The famous Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni would denounce his colleagues’ assertion that one writes a film. He preferred to liken the process to painting. And that statement can be seen as true since cinema is, first and foremost, a visual medium. Just like a painter, the cinematographer must carefully curate all the elements of a scene to create a compelling whole. It is no surprise then, that it is possible to see the influence of famous artworks splattered across numerous films.

Famous Artworks and Mise-en-Scene

During the Renaissance period, artists like Leonardo Da Vinci and Raphael used the Golden Ratio and the rule of thirds to arrange elements within a frame. These aesthetic cheat codes found their cinematic counterparts in the use of the grid and framing techniques. Directors and cinematographers attempted to convey emotion and guide the viewer’s eye by drawing heavily on the rules of composition and framing that had already been established by classical painters in famous works of art.

There are many striking examples of scenes in films that have been directly inspired by famous paintings. This recreation of a still image is known as a tableau vivant or living picture. Take Gone With the Wind, Victor Fleming’s much-loved 1939 classic. In one iconic scene, Scarlett O’Hara vows she’ll never go hungry again before a scorching sunset. The composition of this shot was directly inspired by David Friedrich’s Woman Before the Setting Sun.

This painting is a typical example of the German Romantic period, which prioritized the emotions of an individual and advocated for a return to nature and traditional values. This movement resonates thematically with Gone With the Wind, which unfolds in the American Deep South at a time of declining Southern principles and societal transformation. Scarlett O’Hara, at least at the outset of the story, is the quintessential Southern belle and romantic heroine—complex, intense, and idealistic. Above all else, she values her homestead, Tara. Just like the woman in Friedrich’s portrait, in this scene, she surveys the land and finds herself overcome by the emotion it inspires in her.

A film that features an uncannily accurate tableau vivant is John Wayne’s 1960 war film, The Alamo. Wayne recreated John Singer Sargent’s El Jaleo down to the smallest detail. Not only are the set-dressing, characters, and costumes lifted directly from the painting, but the lighting is also an exact replication of Sargent’s masterpiece.

Renoir and Impressionism

Cinema and art have been intertwined since the inception of film. Whether overtly or symbolically, the influence of famous works of art on the medium of cinema is indisputable. On a grander scale, it is possible to identify connections between cinematic movements and artistic developments. Cinema was invented at the zenith of the Impressionist era. This movement had a great impact on cinema as individuals experimenting with this new medium took inspiration from the great French painters like Manet, Monet, and Pissarro. Impressionist filmmakers believed art should not express truths directly, but create an experience that gives rise to emotions that would lead audiences to underlying truths.

The similarities between the outlook of Impressionist artists and Impressionist filmmakers are undeniable. Across both mediums, creators adopted an avante-garde style where suggestion took precedence over anything concrete. This was a response to the transient nature of the early 20th century. Manet and his father, Auguste, heavily influenced the early French filmmaker, Jean Renoir. Many scenes in Renoir’s film Une Partie de Campagne (1936) refer to Impressionism.

New Objectivity and The German Expressionists

Expressionist cinema emerged in Germany in the period between the two world wars. The movement produced masterpieces such as Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), and Fritz Lang’s ground-breaking Metropolis (1927). The cinematography of these films was inspired by the New Objectivity painting movement, an outgrowth of German Expressionism that was dominated by painters like Max Beckmann.

Dadaism and the Surrealists

In the 1920s, the emergence of Dadaism coincided perfectly with that of cinema. Often touted as the first conceptual art movement, Dadaists experimented with various mediums to subvert preconceived notions of what art could or should be. This led to the surrealist movement in both art and cinema. Perhaps the most famous film from this period is Luis Buñuel’s collaboration with Salvador Dalí in Un Chien Andalou (1929). This film exemplifies the fusion of art and film, blurring the lines between dreams and reality and provoking viewers to reconsider the concept of narrative. The script, written in a collaborative effort by Dali and Bunuel, was produced under one stipulation, “not to incorporate any image or idea for which the viewer could come up with a rational, psychological or cultural explanation.”

Adaptations and Homages

Certain filmmakers have taken the link between cinema and famous works of art one step further and developed entire narratives around specific paintings. Take The Mill and The Cross from 2011 for example. Not only was director Lech Majewski inspired by Pieter Bruegel’s masterpiece The Procession to Calvary, recreating it with startling precision on-screen, but he centered the whole narrative of the film around twelve characters pictured in the original painting.

Another film that not only features an exquisite tableau vivant but also bases its story around the original artwork is Agustín Díaz Yanes’ Alatriste (2006). The story takes place in 17th century Spain during the Eighty Years War and recreates a scene from Diego Velasquez’s The Surrender of Breda. The painting depicts the end of the war and shows the symbolic moment when the key of Breda was relinquished by the Dutch and taken back into Spanish possession.

