In the 4th and 5th centuries CE, the Roman Empire was flooded with Germanic warriors who split the Western Empire into a series of successor kingdoms. While this period is sometimes known as the Dark Ages, the pattern of cultural change was complex and region-specific. Most of those who took part in the so-called barbarian invasions admired the Roman Empire, and sought to emulate the Roman way of life. From the Vandal renaissance in North Africa, to the law codes of Visigoth Spain, many aspects of old Roman life were retained for some time in these new kingdoms.

Other regions changed more rapidly, losing their vibrant urban culture for many centuries and all the Western Kingdoms were negatively impacted by long-lasting political instability. After the fall of Rome, a few of these new states achieved great longevity, while others would have a very brief heyday, before collapsing into dust. Here is a brief introduction to the 5 major barbarian successor states.

1. The Vandal Kingdom In North Africa After the Fall of Rome

The Germanic Vandals who participated in the fall of Rome, settled in the Roman provinces in Africa, creating a short-lived but prosperous kingdom there. The Vandals had once been on positive terms with Rome, after a peace agreement made during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, and some of them had been granted lands in the Roman province of Pannonia, under Constantine I.

During the barbarian invasions of the 5th century however, the Vandals became Rome’s enemies, crossing the Rhine border in 406 to loot the empire, along with many other opportunistic tribes. Finding the provinces of Gaul and Hispania by now quite crowded with other roving warbands, the Vandals took the chance to cross from Spain to North Africa in 429.

When in Africa, they slowly spread across the continent, absorbing most of the Roman provinces there. While the Western Roman government tried to broker a deal to make them subjects of the Empire, the Vandals had soon established themselves as an independent power. The Vandals attempted to maintain a close relationship with late Roman Italy anyway, but they would end up sacking Rome itself in 455, when this arrangement was threatened by a change of emperors.

Italy relied heavily on grain from Africa to feed its citizens, and the late Roman government would attempt to reclaim the region but failed miserably. The Vandal’s long history of contact with the Romans would have a profound influence on their way of life, and despite their far-flung origins, the Vandals took to their new lifestyle on the African coast with gusto.

After capturing some of the most important seaports in the Mediterranean, including Carthage, the brand new Vandal navy became a force to be reckoned with, seemingly overnight. So much so that the Old English word for the Mediterranean is the Wendelsæ.

Life in Vandal Africa

The Vandals new maritime venture made them quite wealthy, providing them with the luxurious Roman lifestyle they so desired. While undoubtedly most of this wealth came from the raw materials and the trade in luxuries that Roman North Africa had once been famous for, the Vandals also gained a bit of a reputation for piracy.

Bolstered by their newfound wealth, the Vandal Africa emerged as one of the most successful, and one of the most Roman of the barbarian successor states. In stark contrast to the rest of the crumbling Roman Empire, the population of North Africa went up — not down.

In a time when towns were being abandoned in the west, archaeological studies of North Africa reveal that many Roman public buildings, such as baths, and palaces were expanded and repaired, and private dwellings such as Roman townhouses were built and rebuilt, in an effort to keep up the lavish Roman lifestyle.

Vandal North Africa was in fact so culturally Romanized that we know very little about the Vandals themselves. The new rulers kept most aspects of Roman provincial government, including the Roman taxation system, and they continued to employ local African staff.

Intellectual life also continued in Africa to some extent. The Vandal aristocracy sponsored Latin Poets just as the Romans had done, during a period that is sometimes known as the Vandal Renaissance. These Poets such as Luxorius, give us a glimpse of the highly Romanized culture of the Vandal kingdom in their verses.

In spite of their many successes, the Vandals gained a poor reputation, partly because they adopted heretical Arian Christianity, and persecuted Catholic Christians with great vigor. Using religion as a pretext for invasion, the Byzantines would soon descend on North Africa, reconquering the region in 534.

2. The Ostrogothic Kingdom

The Ostrogoths were one of the Germanic tribes who settled in the Balkans during the barbarian invasions of the 4th and 5th centuries CE. Before long they had united under King Theodoric, who took his armies to Italy in 490, conquering the vulnerable and by now war-torn peninsula. The last Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus had recently been deposed by another Romano-Barbarian General, King Odoacer.

After the fall of Rome, the exasperated Eastern Roman Emperor Zeno asked Theodoric to reconquer Italy, in a bid to get the Ostrogoths to leave his own lands, and to rid himself of the troublesome Italian King at the same time.

When Theodoric took the throne in 493, the machinery of Roman government continued to function much as it always had. The Ostrogoths kept the Senate as a feature of Italian government, and they focused on building great churches and other monumental structures across the kingdom.

