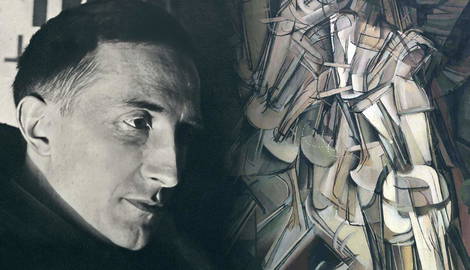

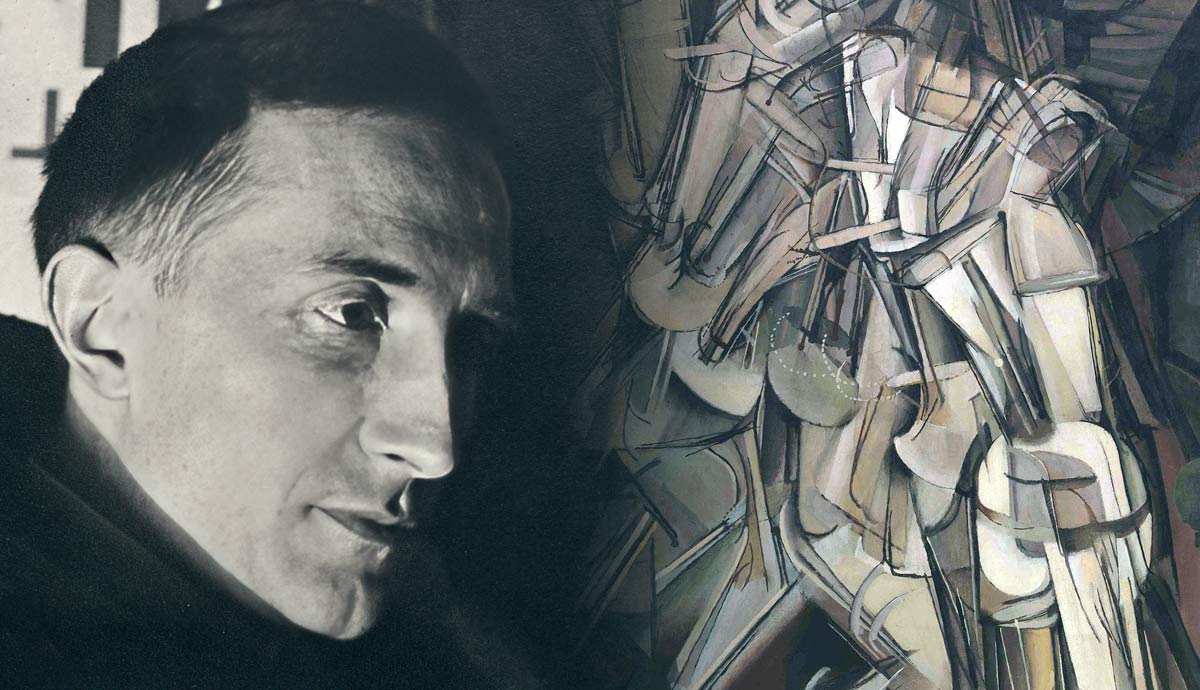

Marcel Duchamp is one of the most famous artists of the 20th century. However, fame never interested him. It took him 20 years to finish one of his most notable works, Étant donnés. Is it possible that his disinterest in fame or the fact that he created, first and foremost, simply to materialize his ideas, was exactly what led to his worldwide recognition? We will probably never know for sure. Nonetheless, let’s discover some other curious things about him!

1. Marcel Duchamp’s Siblings Were Also Artists

Marcel Duchamp was the son of Lucie Duchamp and Eugène Duchamp. He had seven siblings, one of whom died as an infant. Four of them, however, including Marcel, pursued a career in the arts. Duchamp’s siblings played an important role in his development and growth both on a personal and artistic level. They probably inherited their passion for the arts from their maternal grandfather who was a painter and an engraver.

