Emmanuel Levinas was an influential French philosopher. His two most pronounced philosophical influences were Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. Levinas’s philosophy takes up Husserl’s phenomenological method, but the problems he addresses—and his conception of philosophy’s immediacy and enmeshment in life—are drawn from Heidegger. As such, in order to find our way into Levinas, it is necessary to map the ways in which he is strongly influenced by these two thinkers, as well as his crucial divergences from both of them.

Ultimately, despite considerable borrowings from both thinkers, Levinas’s emphases on escaping from the finitude of our bodies and on the ethical responsibilities that come with encountering the face of the Other are most striking in the ways they transform the problems and questions inherited from Husserl and Heidegger.

Emmanuel Levinas’ Influences: Husserl’s Phenomenology

From its very outset, Levinas’s philosophy is grounded in Husserl’s phenomenology. Levinas’s thesis, The Theory of Intuition in Husserl’s Phenomenology, was published In 1930 and focused on Husserl’s theorization of the conscious subject and his notion of intentionality.

For Levinas, as for Husserl, it is essential that the world we encounter has immediate, pre-analytic meaning for us as subjects encountering it. This meaning is a constellation of desires, plans, anticipated futures, and imagination. In short, subjective experience finds the “actual world” constituted by all manner of properties and possibilities that proceed from consciousness, according to the subject’s interests and specific attentions.

Intentionality, meanwhile, is used by Husserl to describe the ways in which thought and perception are directed towards things, or are about particular things, in a way that goes beyond the names that denote those things, or specific sense-perceptions.

What Husserl stresses is that the intentionality of thought and experience are prior to the more general kinds of judgment we might go on to make. In other words, a directed, specific perception of and thought about a particular chessboard precedes any general proposition I might make about chessboards—thought and perception always have this aboutness. As Charles Siewert puts it in his article “Consciousness and Intentionality” (2022):

“Husserl holds that the sort of judgments we express in ordinary and scientific language are founded on the intentionality of pre-predicative experience, and that it is crucial to clarify the way in which such experience underlies judgment.”

Levinas takes both the idea of intentionality and Husserl’s strong emphasis on the priority of pre-analytic meaning in experience and integrates them into his philosophical project.

However, for Levinas, Husserl’s phenomenology is fundamentally too detached, too intellectual in its conception of the subject. For Levinas, embodiment is essential to our experiences of ourselves and others, constituting both the tragic limit that we must transcend and the most basic ethical encounter.

What Levinas finds in Heidegger is the kind of engaged, incarnated philosophy that Husserl’s cool detachment lacks.

The Tragedy of Finitude

Philosopher Simon Critchley’s series of lectures, The Problem with Levinas (2015), frames Levinas’s work as an attempt to solve one central problem. The problem in question, which Critchley calls the “tragedy of finitude,” is a fundamentally Heideggerian problem, and concerns the fact of our attachment to ourselves.

This attachment, which at first sounds truistic and perplexing as a basis for writing philosophy, needs some explanation. First, Levinas draws upon the Heideggerian notion of “thrownness,” i.e., the fact that we experience ourselves as being thrown into a world, a world that is already in motion, full of constraints and contracts that we are involuntarily thrust into. When we are born, all kinds of things that surround us are already in place, and are neither constructed by nor immediately malleable to, our will. In being thrown into the world—a world which we always have to encounter not as some neutral outsider or observer, but as participants—we encounter a kind of finitude: there are limits and confines that regulate our wills.

This thrownness leads us to the core of finitude and of our tragic attachment to ourselves, which is the gap between the “I” and the self. If the “I” (in Levinas’s French, the moi) is the marker of the conscious, infinite, subjective will, the active self, then the self (or the soi-même) is the passive, finite person and body with which the will is inextricably bound up.

The tragedy, then, lies in the ways in which the self inhibits and limits the force and freedom of the “I.” It is not just that we are thrown into the world without our consent, but that being in the world means being anchored to a stable, finite self, with a finite mortal body; we are awkwardly stapled to bodies and selves that constantly thwart the impulse towards pure subjectivity, towards a kind of pure, intentional mastery over things.

Husserl’s phenomenology is certainly concerned with the identity and tension between the subjective and the objective self, but where Levinas leans heavily on Heidegger is in framing this identity, and the finitude it imposes upon the subject, as a tragedy.

Critchley argues that finitude is tragic for Levinas, as it initially appears for Heidegger, because, unlike Husserl, Levinas conceives of philosophy as being immediately and consumingly important for living in the world. On this view, Husserl seems to conceive of philosophy and phenomenology as distant, theoretical, and academic in the fullest sense, rather than as something pressing and vital. Levinas takes this idea from Heidegger, for whom being thrown into the world is viscerally terrifying, and for whom being anchored to a finite self is not abstract but rather crushingly claustrophobic.

