and career of Emily Carr were shaped by her inexhaustible need to rebel against any form of (perceived) authoritarianism. As a child, she resented her father’s sternness, despite the influence he had on her upbringing (he was the one who gifted her The Boy’s Own Book of Natural History on her eleventh birthday). A merchant from Kent, England, Richard Carr had settled permanently in Victoria, British Columbia, with his wife, Emily Saunders, in 1863, eight years before Emily Carr’s birth on December 13, 1871. As a teenager, Carr rejected the authoritarianism of her sister Edith, left in charge of the family after the untimely deaths of their mother and father. It was to escape her rule that in 1890 Emily persuaded her guardian to send her to San Francisco to study art at the California School of Design. What she found in San Francisco disappointed her.

Teaching methods were conservative and backward, and she spent three years painting objects and still lifes. She recalls all this in her autobiography Growing Pains (1946), to this day the most important source of information about her life and work. Emily eventually left San Francisco and returned home. Here, for the first time in her life, she gathered a group of children and taught them art classes. Her first studio was a converted cow barn in the backyard of her family home in Victoria.

The village of Ucluelet, nestled on the West Coast of Vancouver Island on the Ucluelet Peninsula, is nearly 300 km (186 miles) from Victoria, Carr’s hometown. The village was built on land occupied from time immemorial by the Yuułuʔiłʔatḥ peoples, members of the Nuu-chah-hulth-aht Nation. For centuries the Western world has known the Nuu-chah-hulth-aht by the name that James Cook adopted for them in 1778 — the “Nootka.” The name they use for themselves translates into English as “all along the mountains.”

Skilled sailors, they used to build their canoes from the huge cedar trees that grew on their island and then set far out to sea, fishing halibut and hunting seals, California grey whales, and humpbacks. The Nuu-chah-hulth-aht were also skilled carvers: their plank-covered houses were embellished with carvings and surrounded by tall, still-standing totem poles. Emily Carr first saw the Nuu-chah-hulth-aht poles when she traveled to Ucluelet in the late 1890s. This was her first contact with the First Nations of British Columbia and their art.

A Young Girl From British Columbia Lands in Europe

In 1899, Carr landed in Europe to study in London, England. It was her first trip outside of North America, and the Westminster School of Art left her disappointed. What she was taught fell into the category of the conservative tradition of the 19th century.