King Theodoric was, in theory, supposed to be an agent of the Eastern Roman Emperor, and he styled himself as a Roman leader. We are told that Theodoric was named the “new Trajan” and the “new Valentinian” by his supporters, although in reality he had little in common with the emperors of old.

Theodoric’s relationship with the Roman aristocracy was ultimately uneasy. As tensions with the Eastern Romans began to escalate, a paranoid Theodoric purged some prominent Roman aristocrats for alleged treasonous actions.

Among those arrested was the once powerful senator and erudite philosopher, Boethius, who is sometimes referred to as the last Roman, because he wrote one of the last great pieces of Roman literature, the deeply moving Consolation of Philosophy, while he was awaiting execution.

Material Decline In Italy After The Barbarian Invasions

While Theodoric kept his kingdom politically stable for a time, Italy’s prosperity in this period took an enormous nose-dive. No longer collecting revenue and goods from the rest of the Empire, Italy now had to sustain itself alone, leaving everybody much poorer as a result. The loss of goods from Africa was a particularly harsh blow, and we know from our sources that Italy experienced food shortages. While the city of Rome had once supported a population of over one million people in the 2nd century CE, it now sustained something in the region of only 20-40,000.

In spite of this huge drop in population, Italy retained much of its urban culture after the fall of Rome, unlike other parts of the Western Empire where many people fled to the countryside. Archaeology from the Ostrogothic and later Lombard period show that large Roman town houses were still occupied — although they were increasingly broken up into multiple smaller dwellings, as the local population became more impoverished.

Ravenna in particular was the capital of Ostrogothic Italy, and it received a cosmetic makeover. Several beautiful Ostrogothic monuments, including the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, are still standing today. The Ostrogoth hold on Italy and its hinterland was ultimately very short-lived. Italian cities like Rome and Ravenna were still attractive prizes to many people, and before long the East Roman Byzantines had challenged Ostrogothic rule, plunging the peninsula into a disastrous state of perpetual warfare once again, in the 6th century.

3. Merovingian Francia

The Frankish Kingdom is one of the most successful Barbarian states on our list, and we know a lot about the Franks because they became a major power after the fall of Rome. In the 5th century, the Roman province of Gaul was initially fractured into multiple kingdoms, split between the Burgundians, the Franks, the Alemanni, and the Visigoths, among others. The Franks were one of the many Germanic tribes who fought to control Gaul, occupying the North, and eventually swallowing the rest of what is now France. They also ruled over the Benelux region, as well as large stretches of Germany, most of which fell outside of the Roman provinces.

While the Franks themselves were initially split into several groups, they were soon united under King Clovis I, who has historically been awarded the impressive title of first king of France. Clovis would begin the process of removing the Visigoths in the south, and he would inaugurate a stable and powerful kingdom, under the Frankish Merovingian dynasty.

Clovis also gave the Franks stability in another way, by immediately converting to Catholicism. He was the first barbarian king to do so; as most of the barbarian powers in this period were Christian Arians. Clovis’ pragmatic decision would prevent some of the problems that many other post-Roman states had —due to the religious conflict.

While Frankish Culture would soon grow to be quite prosperous, initially the region was devastated by an endless string of barbarian invasions. Nevertheless, elites in the early medieval Gaul, soon to be known as “Francia”, came out on top during this troubled period of European history, retaining for themselves a high level of wealth and power. Their successors, the Carolingian dynasty would later become the foremost power in Western Europe.

The Wealth Of Early Medieval Francia

Post-Roman Francia would retain a large and relatively abundant post-Roman economy. By the late Roman Period, Gaul had become a large center for industry, and Gallic products, such as Argonne-ware bowls, show up across Northern Europe. This important commercial center once supplied goods to the armies of the Rhine, and consequently Merovingian Francia inherited a large industrial heartland.

Francia continued to make products such as fine ceramics, metal tools, and glass, on a large scale, into the Early Middle Ages. Although the market for these products contracted substantially after the fall of Rome, Frankish wares still travelled a great distance along the Rhine, and Francia itself became a large and stable market. Other parts of the West suffered much more economically, due to greater internal instability, political fragmentation, and a loss of imports.

The Frankish aristocracy would also become quite wealthy, drawing their power not just from their military position, but also from large landed estates. Wills from the Merovingian era tell us that aristocrats accrued enormous tracts of land, making the dukes of the Merovingian court exceedingly rich, and Merovingian kings even more so. Nonetheless while this positive state of affairs benefited the Frankish elite, the medieval world that emerged in this period was much grimmer than the Roman world it replaced.