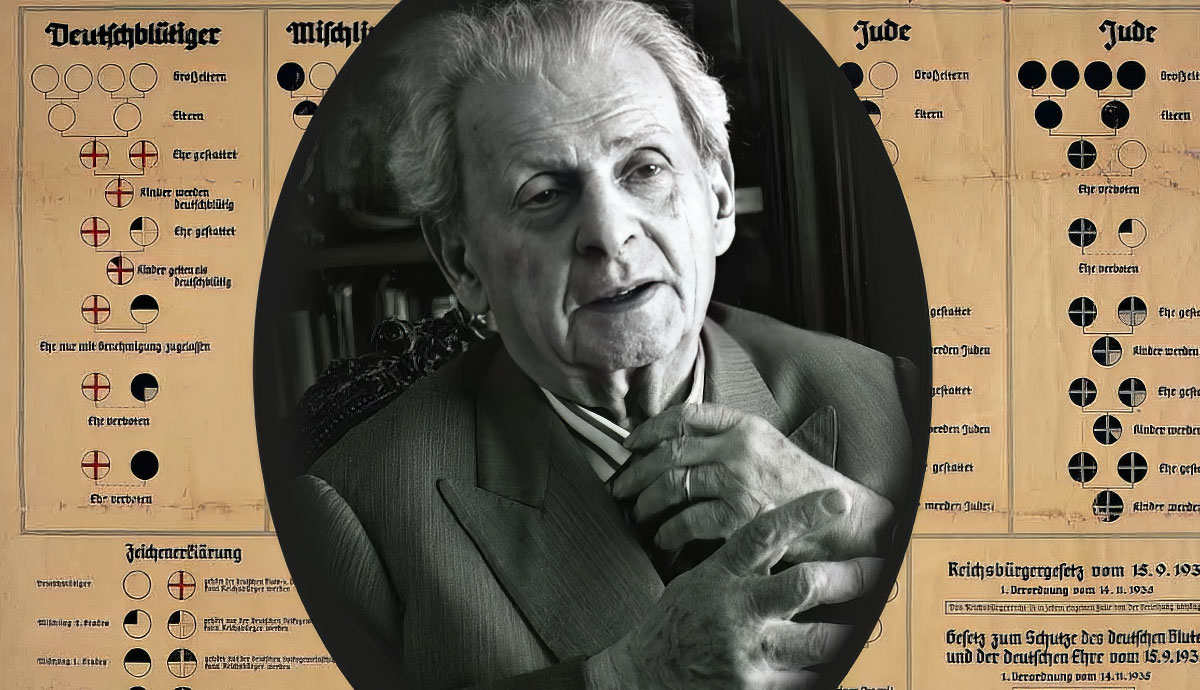

Heidegger and Fascism

Heidegger’s contribution to Levinas’s thought is substantial, and, therefore, deeply fraught. The enormous importance of Heidegger to the way that Levinas conceives of the purpose of philosophy, the nature of being, and our attachment to our bodies is constantly undercut and problematized by Heidegger’s notorious association with Nazism.

Levinas seldom addresses this association, and its implications for his philosophy, directly, but his essay on “Hitlerism” functions as a powerful defense of Levinas’s against accusations of fascist underpinnings, and—while Heidegger’s name appears nowhere in the essay—as an excoriating critique of the latter’s fascist solution to many of their shared philosophical problems.

“Reflections on the Philosophy of Hitlerism” appeared originally in the leftist Catholic journal Esprit in 1934, and embeds Levinas’s critique of fascist thought in his wider philosophical project, treating the Nazi obsession with race and blood as an attempt to embrace, rather than escape, the tragedy of finitude. The essay also, however, analyses fascism as an effective and devastating critique of liberal political philosophy; fascism highlights the complacent delusions of liberal thought, and its attempts to ignore or deny embodiment and finitude.

The tragedy of finitude, for Levinas, is that the subjective “I” is anchored to all the things that make up a person in the world, not just a body in the simplest anatomical sense, but a self, possessed of history, nation, mortality, impotence.

In short, finitude is a collection of limits that impose upon what we might will ourselves to do, embody, and perceive. “Hitlerism” is, in Levinas’s analysis, an attempt to circumvent the inherent tragedy of this predicament not by getting out of it, but instead by embracing the very things that limit us as subjects. Thus, the Nazis celebrated bloodline, nation, race, and physicality above all else.

Where Levinas sees an urgent need for some kind of transcendental escape, the fascist sees something to inhabit—to use the appropriately Heideggerian terminology, to dwell in.

Emmanuel Levinas on Liberalism

The critique Nazism offers of liberalism, meanwhile, is found in its provision of an alternative to liberal irony. Where the liberal response to finitude offers a kind of ironic detachment of the subject from the self, Nazism counter-proposes a sincere, triumphal sincerity. In Critchley’s words:

“In a world of ironists, liberals, and aesthetes, in a world of kitsch and the baroque, in our world, we crave authenticity, something serious and committed, and that’s what fascism offers. Never forget that. Hopefully you haven’t all just become fascists.”

Simon Critchley, The Problem with Levinas, 2015

Liberalism, as a political position, corresponds to the detached, disembodied conception of the subject so familiar from Descartes. The cartesian ego, the “I” who thinks, is only ever an “I” and never a self. By the same token, Levinas criticizes liberalism for its delusional fantasy of a discarnate subjectivity, of a self that is not tragically finite. Nazi ideology is so seductive, Levinas suggests, because it not only acknowledges but celebrates the difficult fact that the ego is really attached to a particular, embodied self.

Levinas, however, proposes that rather than coming to terms with finitude, or embracing it, what we must do is escape it. Contra Heidegger, Levinas’s approach in On Escape (1935) is to focus on the particular sensuous and physical states that make our intentional selves feel trapped in our embodied selves, and to theorize ways of remedying and transcending these states. In Levinas’s later work, transcendence becomes more explicitly religious as a project, but in any case, he pursues a way out of finitude and into a transcendental infinity, whether secular or theological.

In the end, then, Levinas’s philosophy gains its distinctive character precisely from its split with Heidegger, a split which is deeply bound up in Heidegger’s embrace of Nazism, and Levinas’s horrified rejection of it. In rejecting Heidegger’s racialized solution to the tragedy of finitude—this apparently insurmountable condition of being bound to ourselves and our bodies—Levinas not only puts distance between himself and the suspect progenitor of his philosophical approach, but carves out for himself a novel and powerful position on transcendence and politics alike.