What was it that compelled Emperor Commodus, a product of Rome’s so-called “Golden Age,” to turn his back on the examples offered to him by his immediate predecessors, and instead look to the madness and might of Hercules? Son of Marcus Aurelius, he inherited power and became the first emperor raised to rule. His obsession with Hercules led him down a treacherous path, blurring the lines between reality and myth. From gladiatorial combat to shameless self-proclamation as the Roman Hercules, Commodus left a legacy of audacious indulgence that both fascinated and repelled his subjects.

Commodus and Imperial Immitation

In ancient Rome, it wasn’t uncommon for a new emperor to look for a role model, some former ruler or powerful figure, who could inspire them to achieve great things. During the fourth century, for instance, the Roman senate would harken back to halcyon days and salute their new rulers with an appeal to the past: “Be more fortunate than Augustus, and be better than Trajan!” However, not all emperors were wise enough to choose either the first and most long-lived princeps, or indeed the optimus princeps (“best emperor”) as inspiration. Sometimes, different role models were sought for political reasons.

Having seized power after a particularly lengthy and bloody series of civil wars, the Emperor Septimius Severus reputedly attempted to terrify the senate into subservience by praising the memory of Sulla and the bloody cruelty of the proscriptions he launched against his enemies. Later, Severus’ son, Caracalla, would masquerade as a soldier, eschewing (though only sometimes) the life of imperial luxury for the manual labor of the legionaries. Caracalla was not the first emperor to shun the traditional behavior expected of the empire’s most important citizen, with Nero having nurtured fantasies of fame for his dramatic skills.

By and large, these attempts at imperial emulation were roundly failures. Whether the emperors set their sights on the lofty heights of matching a celebrated predecessor, or they simply charted a different course, their decisions often resulted in the alienation of the main groups upon who they relied for support; namely the senate and the soldiers. One of the most infamous of all these imperial delusions, and perhaps the most bizarre, was the Emperor Commodus and his Herculean pretensions.

A Golden Age? Raising Commodus

At the time of his accession as sole emperor in 180 CE, Commodus was unique in the history of the principate. Although imperial power was de facto dynastic, for myriad reasons, no reigning emperor had ever previously had a son raised to be emperor. Perhaps the closest the empire had come had been during the Flavian dynasty in the second half of the 1st century CE. Vespasian, the victor in the civil war known as the Year of the Four Emperors (68-9 CE), was survived by two adult sons — Titus and Domitian — who both became emperor.

In fact, after Domitian’s downfall, the succession had been organized by adoption. A series of emperors who did not have children each passed the imperial power to a nominated successor who was adopted into the ruling dynasty: from Nerva, to Trajan, to Hadrian, then Antoninus Pius, and finally Marcus Aurelius. This period of Rome’s history would be remembered as a “Golden Age,” a characterization that has remained particularly enduring in part thanks to Edward Gibbons’ characterization of this era. The perception of a “Golden Age” was in large part a result of the smooth transition of political power from one emperor to his adopted successor, as well as undue influence attributed to the more benign characteristics of certain emperors from this period, such as Marcus Aurelius’ philosophical interests.

Commodus changed all this, however. The marriage of Marcus Aurelius and Faustina the Younger was to prove particularly fecund: together they had 13 children, including Commodus. Commodus was recognized as his father’s heir from an early age, not least in response to the broader political instability of the period (which should again temper suggestions of a “Golden Age”). In the north of the empire, there was war on the Germanic borders, while in the east, Marcus’ former ally Avidius Cassius — a leading figure in the Parthian War — had attempted an abortive revolt. The war in the east also brought a devastating pestilence – known as the Antonine Plague – back to the Roman Empire.

