In the 1880s, the powers of Western Europe had not fought a war with each other for some 70 years. As each power grew stronger, they sought to create a hierarchy of geopolitical strength. With all land in Europe having long been claimed, these powers turned their eyes to the nearest “unclaimed” land: Africa. Between the 1880s and World War I, European powers laid claim to all land in Africa aside from the independent nations of Liberia and Ethiopia (Ethiopia was itself seized in the 1930s by fascist Italy). Read on for a look at which European powers claimed which colonies in Africa, and why.

Setting the Stage: Power Struggle in Europe

Seventy years after the final defeat of French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo, western Europe had been relatively peaceful. Over the past three decades, nation-states had merged to create the new nations of Germany and Italy. In southeastern Europe, the Balkan territories were breaking away from the Ottoman Empire, and each wanted the backing of a larger, western European power. This created an international competition among the western European powers to show off their military strength and geopolitical influence.

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 largely kept Europe from re-colonizing the Western Hemisphere after the independence movements in New Spain, and the loss of cotton exports from the southern United States during the American Civil War (1861-65) led Britain and France to look closer to home for natural resources they could import. Thus, by the 1870s, Europe was looking to the Middle East and Africa. The completion of the Suez Canal in 1869 also made it easier for European powers to access the east coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean. Competition for colonies now intensified further, as both coasts of Africa (and South Asia) were easily accessible by ship.

