Forgotten at large in the 21st century, Ellen Thesleff had a career that spans the last decades of the 19th, all the way up to the middle of the 20th century. From her birthplace, the city of Helsinki, to Paris and Florence, Ellen Thesleff interacted with many contemporary movements, creating unique art pieces. The great movements of the late 19th and early 20th century, Symbolism and Expressionism, define her work. Relieving herself from the dogma of academic art, she freely experiments with various forms and techniques. Considering her use of color, Ellen Thesleff’s art ranges from almost fully monochrome to her late career’s vivid and bright works.

1. The Beginning of Ellen Thesleff’s Art: Echo

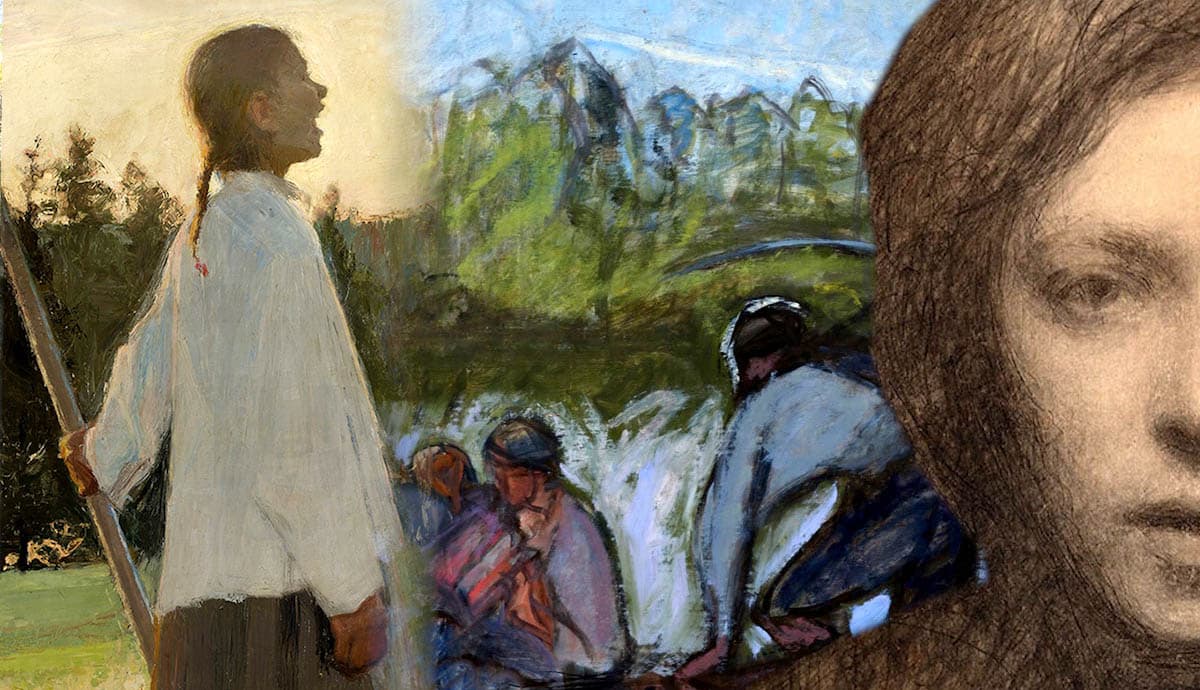

Ellen Thesleff made her debut and met with critical acclaim with the painting Echo in 1891. Ellen painted it during the summer, and it was accepted for the Finnish Artists’ Association’s exhibition. The show was highly successful and was her breakthrough as an artist, and it brought her the acknowledgment that both she and her family needed. It shows a young woman calling out, either in the morning or evening. Purposefully keeping the tones of the shirt simple, Thesleff chooses to emphasize and turn our eyes towards the head, surrounded by soft, warm light. The background also remains unknown, with simple trees, reinforcing the importance of the “call” itself.