When his father made the decision to begin communicating Commodus’ position as his heir, it made the young man something hitherto unique in Roman imperial history: he was the first porphyrogennetos emperor. This meant, literally, that he had been born into the imperial purple. His near contemporaries recognized the uniqueness of Commodus’ situation. Herodian presents him delivering a speech to the Roman soldiers shortly after Marcus’ death in 180 CE, in which the new ruler described himself as “the only one of your emperors to be born in the palace… the imperial purple lay waiting for me the moment I was born.” From this seemingly auspicious start, the reign of Commodus would quickly unravel…

Hero Worship: The Cult of Hercules in the Roman Empire

Whether known by the Greek “Herakles” or the Latinized version “Hercules,” there are many characteristics usually associated with perhaps the most famous hero from Greek mythology. This might range from his divine father, Zeus, to his famous labors, including the slaying of the Nemean Lion and the cleaning the Augean Stables. One thing that may not necessarily spring to mind immediately are his travels. However, in the course of his adventures and labors, Hercules traveled far and wide around the Mediterranean world. Legacies of this itinerant hero are still felt today. The Pillars of Hercules which flank the Strait of Gibraltar, for instance, are the rocky promontories that mark the westward limits of Hercules’ travels (which he reached undertaking his 10th labor, fetching the Cattle of Geryon). The hero’s wanderings also took him across the Italian peninsula and, from there, into the mythology of the Etruscans and the Romans.

Hercules even features in the foundational myth of Rome. According to Book VIII of Virgil’s Aeneid, the growth of the cult of Hercules can be attributed to the hero saving the people of Latium. Long before the city of Rome was founded, the people of Latium were being terrorized by a fearsome fire-breathing giant, Cacus, a son of Vulcan.

Cacus had been eating the local people and he had also stolen the cattle of Geryon. Hercules was responsible for not only freeing the cattle but also for saving the Latins from the giant. Hercules set up an altar where he had slain the giant, which can be linked to the Ara Maxima, in Rome’s Forum Boarium, the ancient Cattle Market. Today, the remains of ancient devotions to Hercules are still visible, most conspicuously, in the circular Temple of Hercules Victor. In the centuries that followed, the myth became a common subject in artistic depictions of Hercules, imagined by figures such as Dürer and Frans Hals, while a colossal sculptural depiction by Baccio Bandinelli dominates the entrance to Palazzo Vecchio in Florence.

There is diverse evidence for the worship of the cult of Hercules in Rome and across the empire, and new discoveries regularly emerge. The demigod’s celebrated labors and eventual deification, as well as his strength and courage, made him an aspirational figure in the ancient world. Alongside the great temples to Hercules erected at Rome and around the empire (such as the colossal Temple of Hercules in Amman, Jordan), the importance of the demigod is evident in his representation across a variety of other media. These range from sculptural masterpieces, such as the Farnese Hercules, a copy of which once stood in the Baths of Caracalla, through to the rustic imaginings of the hero on provincial altars.

Imperial depravities: Commodus, the “Bad” Emperor

Despite being the son and heir of perhaps the most celebrated of all Roman emperors, Commodus is today remembered as one of Rome’s worst tyrants. The main historical sources that detail his life and reign — mainly Cassius Dio, Herodian, and the Historia Augusta — are all roundly critical of the emperor. Often, these criticisms reflect the concerns of the historians themselves.

For the senator Cassius Dio, for instance, the focus of his invectives against Commodus centers on the emperor’s treatment of the empire’s traditional political elite. Dio railed against the way Commodus rejected the example set by his father. Dio claims that Marcus had provided his son with a series of trusted senators — the “best men” in the empire — to provide guidance for his son. However, much like that other archetypical bad emperor, Nero, Dio narrates how Commodus withdrew into a world of sycophancy and license, with the emperor coming under the influence of less scrupulous figures at court.

Several abortive plots were launched against him, including one in which the main conspirator — Claudius Pompeianus — attempted to strike Commodus down. As he brandished his sword, he shouted at the emperor, “See! This is what the senate sends you!” Perhaps unsurprising, the conspiracies against him seemed to push Commodus even further away from a functioning relationship with the senate.