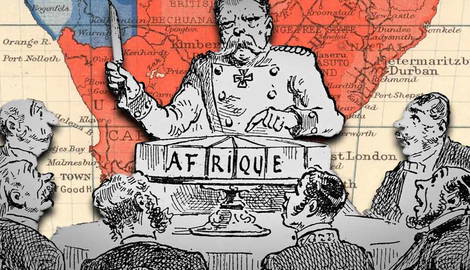

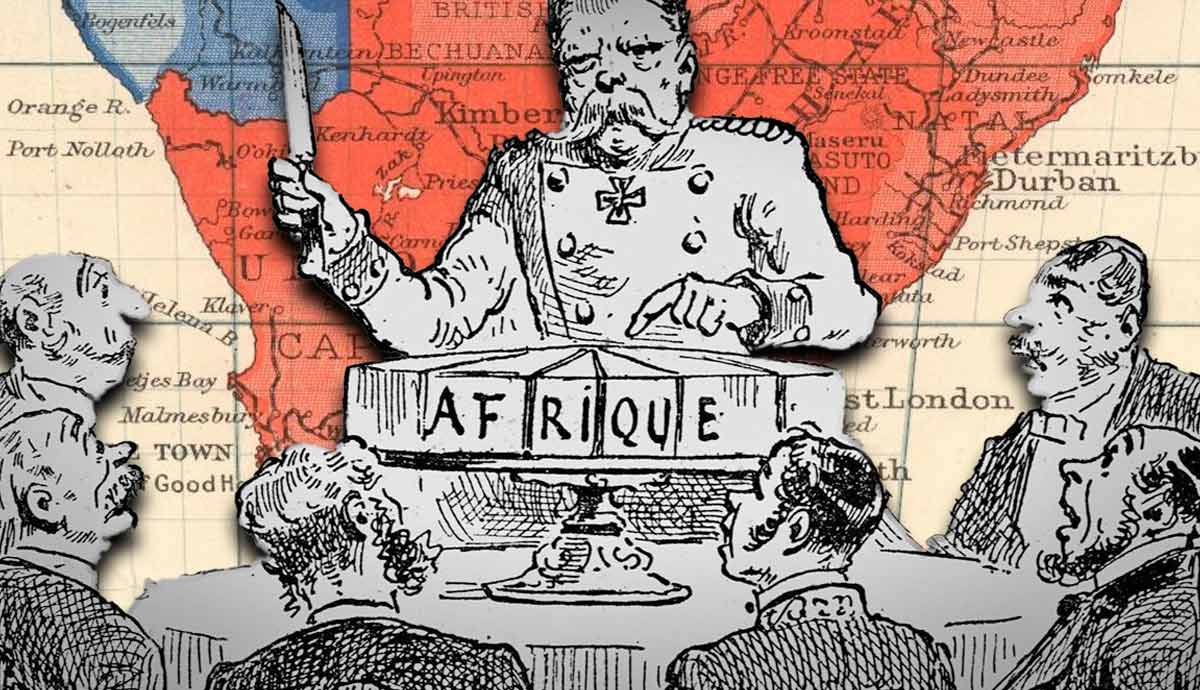

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85

Now able to more easily access Africa by ship, European powers sought to colonize this continent for its bountiful natural resources and cheap—or de facto slave—labor. Hoping to avoid potential wars, German chancellor Otto von Bismarck (the head of the unified Germany) called a conference of European powers in Berlin in 1884. The task would be to divide up the continent of Africa in a “civilized” manner. Fourteen European nations attended, as did the United States. Of course, no representatives from Africa were invited.

Many parts of Africa had already been explored and relatively colonized by various European powers. The Berlin Conference was intended to formalize zones of colonization to prevent future conflicts, as well as discuss trade among the colonizing powers. On February 26, 1885, the conference was concluded, with seven European powers having been granted zones of colonization. Frequently, these borders were drawn without any regard for native people or habitats. Many of today’s national borders in Africa come from lines arbitrarily drawn at this conference.

1. French West Africa

The French had already been active in West Africa prior to the Berlin Conference, with a port in modern-day Senegal as early as 1659. By the early 1800s, French explorers were moving into the interior of Africa. In the mid-1800s, the French conducted most exploration, and de facto colonization, through the use of military expeditions. The Berlin Conference gave France the majority of West Africa, which it united under the banner of Federation of West Africa in 1895. Even today, French remains the most common unifying language in most West African nations.

While the French were less directly oppressive toward native people than the British, especially given the history of the transatlantic slave trade, they sought to “civilize” Africa in their own image and prevent the spread of Islam into French West Africa. In 1911, France banned the use of Arabic in government affairs, ensuring that French was the uniform language. Although this caused some outrage, France was able to maintain some local acceptance of colonial rule by allowing Africans to become “Europeanized” and reach positions of power and authority.

2.1 British Egypt (North Africa)

Britain and France had fought over control of Egypt for years. Although Napoleon had invaded in 1798, he had been defeated the following year by the British and the Turks. The British returned in the mid-1800s, as they were now building trade routes through the region to reach their “crown jewel” colony of India. In 1882, Britain de facto took over Egypt as owner of the Suez Canal. When faced with internal resistance to this takeover, Britain responded with an invasion of some 35,000 British and Indian troops.

Toward the end of that same year, the British began to look to the south of Egypt, at Sudan. An Islamic uprising there was considered a threat to British rule in Egypt, so Britain expanded its empire. In 1884, after Egyptian forces had been defeated, Britain itself sent troops into Sudan. Although British troops won some skirmishes, they were unable to quell unrest, and eventually left Sudan. Twelve years later, concerned that other European powers might conquer the area instead, the British returned in force. By the end of 1898, both Egypt and Sudan were firmly under British control.

2.2 British South Africa

As the world’s most dominant colonizing power, Britain had a separate zone of influence in South Africa at the same time as its expeditions in Egypt and Sudan. Britain had established a colony at the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of South Africa, in 1815 to block the French from accessing the region. However, British colonists often clashed with the Boers, who were descendents of the original Dutch settlers from the 1600s. For decades, the British and Boers clashed over governing issues, especially slavery; the Boers used slave labor in the early 1800s, while Britain had abolished the practice in 1834.

Beginning in the 1880s, influenced by the discovery of gold in South Africa, Britain began attempting to annex Boer territory further inland, sparking two Boer Wars. The second, fought from 1899 to 1902, was a more formal, industrialized war and is typically the one referred to when referencing “Boer War.” The Boers stunned the British by going on the offensive and winning the first skirmishes, which was a major upset for the vaunted British Empire. Despite superior Boer tactics and leadership, the British eventually turned the tide through sheer manpower—up to 400,000 troops from various parts of the Empire. Painful lessons learned during the war helped modernize British military training, giving the nation an advantage a dozen years later when World War I erupted in Europe.