2. Shifting Inward: Thyra Elisabeth

After moving to Paris in 1891, Ellen Thesleff’s art came into contact with a prevailing movement of the French capital, Symbolism. Thyra Elisabeth is a typical Symbolist painting based on a photograph of Ellen’s younger sister taken in 1892. A popular subject in Symbolist paintings, the female figure has typically been interpreted through archetypes such as angel, the Madonna, and femme fatale.

In the portrait of her sister, Thesleff creates a dialogue between the sacred and the profane, innocence and sensuality. Unlike the eroticized interpretations of the female physique, Thyra’s pleasure is indirectly implied through her facial expression, hair, and left hand holding a white flower – an ironic token of innocence. The background has been painted with a golden yellow tone that forms a barely perceptible halo around her head.

This dreamy appearance of the woman brings to mind Closed Eyes of Odilon Redon. In Symbolist art, the motif of closed eyes indicates a concern for a realm that cannot be perceived with physical vision. Painted and exhibited at Finnish Autumn Salon in 1892, this painting signaled a shift toward the portrayal of internal reality in her work.

3. A Vision of the Inside: Self Portrait

Ellen Thesleff’s art and philosophy cannot be fully realized without mentioning her Self Portrait, an artwork that was highly praised already in the 1890s and has come to be viewed as a masterpiece of Finnish art. Made with pencil and sepia ink, Thesleff’s Self Portrait epitomizes the attitude of inwardness and the desire to plunge into the very core of one’s own being.

This small-scale work of art, with an intimate quality, presents a pale face emerging from the darkness of the background. The eyes are open and directed at the viewer, but it is impossible to meet their gaze. Thesleff’s self-image represents the subject in full-frontal view, often considered the most communicative mode of representation. This way, the subject engages the viewer in an exchange.

Unlike usual frontal portraits, Thesleff’s self-portrait, rather than being a communicative image, appears to turn inward. However, it is not completely closed. It has a self-reflective quality that refers to the creative process. It is a process of self-exploration. The artist has looked into the mirror to see herself, but instead of stopping at mere surface appearance, she has penetrated deep into the realm of subjectivity.

4. Life in the Countryside: Landscape

Ellen Thesleff’s art is filled with scenes of the countryside and peasant life in Finland. Summers spent in the village of Murole gave her a lot of opportunities of roaming through woodlands, fields, and meadows. She inherited the Impressionist urge to find inspiration by connecting with nature. Thesleff often took out her rowboat and headed for Kissasaari, a small island in the middle of the lake, where she used to work en plein air.

The intense treatment of light is far from the light of Northern Europe and more reminiscent of the Mediterranean sun. This Landscape is one of the works in Ellen Thesleff’s art that shows a movement toward a more expressionistic use of color. In Finland, she gained admiration for her courageous avant-garde style of paintings. Finnish art critics associated them with a continental influence. In France, her art was compared to Matisse and Gaugin, while the Germans noted a similarity with Kandinsky and the circle of artists around him.

5. Florence, A New Model, and Poetry

Thesleff’s stays in Florence from the early 1900s coincided with a fresh stylistic turn away from Symbolism. Her painting shows the use of vibrant color, thick layers of paint, and forceful treatment of form. In Florence, Ellen experienced firsthand the art of Early Renaissance masters like Botticelli and Fra Angelico. The art of old masters inspired her to experiment with softer tones of pale pink and grey.

In the early 1910s, Thesleff found a new favorite model in Florence, a redhead named Natalina, who became the subject of her numerous sketches, woodcuts, and at least one painting. La Rossa is far from an ordinary portrait, though. Natalina enabled Thesleff to look into the mirror of her own artistic identity and creative philosophy. Writing to her sister Thyra, Ellen describes her new model:

“Auburn-haired Natalina is seated in a pool of sunshine – she has the neck of a swan and downcast eyes – I am painting on cardboard and I am immeasurably intrigued by her, but she is only free on Sundays.”