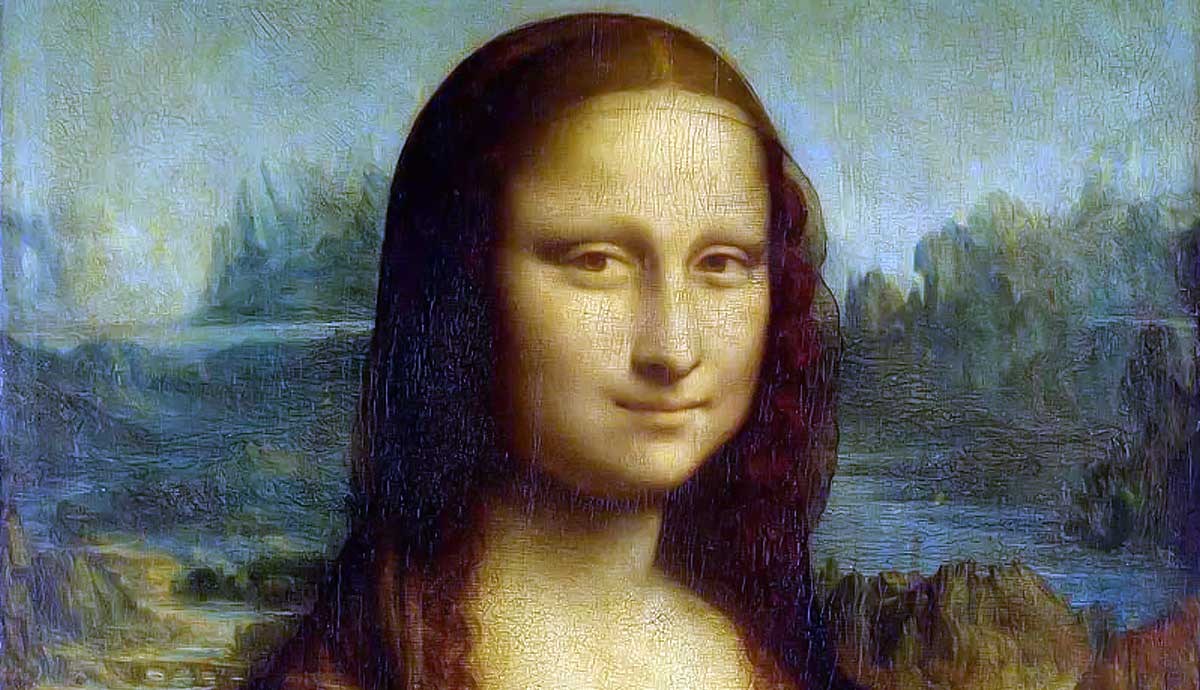

Over the years, Carr often expressed her dislike for the London art scene. However, she loved Paris. In 1901 she traveled to the French capital. During her twelve days there, she visited the Louvre and immersed herself in the revolutionary artworks of Impressionism, Fauvism, and Post-Impressionism. She was struck by the beauty and modernity of painters such as Claude Monet (1840-1926), Henri Matisse (1869-1954), and Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890). The works of art she saw in Paris were nothing short of a revolution for her.

Back in England, she spent the next eight months in St. Ives, Cornwall. In the literary world, St. Ives is often celebrated as Virginia Woolf’s lost Eden. Between 1882 and 1894, Woolf spent every summer with her brothers and sisters in St. Ives, in the large white house rented by her parents. Across the bay from Talland House is Godrevy Lighthouse, which influenced Virginia in writing one of her most powerful and beloved novels, To The Lighthouse (1927).

Emily Carr arrived in St. Ives just seven years after the Stephen family had stopped renting Talland House. In Cornwall, Carr was encouraged by Julius Olsson (1864-1942), a leading figure of the British Impressionist movement, to draw en plein air, on the Cornish beaches surrounding St. Ives. But she didn’t. She preferred the shadows and light tricks of Tregenna Woods.

Her first European interlude came to an end with her hospitalization at the East Anglian Sanatorium in 1903. She returned to British Columbia in 1904. Carr went to France again in 1910 and enrolled at the Académie Colarossi: this time she stayed in Paris for more than a year.

In the works she produced during this period, we can clearly see that her style had evolved into that of her later works. In the dense, dynamic colors of Autumn in France (1911), now at the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, and Le Paysage (Brittany Landscape), painted that same year, we can already see the shapes and textures of Indian House Interior with Totems (1913). In Paris, she befriended English artist Harry Phelan Gibb (1870-1948), a friend of Matisse (1869-1954), and Gertrude Stein (1874-1946). It was Gibb who encouraged her to pursue what is now known as her “First Nations project.”

Sister and I in Alaska

The trip Carr made with her sister to Alaska in 1907, represents one of the great turning points of her career (and perhaps her life). Nearly ten years separate this trip from the first she made to Ucluelet, on Nuu-chah-hulth-aht lands, and Carr chronicled it extensively. She drew sketches, with long notations about each drawing in her notebook.

It was in Sitka that she first saw the totem poles of the Haida and Tlingit peoples, depicted in her Totem Walk at Sitka. The composition is traditional, clearly influenced by the techniques she learned in London. Despite this apparent simplicity, Carr manages to infuse mystery into a rather simple scene. With their bright colors and imposing height, the Haida and Tlingit totem poles stand out among the trees in all their majesty.

15 of them were transported to the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904 and attracted huge crowds. Alaskan Governor John Brady had them erected outside the Alaska Pavillion. By the end of the fair, thirteen of the 15 totem poles had returned to Alaska. They reached Sitka two years later, in January 1906, and some of them can be admired today in Sitka National Historical Park.

It was after seeing the Haida and Tlingit totem poles at Sitka that Carr decided to portray and document the artworks of what she considered a dying race, decimated by smallpox, measles, and whooping cough, whose glorious past, testified by their majestic artworks, was but a distant memory. After her second 15-month-long stay in France, Carr returned to Canada in 1911, more determined than ever to work on her First Nations project.