Other accounts instead present an emperor who almost begins to resemble a caricature, the living embodiment of imperial vice in all its varied forms. The Life of Commodus in the Historia Augusta (always a source rich in scandal if not so much verifiable fact), delights in regaling the reader with evidence of the emperor’s degeneracies. These range from sexual debaucheries, including rumors of incest with his sister (a knowing nod by the author, perhaps, towards that other archetypal bad emperor, Caligula), to cruelty and the downright disgusting: “It is claimed that he often mixed human excrement with the most expensive foods and he did not refrain from tasting them … ”

Megalomania (i): Commodus the Gladiator

Physical prowess was an important factor in shaping attitudes towards rulers in ancient Rome. Not for nothing does Suetonius’ biography of Caligula begin by lauding the exercise regimen of Germanicus, the juxtaposition used to heighten the reader’s appreciation of Caligula’s failings. It seems, from several sources, that Commodus himself was an imposing specimen. Being well-proportioned according to the Historia Augusta, the son of Marcus Aurelius seems to have dedicated significant time to exercise and training; Herodian records that people who witnessed the emperor sparring were impressed by Commodus’ prowess as an archer and with a javelin. However, whereas Germanicus was lauded for using exercise to better himself, for Commodus, the training became a means to only further distance himself from the expected behavior of an emperor.

The crucial factor was that Commodus allowed his training to spill over into the public eye. Commodus was the infamous gladiator emperor (as made famous by Joaquin Phoenix in the 2000 blockbuster, Gladiator). The decision of the emperor to take to the arena was incredibly subversive. Spectacles, including gladiatorial combat and chariot racing, were highly politicized in the Roman world, allowing aristocrats in the empire and the emperors themselves used to convey power and to cultivate support. But the emperor’s decision to take an active role in the entertainment itself offered a new paradigm and it provided a new idiom for visualizing imperial power. Specifically, it was closely wrapped up in the personal attributes of the emperor: strength, athleticism, and martial prowess. It was, in part, successful: Commodus’ marksmanship and combat prowess in the arena was popular among the Roman mob according to Herodian.

However, Commodus’ attempt to provide a new paradigm for understanding imperial power alienated the Roman elite. Cassius Dio’s contemporary account of the years of Commodus’ reign is scathing, with the historian noting that — were it not for the simple fact that it was the emperor himself degrading his station — then there would be no cause to record such indignities. From Dio’s narrative, it appears that the senate’s presence at Commodus’ gladiatorial bouts were used as a way for the emperor to publicly assert his control over Rome’s elite: the senators in attendance were commanded to shout: “you are lord.”

Intriguingly, the historian also suggests that the Roman populace themselves were actually reluctant to enter the arena, an interesting contrast to Herodian’s account. Perhaps, this is the senatorial historian highlighting Commodus’ universal unpopularity to offer an early justification for the coup that would eventually depose the despotic emperor…

Megalomania (ii): Commodus as Hercules

The gladiatorial dimension was not the only new paradigm for representing imperial power adopted by Commodus. Hercules provided Commodus with a further means of expressing his individual status, equating the emperor with the demi-god and hero, and his associated virtues. Specifically, the link to Hercules also connected Commodus to the Roman pantheon: Hercules was the son of Jupiter, the chief Roman god. It is important to recognize that, although the narrative sources are again highly critical of Commodus’ overt and explicit posturing as Hercules, it was rooted in imperial precedent. His predecessors throughout the second century CE had all been associated with Hercules, just to lesser degrees. This was even the case for Trajan, the so-called optimus princeps. Pliny the Younger’s panegyric of the emperor likened his military exploits to Hercules’ labors.