(December 16, 1912)

6. Motion & Vitalism in Ellen Thesleff’s Art: Forte dei Marmi

Another important aspect of Ellen Thesleff’s art is vitalism and motion. During her stays in Italy, she often visited the spa town of Forte dei Marmi, near Florence. Paintings from this small town portray people at play. In them, Ellen studies figures in motion, carefully observing how they interact with their surroundings. She focused on the bodily contrast.

Whenever the body moves in one way quickly, it is followed by a sequence of counter-movements to regain balance. These counter-movements are related to contrapposto, the classic pose of ancient Greek sculptures and found again in Renaissance art. Thesleff applies the same principle to convey dynamic tension when a figure gathers momentum to walk or run. This harmonious rhythm of the human figure is the crucial element in the painting Ball Game (Forte dei Marmi), made in 1909, as well as other paintings created in this spa town.

7. Gordon Craig & Woodcuts: Trombone Angel

Friendship with the English modernist and theatrical reformer Gordon Craig had a considerable impact on Ellen Thesleff’s art. Craig inspired her to make small black-and-white woodcuts and to develop later a colorful, painterly woodcut technique that became one of the key expressive forms of her career. Some of her woodcuts are unusually painterly, and her woodcuts and xylographs can be seen as variations on a theme, all colored in different ways.

The significance of woodcuts to Thesleff translates into paintings like Helsinki Harbour. The thin vertical broken brushstrokes look as if they had been carved into a block of wood, filled with ink, and printed like graphic art. In 1926, Ellen made this unusual art piece representing presumably an angel described in the Book of Revelations. This woodcut is based on a free sketch on birch veneer that was later cut with a knife. Colorful woodcuts like these made Thesleff stand out among Finnish artists, who mainly were making monochrome prints.

8. Music in Ellen Thesleff’s Art: Chopin’s Waltz

Music played a huge part in Thesleff’s life. All the children in the Thesleff household played musical instruments. Ellen played the guitar and enjoyed singing, favoring the music of Beethoven, Wagner, Chopin, Mozart, Mendelssohn, Schubert, and Finnish folk songs. Naturally, the love of music found its way into Ellen Thesleff’s art. Thesleff produced her first versions of Chopin’s Waltz as woodcuts in the 1930s.

Gracefully moving to the rhythm of Chopin’s music, the weightless appearance of the slender girl was influenced by the modern dance style pioneered by Isadora Duncan. Thesleff was familiar with Duncan’s work and had seen her perform multiple times in Munich and Paris. Isadora Duncan’s influence on Ellen Thesleff’s art possibly came also from Gordon Craig, the dancer’s former partner. In Symbolist art, whose influence reveals itself in some of Ellen’s later works, dance represents a particular form of expression in which the dancer is induced with a sense of transcendence.

9. The Ferry Man: Harvesters in a Boat

Throughout Ellen Thesleff’s art, we can find the ferryman as a recurring theme. The figure typically appears in the scenes that portray farmers returning home by boat. This theme is usually associated with death and loss. In the culture of ancient Greece and later European art, the boatman personifies death. In Greek mythology, Charon is the ferryman who carries the souls of the recently deceased across the river into the afterlife. Finnish mythology is familiar with the River of Death motif, in which a ferryman similarly carries souls to the world of the dead. In Harvesters in a Boat II from 1924, we see a typical scene from the life of Finnish harvesters, infused with an ancient theme that makes it universal.

10. Going Into Abstraction: Icarus

Though in her seventies, Ellen continued to be creatively active and held an important place in the Finnish artistic circles. In her later years, Ellen Thesleff’s art depicts a radical new non-representational style, almost purely abstract. Thesleff had been acquainted with abstract art from its beginnings. During the first decade of the 20th century, she came in contact with the works of Vasily Kandinsky. His works turned her attention to color painting. The expressive power of color was more than enough to carry the emotion and meaning of the work and project it onto the viewer.

Themes of ancient Greek mythology remained throughout her life as an opportunity to experiment with various techniques and forms. In the process, Thesleff created unique representations of ancient themes of European art. In this painting, an already familiar subject, Icarus, a youth who, in his arrogance, flew too close to the sun, comes second to her experimentation with color.