The eldest brother and Marcel’s mentor was Gaston Duchamp, who eventually began using the artistic name Jacques Villon. He first studied law at the University of Paris but soon realized that he wanted to be an artist. Although he was part of several artistic groups, Jacques worked only on commercial art projects for a long time. He contributed to Parisian newspapers with illustrations and cartoons. Jacques’ art was influenced by Fauvism, Cubism, and Impressionism.

Raymond Duchamp-Villon also did not initially study art. Instead, he studied medicine at the Sorbonne. Unfortunately, he had to give up his studies due to rheumatic fever. Eventually, he turned to making sculptures.

Suzanne Duchamp-Crotti, the youngest sibling, played a significant role in the development of Dadaism in Paris. She was particularly renowned for exploring gender dynamics, having been a female figure in an art movement that included predominantly men. She was also greatly overshadowed by her brothers’ art. Nonetheless, she never gave up and her artistic career was five decades long. Suzanne left behind an extensive legacy that influenced other soon-to-be artists. In 1967, Marcel organized an exhibition dedicated to the art of the Duchamp family as the last surviving sibling.

2. Duchamp’s First Works Were Impressionist

Although Duchamp sought to distance himself completely from retinal art and even condemned it for its inability to stir one’s intellect, his first works were actually Impressionist paintings. He painted the landscapes in Blainville using techniques employed by Claude Monet. However, his Impressionist tendencies didn’t last too long. Duchamp abandoned oil painting altogether for some time after making the Blainville paintings.

A few years later, he turned to a Renaissance technique. This implied using black and white oil paint as a base, which was subsequently covered in layers of transparent colors—a technique known as glazing. Although this, too, was not to his liking, it marked a clear separation from the Impressionist concept.

3. The Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 Was Controversial

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was created in 1912 and, unexpectedly for Duchamp, steered much controversy in the art world. In Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Duchamp aimed to represent movement through a painting. In 1912, Duchamp submitted this work to an exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. It was accepted and eventually appeared in the catalog under number 1001. However, the painting was never displayed at the exhibition. Albert Gleizes, Jean Metzinger, and other members of the group were instantly taken aback by Duchamp’s piece. First, the title wasn’t Cubist enough. According to them, painting a nude descending a staircase did not do the nude justice.

The committee thought that the painting was rather Futurist and not Cubist. So they asked Marcel’s brothers, Raymond and Jacques, to talk his brother out of exhibiting the piece. Instead, Duchamp went straight to the exhibition and took his painting home.

It seems that this particular event and the controversy stirred by this painting prompted him to submit other artworks under pseudonyms. Some art historians believe that by submitting under pseudonyms, the artist tested the openness of a particular committee to the freedom of expression and the expansion (or questioning) of the definition of art.

4. Duchamp Preferred to Spend Time Alone

While many artists preferred being around other people and spending time in artistic circles, Duchamp had a slightly more evasive personality. At first, while living in Montmartre, he tried to lead a more social lifestyle. He was even evicted from his Montmartre apartment after hosting a Christmas party that went on for two days. After that, he moved to Neuilly, where he was more isolated, sometimes not leaving the house for days. However, he never refused the company of his siblings.

Furthermore, the months he spent in Munich in 1912 were, most likely, solitary as well, but little is known about his time there. It seems he didn’t encounter too many people who could account for their interactions.

Nonetheless, it seems that his personality changed after he moved to the United States, possibly because he felt more comfortable in New York than in Paris. He started going out more, meeting other artists, and making new friends.

5. Duchamp Worked as a Librarian

A year after the unpleasant event with Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, Marcel Duchamp took a job as a librarian at the Sainte-Geneviève Library. He needed to supplement the allowance from his father and at the same time, step away from art for a while. One of his friends’ uncle, Maurice Davanne, was the director of that library and he helped Duchamp enroll in a librarian course at L’Ecole Nationale des Chartes. This was a period of significant discoveries for Duchamp, which would later be observed in his work.

He studied math and physics, read a lot of books written by the French mathematician and theoretical physicist Henri Poincaré, and, lastly, started experimenting with combining art with science. He did not give up on art altogether, he simply changed the course of his artistic thinking. Duchamp himself stated, “There are two kinds of artists: the artist who deals with society; and the other artist, the completely freelance artist, who has nothing to do with it–no bonds.”

