The archeology of Chichen Itza, one of the last Mayan city-states, is controversial and subject to ongoing debate due in part to the site’s similarities to non-Mayan sites. Like Teotihuacan to the north, research suggests Chichen Itza was a highly syncretic society, combining traditions of both Toltec and Maya, evidenced by the remains of the structures slowly being unearthed there today.

The History of Chichen Before Itza

As the Maya civilization entered the Classic Period, 250-900 CE, it experienced a decline known as the Great Collapse, possibly related to its style of government, which relied on tribute to support cities’ growing populations. Most, if not all, Mayan cities utilized this style of government, so when one or another party failed to hold up their end of the bargain, either because of revolt, drought, or internecine warfare—just a few of the proposed causes of urban decline—the entire system fell apart, leaving only a few city-states, among them Chichen Itza and the later Mayapan.

The initial construction of Chichen can be traced to this Classic period, approximately 500-800 CE. These first settlements were in the Puuc architectural tradition following the decline of Teotihuacan, which was home to many groups, including the Maya, during its peak from 200-600 CE. Like Teotihuacan, Chichen became a largely syncretic society, at least in terms of style, after its initial occupation.

Later occupations of the site began around 900-950 CE as refugees from the collapsing Mayan empire migrated to the Yucatan from Guatemala and southern Mexico. By this time, sufficient trade relations had created mixed Mayan-Mexica/Toltec groups, among these the Itza.

The name Chichen Itza translates to “at the mouth of the Itza’s well,” combining the words chi meaning “mouth” or “edge,” with chʼen, meaning “well.” The name Itza was derived from the words itz, meaning “sorcerer,” and ha, “water.”

Who Were the Itza?

With the entrance of this Toltec group, the timeline becomes jumbled.

Popular theory holds that the Toltecs entered the valley of Mexico in the early Post-Classic period, around 950 CE, and built their city of Tula Grande near the settlement of Tula Chico, which had existed since the fall of Teotihuacan around 600 CE. Prior to this, it is believed that the Toltecs descended from a nomadic tribe known as the Chichimeca from northern Mexico. The word Chichimeca is equivalent to the Latin “barbarian,” while Toltec can be translated as “master artisan” as well as “an inhabitant of Tula.”

The Toltec story of Chichen Itza begins with the exile of a king known as Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl from the Toltec capital of Tula Grande around 987 CE. Mayan sources also speak of this king’s arrival in the Yucatan in the same year. Among the Maya, he was known as Kukulkán, but he may be better recognized by another name: Quetzalcoatl, a deity who had been revered in Guatemala, Belize, and Mexico for hundreds of years.

Archeology cannot rely on oral histories alone, which is why the timeline of Chichen Itza is still highly debated. Recent discoveries of an older, smaller temple within the Temple of Kukulkan and the results of radiocarbon dating from pottery fragments found in the great plaza around the Temple indicate an older date for both the temple and other monuments at the site. These discoveries place Toltec elements at Chichen Itza earlier than their capital city, Tula Grande, suggesting that, rather than a Toltec invasion of Chichen, a trade system existed going back hundreds of years whereby pottery and architectural styles were used contemporaneously, just as they were in Teotihuacan.

Taking carbon dating at face value leads to the conclusion that the Toltec and Mayan elements, known in the archeological records as Old Chichen (the pure Mayan elements) and New Chichen (the Toltec), actually existed contemporaneously, possibly as far back as its original construction following the decline of Teotihuacan in 600–800 CE.

This leaves the question of the Itza themselves. Upon their arrival in the Yucatan, the group known as the Itza were referred to as “the people who speak our language brokenly” by the existing Yucatec Maya. Their strange language may be a clue to their origins, which, like many aspects of Mayan civilization, are still up for debate. The most popular theory is that they were migrants from the Lake Peten region in central Guatemala, while others have suggested that they were a Nahuatl-speaking group of Chontal Maya who came south from Mexico.

With this in mind, a clearer picture emerges of an Itza-Toltec group that migrated south from Mexico, finally ending up in the city of Chichen, where they encountered an incumbent Maya population inhabiting the site following the Puuc occupation, or perhaps the Puuc themselves, resulting in the integration of the two architectural styles.

Chichen Itza: Model or Reproduction?