3. Portuguese Angola (and Smaller Territories)

Spain and Portugal began European exploration of other continents during the 15th century, and the Portuguese landed in Angola as early as 1483. Unfortunately, Portugal came to use many of its colonial sites in Africa as slave trade centers. As some of the earliest European colonizers and excellent seafarers, the Portuguese stuck mostly to the coasts of Africa and traded for gold and ivory. Eventually, Portugal came to control two large colonies: Angola and Mozambique. By the early 1800s, Angola in southwest Africa was the largest source of enslaved Africans, with many bound for North America in the transatlantic slave trade.

The Berlin Conference split the large Kingdom of Kongo between Portugal, which annexed the western part into Angola, and Belgium, which created Belgian Congo. At first, the Portuguese stayed relatively close to the coast, only working inland by the early 1900s. Similarly, Portuguese control of Mozambique, on the eastern coast of Africa, began on the coast and slowly worked inland. Until 1822, Portugal also claimed the massive South American colony of Brazil, to which it exported many slaves from its African colonies. Having lost Brazil, Portugal worked hard to maintain its two remaining African colonies into the 1970s, only granting them full independence in 1975.

4. German South West Africa & East Africa

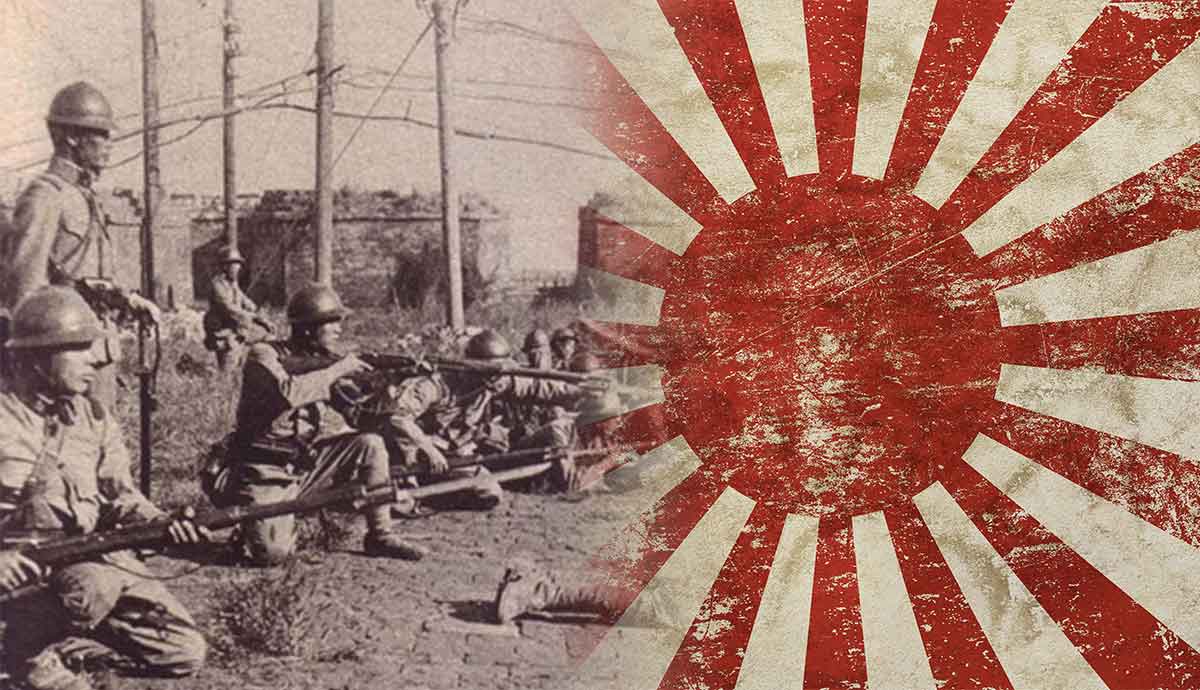

In 1886, Germany and Portugal agreed on borders between Angola and the German colony of South West Africa. Four years later, Germany built its first fort in the colony, which was known for its extremely dry deserts. Periodic revolts against German “protection” occurred during the 1890s and early 1900s. In 1907, the last resistance was defeated. When World War I began, British South Africa invaded German South West Africa. In July 1915, roughly one year into the war, the German colony surrendered and Britain took control. Thus, Germany had the shortest colonial reign in Africa of the several European powers.