6. Duchamp Never Read Much

This may sound a bit contradictory to the last fact you read about Marcel Duchamp. Well, it is nonetheless true. While Marcel was indeed fascinated by scientific literature and took advantage of his time working at the library to read some famous works, he was never really an avid reader. The artist thought that words couldn’t express anything. On the other hand, he was quite impressed by poetry, particularly the titles of poems. He was also passionate about wordplay.

7. Duchamp Was in Love With His Lifelong Friend’s Wife

Marcel Duchamp met Francis Picabia in 1911, at the Autumn Salon. They quickly became good friends and started spending time together. Over the nights spent at the Picabias’ apartment, Duchamp seemed to have fallen in love with his friend’s wife Gabrielle who was an intelligent, beautiful woman. Eventually, he telephoned Gabrielle one evening, telling her he was in love with her. He also sent her several letters about this.

The two scheduled a rendezvous once, for which Duchamp took the train from Munich to Andelot in the Jura. They met at the train station and spent a few hours talking. Although their relationship remained platonic, art historians believe that Marcel’s love for Gabrielle had a major impact on his personal and artistic self. It is believed that Gabrielle and Marcel did have a relationship after she eventually left her husband.

8. Duchamp Emigrated to the USA

When World War I started, Duchamp was exempted from military service due to a heart murmur. After this, he decided it was the perfect time to move to New York City.

He did not identify with any European artistic tendencies, instead, he sought to create his own. He did not understand the present concerns of his fellow artists, so he felt a bit isolated in France. Although Duchamp knew he should leave for the USA, he was sad to leave his siblings behind. He arrived in New York in June 1914. To learn English, he decided to teach French classes to those who spoke a bit of French so that they could all exchange knowledge.

Duchamp was particularly fascinated with New York’s skyscrapers and the rapid development of the city. As such, he considered that Europeans valued the past too much by preserving old buildings. New York, on the other hand, did not allow the past to be stronger than the present.

9. Duchamp Didn’t Like One of His Masterpieces

After taking a long break from painting on canvas, Duchamp set on to make Tu m’ in 1918. This was a large painting encompassing the shadows of some of his readymades.

During that time, the artist spent all his spare time researching his future work, The Large Glass. He oriented his efforts toward moving further away from what he called retinal art. This was the reason why he did not particularly like Tu m’, while critics considered it one of his masterpieces. He felt like the piece didn’t advance his research at all.

Even the painting’s title suggests this. Tu m’, translates as you and me (as a direct object) and can be followed by any French verb beginning with a vowel. It has been suggested that the title was actually supposed to be Tu m’emmerdes or Tu m’ennuies, which would translate as you bore me, although this theory hasn’t been fully confirmed. After making this work, Duchamp never painted on canvas again.

10. Marcel Duchamp Was a Master of Wordplay

Throughout his life, Marcel Duchamp showcased his love of wordplay. Multiple painting titles contain puns, alliterations, and other types of wordplay that would be unnoticeable at first sight. Take, for instance, his painting entitled Jeune homme triste dans un train, which translates as Sad Young Man in a Train. It appears that Duchamp made the young man sad only because triste sounded well alongside train. Critics, on the other hand, rushed to comment on the psychological implications of the title. Was it indeed an indication of the author’s feelings, or was it just wordplay? We’ll probably never know for sure.

Duchamp also had an alter-ego called Rrose Sélavy. Her name is also another form of wordplay. At first, she was simply Rose Sélavy, which in French reads as Eros, c’est la vie (translating as Eros, such is life), where Rose was the most banal French name for a girl. Then, he added another R to the name, so his alter-ego became Rrose Sélavy.

The title of one of Duchamp’s most famous readymades Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette also came out of wordplay. The perfume was originally inscribed with Un air embaumé (perfumed air) and Eau de Violette (Violet Water). Duchamp, alongside Man Ray, an artist whom Duchamp worked with, simply swapped i with o and got Eau de Voilette, which translates as Veil Water. The other part, un air embaumé, became Belle Haleine, which translates as Beautiful Breath.