Similarities between Chichen Itza and other sites, particularly Tula Grande, support the theory of syncretism rather than invasion. The list of similarities between Tula Grande and Chichen Itza is extensive, essentially making one a model of the other, and while Tula Grande is much smaller than Chichen Itza, the carbon-dating analysis suggests that Tula Grande is younger than its sister Chichen Itza—and both bear resemblances to the much earlier Teotihuacan.

Perhaps the most striking similarities are found at the Platform of the Eagles and Jaguars at Chichen Itza, which bears a close resemblance to the Pyramid of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli (aka Quetzalcoatl) at Tula Grande. Both are three-tiered platforms surrounded by carved jaguar and eagle motifs, symbolizing the Toltec military orders of the eagle and jaguar, supporting the hypothesis of a syncretic government in Chichen Itza, just as in Teotihuacan.

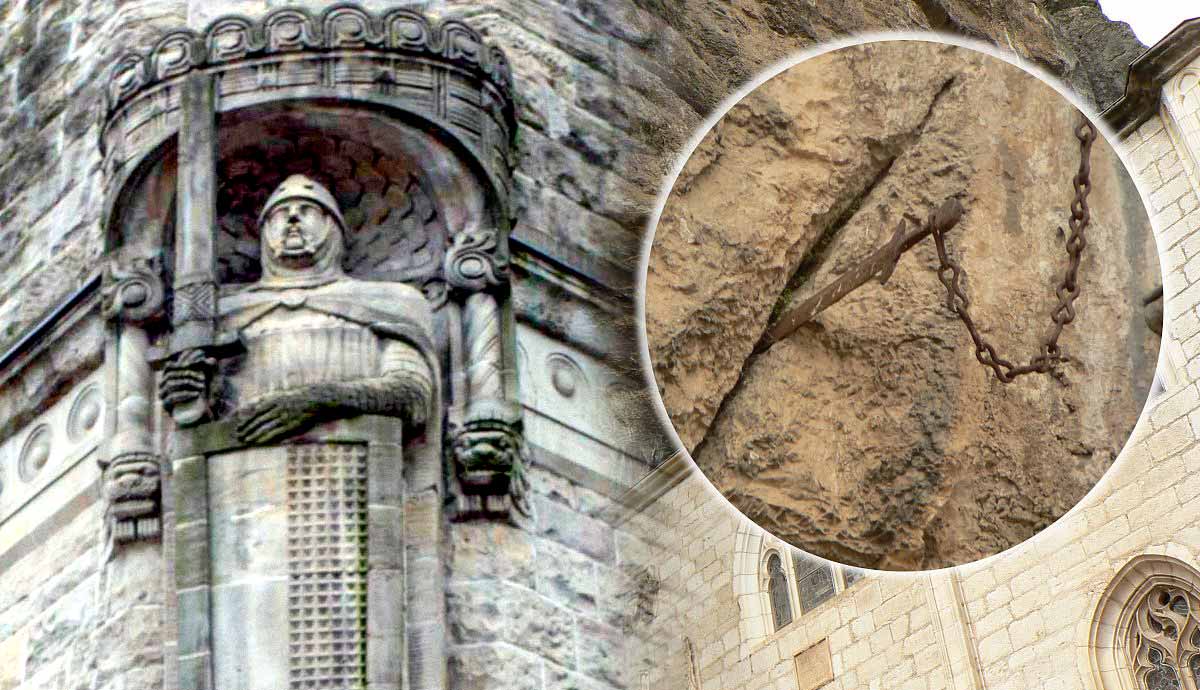

The Temple of the Warriors also closely resembles the Pyramid of Tlahuizcalpantecuhtli at Tula Grande, with three platforms surrounded by long colonnaded halls. At the top of the stairs stand rows of stone pillars decorated with eagles and jaguars devouring human hearts. The version of the temple at Tula Grande (also known as “House of the Morning Star” or “The Temple of the Lord in the Dawn”) is topped by eight stone pillars, four in front and four in back, each standing 15 feet tall. The four in the front are called the “Atlanteans,” wearing the Toltec pillbox helmets and carrying the atlatl spear-throwers as part of their regalia. These figures would have represented the elite Eagle and Jaguar warrior classes. Their arrangement in sets of four also suggests an association with the four brothers of the Aztec pantheon, the four Tezcatlipoca: Huitzilopochtli, Xipe-Totec, Quetzalcoatl, and Tezcatlipoca himself.