A Dying Race?

In 1912, Carr undertook several excursions along the Northwest Coast. She traveled to Haida Gwaii, an archipelago of islands and islets off the northern coast of British Columbia, which at the time was known as the Queen Charlotte Islands. She traveled north along the coast, where she encountered the northernmost First Nation of the area, the Tlingit, whose lands stretched as far north as Yukon and Alaska.

Here, she also spoke with the Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw peoples, who showed her their artworks and welcomed her into their houses. By the early 20th century, the Haida, who had lived on these islands since time immemorial, had already been decimated by epidemics, and their customs had been altered by the introduction of European goods and foods. It is easy to understand why Carr considered them a dying race, bound to disappear.

She was not alone in her beliefs. The colonization of North America and the theft of land at the hands of white settlers tended to be justified by the so-called “vanishing Indian” theory. According to this theory, Indigenous peoples were essentially a dying race: Indians, as they were called in the 18th and 19th centuries, could not survive the advent of the “more civilized” and “advanced” white race.

The vanishing Indian doctrine, which closely resembles the Australian doomed race myth, was backed by an interpretation of the Darwinian evolutionary theory: Just as it happens in the natural world, where the stronger wins and the weaker perishes, the demise of an uncivilized race upon contact with the more advanced European civilization was considered inevitable.

The derogatory and pitiful terms used to describe Indigenous peoples in the press and in books served to reinforce the vanishing Indian theory and to portray the doom of Indigenous peoples as an ongoing process that was impossible to stop. At the height of the Colonial Period, First Nations were described as primitive, lazy, child-like members of an inferior race who could not be trusted. Because of their backwardness, they were not worthy of owning or managing their land, unlike white settlers.

The doomed race and vanishing Indian theories effectively paved the way for the legal application of the doctrine of terra nullius (from the Latin term, “nobody’s land”). This doctrine did not deny the existence of Indigenous peoples; their presence was indeed recognized, but their property rights were denied because they had allegedly failed to exploit their bountiful lands for economic purposes.

The North American and Australian continents were open to European conquest and settlement. Since agriculture was considered the prerequisite for civilization, it was the white man’s duty (and burden) to properly use and exploit the land.

As evidenced by her writings, Emily Carr believed in the myth of the vanishing Indian. This does not mean, however, that she considered Indigenous peoples backward, lazy, or primitive. She could not — the wonderful artworks she encountered during her trips testified to a highly sophisticated culture, with its own religious beliefs and values. They were different from those of the Europeans but certainly not inferior.

It is worth noting that most of the watercolors Carr produced in the years 1911-1913 are devoid of human beings. Such is the case with Tanoo, Q.C.I (1913), now in the Royal B.C. Museum. The only sign of life in the smallpox-ravaged village of Tanoo are three tall totem poles.

While it is true that Carr focused her attention primarily on Indigenous art and less on the men and women who produced it, there are some exceptions. In Potlatch Figure (1912), Cumshewa (1912), Indian House Interior with Totems (1913), and War Canoes (1912), for instance, Carr portrays men and women in their daily lives. Standing in front of their carved houses, huddled under totem poles or around their painted sea-going canoes, they are here to highlight the majesty of Indigenous artworks. They’re tiny and difficult to distinguish against the lush background. Yet they are part of it.

Carr quickly realized that the lives and cultures of Indigenous peoples were inseparable from the lush forests and waters of the West Coast. Throughout her life, she repeatedly expressed her admiration for their ability to live off the land, to use every part of the cedar, for instance, as well as every bit of the animals they hunted and the fish they caught.

Emily Carr and the Group of Seven

In 1913 Carr exhibited two hundred of her works in Vancouver. In her Lecture on Totems, which she delivered at Dominion Hall and in the letters she sent to the minister of education in British Columbia, she expressed her deep admiration for the First Nations of the Pacific Northwest Coast. She also expressed what we now perceive as a typically white and paternalistic desire to preserve their culture.

Despite her unconventional nature, she was, after all, a woman of her time. Her exhibition in Vancouver received mixed reviews. For the next ten years, she considered her career a failure and isolated herself in her “House of All Sorts” on Simcoe Street, in Victoria. It took 14 years for the Canadian art world to acknowledge this great painter and her works.