The Franks did not try to maintain the organs of Roman government the way the Vandals or the Goths did. While early medieval Francia would produce many wealthy individuals, the Merovingian government failed to maintain the Roman taxation system, and urban life rapidly declined in favor of a more agrarian society. The powerful moved to the countryside, and sophisticated Roman lifestyles were eroded in favor of a characteristically rural, and recognizably medieval state.

4. The Visigoth Kingdom

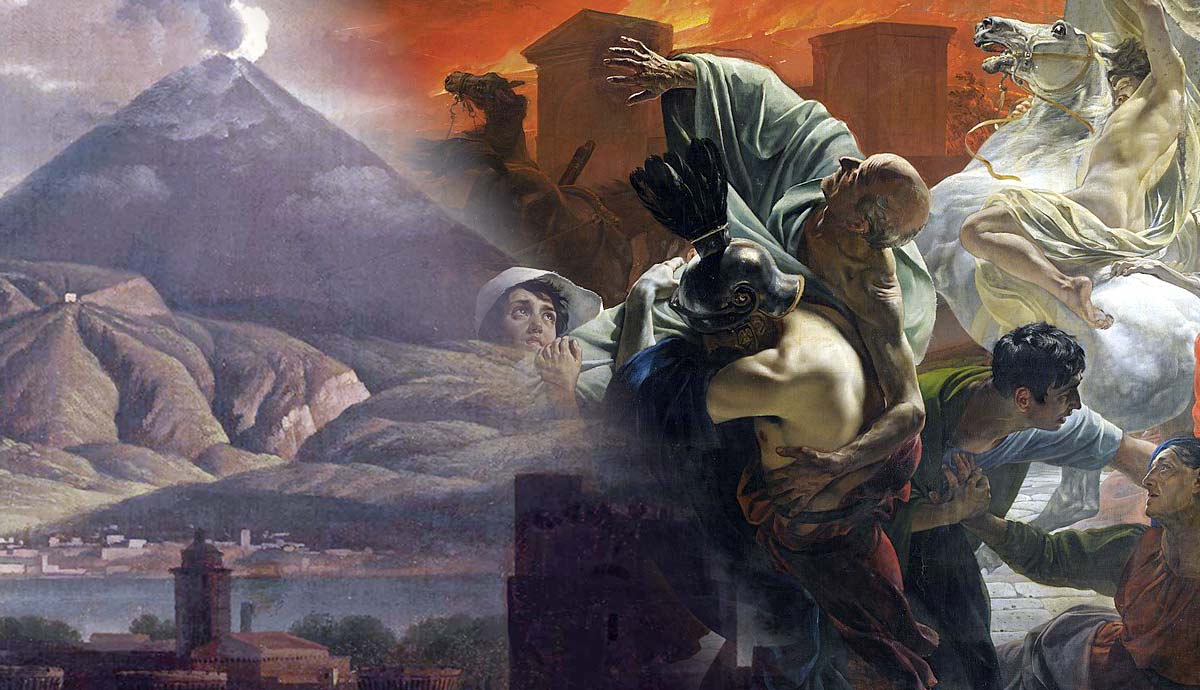

Of the tribes who contributed to the fall of Rome, the Visigoths have one of the worst reputations, for sacking the city of Rome itself in 410 CE. After they left Rome in disarray, the Visigoths would eventually form a kingdom of their own, conquering most of the Iberian peninsula, and the southwest corner of Gaul.

Their rule in Iberia would be challenged by several groups, including the Germanic Suevi, and the Basque-speaking Vascones, who later created the northern Christian Spanish kingdom of Navarre, and would prove a constant nuisance to the Visigoth Kings. After knocking heads with the powerful Franks, the Visigoths would also lose their lands in France altogether.

Nevertheless the Visigoths produced a fairly Romanized early medieval kingdom that lasted until the early 8th century. The Visigoths subscribed to the heretical Arian brand of Christianity which did not endear them to their subjects, and the Post-Roman Kingdom was generally fragmented and unstable for most of its history.

While the Visigoth kingdom may have lasted a lot longer under different circumstances, by the 7th century CE, the Prophet Muhammad had united the Arabian peninsula, and his successors, the Umayyad dynasty, would embark on a lightning fast campaign of conquest, absorbing lands all the way from the Middle East to Northern Spain. These extremely successful Muslim warriors would conquer the Iberian peninsula in just a few short years, between 711-718 CE, before they were finally halted in France at the Battle of Tours.

In the later Middles Ages, struggling Christian Spain would be inspired by the Visigoths, keeping alive the memory of a once united Christian Iberian Kingdom, as they fought for control of the peninsula against the Muslim Emirate of Cordoba.

