Encaustic painting was a technique of painting with colored molten wax that originated in Ancient Greece. Over the following centuries, it traveled to Rome and Egypt and was later adopted by early Christian icon painters. In the modern and contemporary era, some artists revived the ancient technique, willing to experiment with mediums and materials. Read on to learn more about encaustic painting, its application, and conservation nuances.

Definition and Antique Origins of Encaustic Painting

Encaustic painting is an ancient technique of mixing hot molten beeswax with pigment and using it for painting. Encaustic paint creates a semi-transparent finish that dries almost instantly, forcing the artist to work quickly. The wax-based paint can be applied with brushes, cloths, and knives or simply be poured over the base material. Encaustic paint leaves thick textured brush strokes that sometimes can be sculpted or carved after the wax hardens. To fix the image, artists usually heat the entire surface of a finished work to bind layers of wax together and give a uniform glossy finish to it.

One of the prerequisites of encaustic painting is stiff back support for the painting. Wax is a soft and fragile material that would inevitably crack and break on a flexible background like canvas or paper. The artists of Greek and Roman antiquity mostly used wooden panes for their encaustic paintings.

Encaustic painting originated in Ancient Greece. The earliest written mention can be found in Pliny the Elder’s encyclopedia The Natural History. Over the following centuries, it was adopted by Christian icon painters but was gradually pushed out by mediums like tempera and oil. Apart from wax and pigment, ancient painters mixed in tar and oil. The proportions varied according to the work’s purpose: due to the physical properties of beeswax, encaustic paint for outdoor and indoor painting had to have different consistencies.

Fayum Portraits

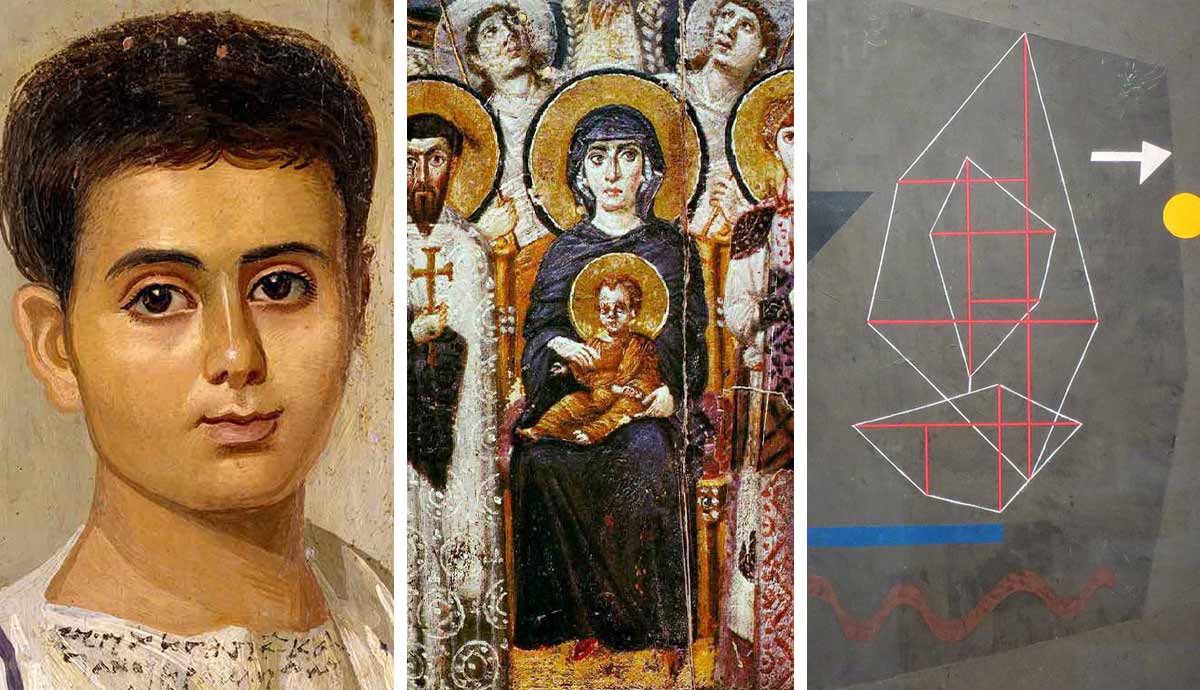

The so-called Fayum portraits are among the most famous encaustic paintings. Many were found at the Roman-Egyptian burial site in Fayum Oasis, which is how they got their name. These portraits, used instead of traditional masks, were placed directly over the body or on the sarcophagus. Fayum was an area populated with diverse ethnic groups, including Egyptians, Greeks, and Syrians. Local culture absorbed various influences and customs, resulting in an outstanding style of encaustic painting, incredibly detailed and realistic.