In 1927, Eric Brown, director of the National Gallery of Canada (which to this day hosts some of her most important works, such as Blundern Harbour, Cumshewa, and Potlatch Figure), invited Carr to present her works at the major Exhibition of Canadian West Coast Art: Native and Modern. He also introduced her to the Group of Seven.

This was a new beginning for Carr, the start of a new phase in her life and in her career. Her friendship with Lawren Harris (1885-1970) was a cornerstone of this new phase. In the years that followed, her works were included in group exhibitions first with the Group of Seven and later, in 1938 and 1939, at the Tate Gallery in London and then in New York. By now Carr was beginning to be recognized as one of the most influential names in Canadian art history.

In 1930, during a trip to New York, she had the opportunity to see the works of Pablo Picasso (1881-1973), along with those of Georges Braque (1882-1963), and Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944). She also met and befriended revolutionary artist Georgia O’Keefe (1887-1986). She poured all these influences, especially Cubism and the works of Bertram Brooker (1888-1955), into her late works.

Initially concerned mostly with Indigenous art and culture, she later began to depict almost exclusively the rugged landscape of British Columbia. Humans (including Indigenous peoples) are absent in her later watercolors.

In 1929, Carr took another trip along the west coast of Vancouver Island. This time she visited the village of Yuquot and the community of Mowachaht-Muchalaht that lived there. Nearly 500 years earlier, in 1778, James Cook had first landed at Yuquot (then at its original location on Nootka Island), during one of his first encounters with the First Nations of the Pacific Northwest Coast.

Shortly after this trip, Carr painted her Church in Yuquot Village. Against the backdrop of a dark green forest stands the small Catholic white church of Yuquot, solitary, windowless, but imposing. Her friend Lawren Harris liked this painting very much; he bought it and hung it in his house, not before having it included in the National Gallery of Canada’s Fifth Annual Exhibition of Canadian Art of 1930.

The title Carr had originally chosen for her watercolor, however, was Indian Church. Only in 2018 did the Art Gallery of Ontario, where the painting is now on display, decide to rename it. This decision sparked a series of debates. Accusations of whitewashing were made. What matters in the end is that it was done in consultation with the traditional owners of the land on which Yuquot Church was built.

Her most emblematic work from this period is Vanquished (1930), now exhibited at the Vancouver Art Gallery. Here Carr depicts an abandoned Indigenous village. It is a scene shrouded in silence, a scene of desolation, abandonment, and decay. The painting possesses a dreary, elegiac quality that some have interpreted as a sign of Carr’s belief in the vanishing Indian myth.

More simply, however, she might have depicted a scene she herself had had the chance to witness several times during her trips along the Pacific Northwest Coast. Native communities, decimated by epidemics, often moved to bigger villages, leaving their wooden houses and glorious totem poles to rot and decay. In the same years, Carr also focused her attention on the effects of deforestation both on the landscape of British Columbia (at that time increasingly littered with rotten stumps), and on the lives of its Indigenous communities.

While some post-colonial critics view this latter phase of her career as perpetuating an idea of national identity built on the absence of First Nations, others have seen Carr’s attention to Indigenous art and artifacts as a kind of personal resistance against that very idea of cohesive national identity sponsored by colonial institutions. As Linda Morra writes in her essay Canadian Art According to Emily Carr, “Carr is engaged in a situation, a cultural double bind, as it were, that effectively ties her artistic hands. What she writes or paints about will never be deemed appropriate in our period.”

In 1933, eleven years before she died in 1945, Carr bought “the Elephant,” a caravan she converted into her home. It allowed her to continue to paint en plein air in the forests near her hometown of Victoria, in Metchosin, Albert Head, and Goldstream Park.

Where Can I See the Works of Emily Carr?

Today, Emily Carr’s watercolors are displayed in museums and art galleries across Canada. In Ontario, they can be seen at:

- National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Kleinburg

- Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto

- Art Gallery of Hamilton, Hamilton

In British Columbia, her works can be found at:

- Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, Victoria

- Royal BC Museum, Victoria

- Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver

- Audain Art Museum, Whistler