During World War I, Germany was more successful in its East Africa colony, where it used guerrilla tactics to outmaneuver and surprise the British. Troops from Kenya, British South Africa, and Belgian Congo fought until the end of the war against small bands of German soldiers and their African allies. In November 1918, at the end of World War I, about 1,500 Germans under Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered to the British, making Lettow-Vorbeck one of the few military commanders who had never been defeated in battle.

5. Spanish Morocco

Across the Strait of Gibraltar, Europe and Africa are only separated by a narrow ribbon of water. Given their geographic closeness, it is little surprise that Spain had built a fort in Morocco as early as 1476. However, given Spain’s massive exploration in the New World (North and South America), Morocco was of relatively little interest until after New Spain had been lost to independence movements in the early 1800s. At the Berlin Conference, Spain formalized its control of Morocco to prevent its absorption by French West Africa. However, its actual control was limited to only a few cities, especially after the Spanish-American War was a disastrous defeat for the once dominant world power.

In 1909, having lost Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines to the United States a decade earlier, Spain began colonizing Morocco in earnest. During the 1920s and early 1930s, Morocco became an incubator of nationalism in the Spanish military, with more aggressive troops and officers stationed in the colony rather than in Spain itself. Many of these officers, including Francisco Franco, would play significant roles during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and lead to a Nationalist victory. In fact, the Spanish Civil War itself began with an officer rebellion in Morocco against Spain’s Republican government.

6. Italian Libya

Italy was one of most minor European players in the Berlin Conference’s Scramble for Africa. Like Germany, it had unified as a nation only recently. Unlike Germany, it was not a military power that could rival France or Britain. At the Conference, Italy was granted control of Ethiopia, in northeast Africa. Unfortunately for Italy, its attempts to lay claim to this territory met with resistance and early military defeats. Fierce resistance by Ethiopia’s king in 1887 led to the first defeat of a European army by an African army after the conclusion of the Berlin Conference.

Later attempts to gain control of Ethiopia through trade and communications led to the Italo-Abyssinian War (1889-1896), which resulted in Italy’s defeat at the hands of a surprisingly well-armed Ethiopian military. Italy returned to Africa fifteen years later by invading Libya, which borders the Mediterranean Sea, and wresting the capital city of Tripoli from Turkish forces. Although Italy was victorious in the brief Italo-Turkish War (1911-12), it struggled to pacify Libya. In 1934, under dictator Benito Mussolini, Italy invaded Ethiopia to avenge its earlier defeat, resulting in unsuccessful attempts by the League of Nations to end the hostilities. This Second Italo-Abyssinian War (1935-36) was a victory for Italy, but costly. British and Ethiopian troops would drive out the Italians early in World War II.

7. Belgian Congo

The geographically smallest European power in the conference, Belgium, had perhaps the most devastating colonial reign in Africa. The former Kingdom of Kongo in south-central Africa was claimed by King Leopold II of Belgium as his personal possession, to which he claimed to bring Christianity and civilization. Unfortunately, Leopold’s development projects in the Congo Free State used brutally forced labor. Leopold’s International African Society used torture to force locals to perform hard labor in making rubber and extracting ivory. Those who did not work hard enough could have limbs amputated or be hung.

In 1908, after facing increased international pressure, Leopold ceded his personal possession to the Belgian government, creating Belgian Congo. The terrible conditions in the Congo Free State inspired The Heart of Darkness (1902) by Joseph Conrad, a book about imperialism, racism, and hypocrisy. Belgium continued to control Congo until 1960, relinquishing it after unrest began in 1959 and continued to grow. In September 1959, a consortium of Congolese political parties demanded true independence and not more elections under the control of Belgium. In January 1960, the Belgian government finally agreed to immediate independence after facing a united front of all Congolese political parties.