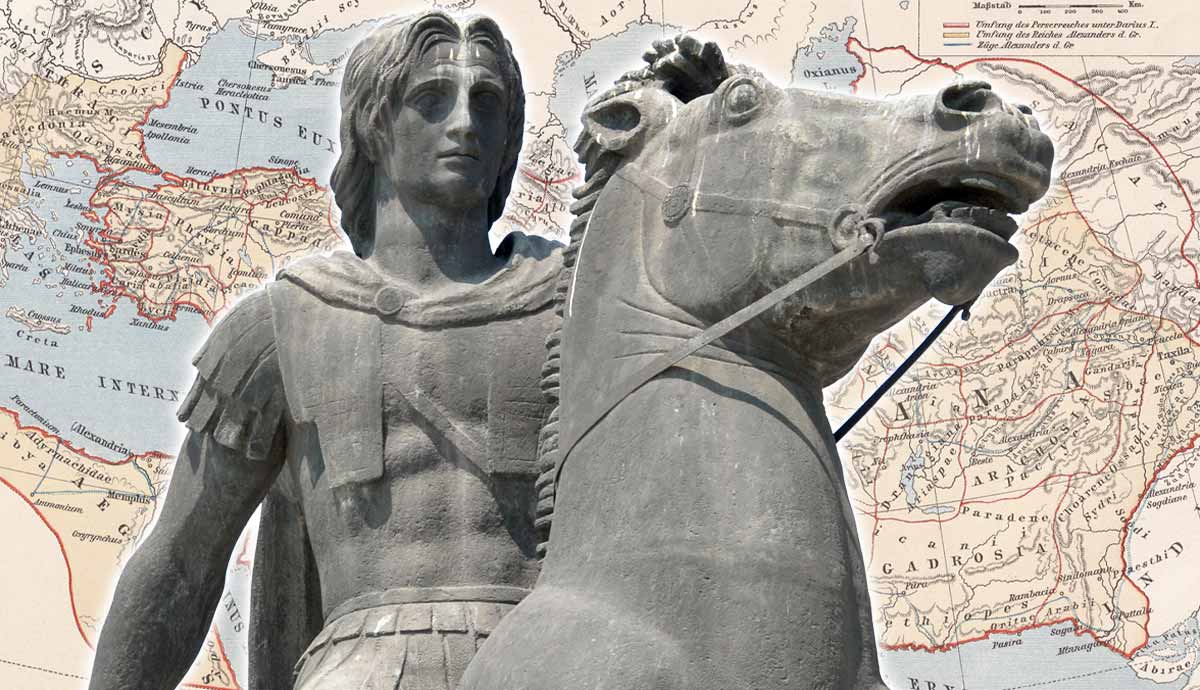

The principal problem appears to have been the extent to which Commodus asserted his link to the demigod and hero of myth. According to Dio, the emperor included the title “the Roman Hercules” as part of his nomenclature, while the demigod was also incorporated into the renamed months of the Roman calendar (along with Commodus’ name). This imperial megalomania circulated around the empire; it was not a phenomenon limited to the city of Rome. An altar recovered from Dura-Europos, on the southwestern bank of the Euphrates, is evidence for the spread of the idea of Commodus as Hercules to even the furthest limits of the empire. Images of Commodus in the guise of Hercules circulated the empire, ranging from coins through to artwork, including perhaps one of the most famous statues to have survived from antiquity.

Commodus’ association with Hercules also went hand-in-hand with gladiatorial combat. Dio reports that the emperor’s club and lion-skin — immediately recognizable icons of Hercules’ identity — were carried before the emperor in processions, and they were also placed in Commodus’ gilded seat in the amphitheatre. Commodus would appear in the arena and mimic Hercules’ feats. Displays of his prowess with a bow were meant to serve as an imitation of Hercules’ sixth labour, the Stymphalian Birds.

Making Sense of Madness: Commodus, Hercules, and a New Empire

Fundamentally, Commodus’ masquerades as both gladiator and as Hercules can be understood as aspects of the same objective. These new paradigms of imperial power allowed the most nobly born of all Rome’s emperors to articulate a new version of status. Whereas the narrative sources for Commodus’ reign are quick to highlight that the emperor’s status derived from the dynasty — this was the most nobly born of all emperors, according to Herodian — the gladiatorial masquerade and the delusions of Herculean grandeur offered Commodus scope for emphasizing his individual status, distinct from the achievements and reputations of his father and ancestors.

In the end, the experiment was a failure. Commodus was murdered on New Year’s Eve 192. His memory was condemned and his death was celebrated in Rome, not least by the senatorial elite who had conspired against him. However, the reign of Commodus had altered the dynamics of the Roman political landscape. In the decades that followed, new modes of representing imperial status and power emerged. Not all were so recognizable as Commodus’ approach, with Elagabalus’ championing of a Syrian sun god prompting a particularly violent reaction.

In the future, emperors would again turn to Hercules for a divine association, most notably under the Tetrarchs of the early fourth century. These emperors would be more successful in cultivating these links, but viewing the decades that followed Commodus’ reign — a time of crises in the Roman Empire — it is clear that the emperor’s Herculean delusions were also influential innovations.