Life In The Visigoth Kingdom: Rebellion And Integration

Like their counterparts in Italy, the Visigoths would attempt to rule as the Romans had done. The archaeology of Southern Spain in particular indicates that although the economy contracted, urban life continued much as before, and the writings of Isidore of Seville show that, at least in some places, Roman intellectual culture survived as well.

In addition to adopting the Latin language, the Visigoths were the great lawmakers of the post-Roman states. They continued to follow the Roman Theodosian Code before publishing their own law codes, aided by Roman lawyers.

While the Visigoths were keen to accept Roman ways of living, their attempts at integration were not enough to achieve peace in the Iberian peninsula. Visigoth legal documents reveal a large amount of instability in the region, as well as a troubling ethnic division between Goths and Romans. The divisions between ruler and subject was also dangerously reinforced by religion, until the Visigoth King Recared finally converted to Catholicism in 587.

The Visigoths subsequently seem to have struggled with an endless series of coups, and unlike the far more successful Franks, they failed to establish a hereditary monarchy. The Byzantine Emperor, Justinian I, took advantage of this chaotic state of affairs, and was able to gain a foothold in Southern Spain, adding to the Visigoths many problems.

Later Visigothic Kings would have more luck. King Leovigild in particular would carry out a series of military expeditions that helped to unite the peninsula, and he would attempt to emulate the Byzantine style of kingship. He would also remove any remaining legal distinctions between Goths and Romans, in a bid for unity. While the Goths and Romans merged over the next century, by the early 700s Iberia was still politically unstable, and the Visigoths were easily swept away by the Muslim conquests.

5. Early Anglo-Saxon England

Anglo-Saxon England developed in a completely idiosyncratic way, very different from the other post-Roman successor states. When Roman soldiers were removed from Britain in 410, the provincial administration promptly collapsed, and England went through a lengthy dark age.

Roman life in Britain was almost completely destroyed, and the Anglo-Saxon settlers would go on to have a very long afterlife, controlling England until the Norman invasion of 1066, and shaping English culture to a large degree.

The Angles, Jutes, and Saxons who arrived on British shores in the early 5th century are tribes we know virtually nothing about prior to the barbarian invasions. These tribes came from further afield than the other groups who took part in the fall of Rome, probably sailing from Denmark, Saxony, and Frisia, and they had neither adopted the Latin language, nor taken up Roman customs. These raiders had attacked the British coast before, and at least some of them were now hired by the vulnerable natives to serve as protection in the Roman army’s absence.

We know that one Romano-British leader with aristocratic roots, Ambrosius Aurelianus, had some small successes against the invaders, and he may have been the inspiration for the legends of King Arthur. In general, however, we know little about the events that formed Early Anglo-Saxon England.

The fringes of the UK, Cornwall to Somerset in the southwest, and Wales, remained unconquered for centuries, and they became the strongholds of the Christian Celtic Britons. These small British Kingdoms were probably never very Romanized to begin with, and they mostly retained their Celtic identity, speaking a language called Brythonic, instead of Latin. The fall of Rome would prove to be particularly difficult for Britain, and it would not easily recover from the barbarian invasions, becoming the least Romanized of the post-Roman states.

After The Fall Of Rome — Cultural Upheaval In Post-Roman Britain

While the archaeology of early Anglo-Saxon culture shows a drop-off in living standards and foreign imports, this trend actually began long before the fall of Rome, as political turmoil on the continent increasingly impacted British prosperity.

The gradual collapse of the Roman international trade network was devastating for an increasingly isolated island nation. After the fall of Rome, the fractured and anarchic situation that immediately replaced the Roman government and taxation system in Britain, shattered the economy still further.

Unlike the rest of the post-Roman states, Anglo-Saxon England failed to become a centralized kingdom, fracturing into many tiny states instead, ruled by petty kings. Urban life in Britain rapidly dissolved, as many major urban centers were entirely abandoned. In the West, where the native Britons kept control, old Iron Age hill forts were re-occupied by those looking for safety.

Culture also changed rapidly at this time. The Anglo-Saxons were the only invading nation to convert the natives from Christianity back to Paganism, forcing Rome to send a series of missionaries to Britain in the 7th century. England experienced a true dark age in the sense that we have almost no written sources from Britain for several centuries, apart from a few inscriptions. Most useful information about Anglo-Saxon England from this time comes from a British monk, named Gildas, who settled in Brittany in France, along with many other British refugees.

Later, when English culture began to blossom, Old English emerged as a distinctly Germanic language, initially written in runic script, in stark contrast to the Latin-based continental Romance languages. Britain would gradually begin to recover economically during the 7th century, and we have major sources for England by the 8th. Later Anglo-Saxon culture would grow to be rich, interesting —and it would retain much of its tribal Germanic character.