During the Itza-Toltec period, the chacmool altar also began to appear, present in the later Aztec Tenochtitlan as well. The chacmool is a stone statue in the form of a reclined figure wearing the Toltec helmet, holding its hands on top of its chest, forming a kind of bench or chaise lounge. Generally assumed to be part of the Mayan ballgame, these chacmool altars occupy public as well as private spaces, suggesting different uses for the same object, but all are believed to have sacrificial purposes.

Whether the players themselves were sacrificed is debatable, as the ballgame was played extensively throughout Mesoamerica. Assuming that sacrifices were involved, the altar may have been used to hold the heart of the sacrificed party (either the winner or the loser), while in other cases, the altars would have held food items, such as maize or vegetables.

Highlights of Chichen Itza’s Architecture

Excavations in 2009 revealed evidence of an immense earth-moving project that flattened the central plaza around the Temple of Kukulkan and the ballcourt. This leveling of the site is now recognized as the largest of all structures in the Chichen Itza complex, known as the Grand Terrace. Several floors have been discovered below the present-day level of the plaza. With each new floor and each new addition to the complex, the Grand Terrace was extended, eventually reaching the road leading to the Sacred Cenote, some 1000 feet north of the main plaza or Grand Terrace.

Among all the structures, El Castillo is the most recognizable, the first thing visitors see upon arriving from the main access road. The structure is known for its peculiar “snake shadow,” cast during the spring and autumn equinoxes by the nine graduated platforms as they play upon the intervening stone balustrades on each of the pyramid’s four sides. Each side also has a stairway with 91 steps, adding up to a total of 364, with the final platform equal to 365.

The site of the temple itself was chosen as the “center of the world,” with each face roughly oriented to one of the cardinal directions and built atop a cenote, or sinkhole, to facilitate ceremonial practices, as the name Itza, “water sorcerers,” suggests.

Adjacent to the Temple of Kukulkan is the Great Ballcourt, the largest of its kind in Mesoamerica and one of 13 others in Chichen Itza itself. The court measures approximately 230 feet wide by 545 feet long and is 26 feet high. While average compared to a soccer field, considering the hoops for the ball to go through are about 35 inches in diameter and located 20 feet in the air, and the ball (measuring 6 inches in diameter) had to be bounced off of a stone yoke tied to the player’s hips, it is unlikely that anyone was able to score any points at all. What that meant for the winners and losers is unclear, but given these circumstances, it is more likely that the Great Ballcourt was reserved for other more ceremonial purposes, while the smaller courts, measuring a fifth or a sixth of the size of the Great Ballcourt, were much more conducive to playing.

As noted, the Itza were “water sorcerors,” so one of their most important sites was the Sacred Cenote, arguably the reason the site of Chichen Itza was chosen in the first place. Looking like a giant well, the Sacred Cenote is 200 feet in diameter and drops 89 feet to the surface from the ground above. There are no rivers in the Yucatan, so these cenotes provide a large portion of the water used by the residents, the other portion coming from rain. There is no shortage of cenotes in the Yucatan, by some estimates as many as 8,000 to 10,000 in the vicinity of the city alone. While it could have been used for drinking and bathing, the Sacred Cenote’s primary purpose was ritual. Excavations of the bottom of the cenote have yielded artifacts of jade, obsidian, wood, and small amounts of gold, along with human skeletons.

Chichen Itza’s Future as a World Wonder

It is important to consider that at the time of the “rediscovery” of these sites in the late 1800s, they had become part of the surrounding jungle; only the tops of many of the structures could be seen. Unlike Tenochtitlan to the north, Chichen Itza, at the time of European contact, was not the center of civilization it had been in the Classic Period. Although there was a thriving population in the vicinity of the city, it had already started to deteriorate. Much of what can be seen now in Chichen Itza and other Mayan cities are reconstructions; most of the larger cities are inaccessible to tourists and completely taken over by the surrounding forest. The only reason Chichen Itza is in as good a shape as it is is its popularity, which keeps the vegetation in the area under control.

The larger city, of which the great temples are only a part, covers an area of 10 square kilometers (6 miles), much of which may never be studied. In the main plaza alone, excavations have only scratched the surface—literally, uncovering floor after floor of past occupations. The volume of unknown information about the Maya and the Toltec-Maya far outstrips what is known.

What has resulted is a very New Wonder of the World indeed. But even with its extensive daily tourist population, the city still maintains its mysterious gravitas, an unearthly sense of occupation that exists now as much as it did then.