Today, archeologists have found about 900 Fayum portraits. Fayum Oasis was a burial site for elites, so the portraits show the luxuries and fashions of the time. Hairstyles, for example, are especially useful to archeologists. Although most portraits are from the 1st to 3rd centuries CE, experts can identify specific decades based on hairstyle length, styles, and other details. Many portraits were decorated with thin gold leaf that either covered the entire background of an image or highlighted details like jewelry and garment ornaments.

Apart from paintings, archeologists found papyrus with Greek and Egyptian texts, ceramic vessels, and objects for personal use. Starting from the 3rd century CE, encaustic paint was almost completely replaced by tempera. Tempera portraits, although as detailed as the encaustic ones, did not have the same glossy finish and nuanced contrast created with molten wax.

Christ Pantocrator

Another iconic work of art painted with encaustic technique was Christ Pantocrator, an icon from Saint Catherine’s Monastery near Mount Sinai. Christ Pantocrator is one of the oldest surviving Christian icons, dating back to the 6th century CE. Historians believe it was one of the images that cemented the iconography of Jesus Christ’s appearance and facial features. These features would later spread over different Christian denominations and become an instantly recognizable image of the Savior.

One of the most important features of Christ Pantocrator was the asymmetry of Christ’s facial features. This was a deliberate artistic choice: the right part of his face, bright and soft, represents his heavenly half, and the left, with a dramatically arched eyebrow and dark eye, relates to his human part and the suffering he had to endure. Some art historians noted the similarity of Christ Pantocrator to pre-Christian depictions of Sun gods. Many also note that at the time of the work’s creation, canons of Christian art had not yet existed. Thus, over the years, this image itself became the source canon.

At the time of the work’s creation, Byzantine authorities were fighting against the use of images in churches and destroyed many important artworks, yet the Sinai Monastery managed to preserve their treasures. Saint Catherine’s Monastery was one of the rare places that maintained the tradition of encaustic painting even when it fell out of favor and was replaced by tempera. Christ Pantocrator was originally painted with encaustic paint and preserved surprisingly well for its age. However, in the 8th century CE, an unknown painter restored the icon with tempera paint, partially covering the original encaustic image. Only in 1962 did art conservators remove the tempera layer, returning the icon to its original state.

Modern & Contemporary Encaustic Painting

Although usually, while talking about encaustic painting, we name Greek, Roman, and Byzantine examples of art, painting with molten wax was familiar and popular in non-European cultures as well. In the 17th century, Indigenous Philippians created art using a now-lost technique kut-kut, that involved maintaining with wax and scraping off parts of the image. After tempera and oil paint took over the art market, encaustic painting became obscure and almost went extinct. However, the 20th-century experiments and reinventions brought this art technique back.

Mexican modernists like Diego Rivera revived the use of encaustic paint. He painted his first state-commissioned mural, Creation, with encaustic paint, combining pre-colonial Mexican, early Christian, and Egyptian artistic traditions. As a reference to Byzantine art, he covered parts of the mural with gold leaf. Creation was painted inside the National Preparatory School in Mexico City and presented a complex composition of allegorical figures, including Hope, Science, Charity, and Faith.

Paul Klee, the famous modernist and Bauhaus professor, famously experimented with many art mediums and techniques. Encaustic painting was one of them. Klee mixed wax with sand and poured it over glass or painted canvas, only to scrape away fragments and reveal a pattern underneath. Klee’s whole oeuvre was one extensive, joyful experiment that included play with materials and forms. In Bauhaus, he encouraged his students to experiment as well.

In the 1950s, encaustic painting became popular among Boston artists associated with the Expressionist movement, like Esther Geller and Karl Zerbe. Abstract Expressionist painter Fritz Faiss, a former student of Paul Klee, went even further than simply painting. Faiss developed his own recipes for encaustic wax and patented them. Today, encaustic painting is rare in contemporary art but still appears, often combined with other materials. Artists may use encaustic elements in mixed-media installations or complex projects.

Restoring Encaustic Paintings: Sometimes the Old Ways Are Better

Wax is extremely soft and sensitive to hot and cold temperatures, thus art conservators have to be cautious to avoid causing more danger to artwork during restoration. In the early 20th century, art experts used paraffin to fix the damaged fragments of Fayum portraits. However, paraffin is more brittle than natural beeswax, and does not solve the problem of further deterioration. Over the years, art experts experimented with waterglass, plexiglass, and celluloid, but none of these methods proved to be functional enough.

The main problem with using synthetic materials to restore encaustic paintings is the uncertainty about how beeswax and pigment will react to them over time. For that reason, by the 1950s, most art conservators resorted to the most obvious choice and focused on restoring Fayum portraits with beeswax solutions. Despite technological development, it still remains the most preferable method to restore encaustic paintings regardless of the date of their creation.