Emotional Landscapes and Symbolism

Filmmakers have also chosen to pay homage to famous works of art through their narratives in more symbolic ways. There are several examples of directors who have taken the emotional resonance of a painting and used it to develop their cinematic world. One such example is Salvador Dali’s Elephants, which depicts spectral, otherworldly elephants, propped up on spindly legs. It is possible to see the similarities between Dali’s painting and Geroge Miller’s 2015 film Mad Max: Fury Road. Miller’s tribute to Dali presents a dystopian dreamscape where shadowy, wraithlike figures roam.

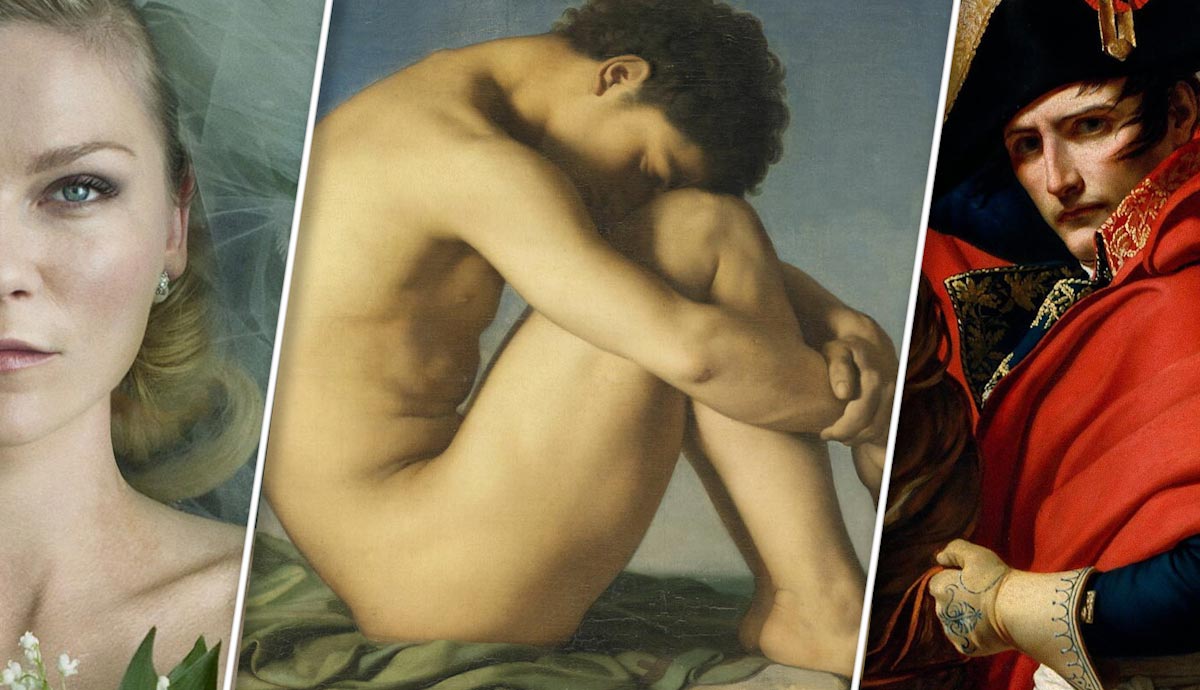

John Everett Millais’ most famous painting, Ophelia, is an illustration of a scene from Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In this scene, Ophelia, driven mad by the murder of her father at the hands of her lover, falls into a river and drowns. Lars von Trier recreates the painting in his film Melancholia (2011), where it acts as a foreshadowing device. There are distinct parallels between Ophelia as depicted by Millais and Von Trier’s Justine, played by Kirsten Dunst.

The film opens with a dream sequence—Justine, in a wedding dress, runs through the forest as the world burns around her. She falls into a river and drifts submissively upstream. Just like Ophelia, she has accepted her fate. Von Trier’s apocalyptic film explores what happens to the human psyche during a depressive episode. This scene sets up Justine for the depression she will experience later in the film by drawing comparisons to the trajectory of Ophelia.

Famous Artworks Inspired Indie Directors Too

Some filmmakers have used their mise-en-scene to reference art in multiple works. Paul Thomas Anderson is best known for his use of Steadicam to choreograph intricate long takes. What is less talked about is how he finds inspiration in famous artworks. His 2015 film, Inherent Vice, shows a boozy Last Supper, replete with pizza and paisley. Considered the most important mural painting of all time, it is perhaps fitting that Anderson should choose this iconic composition to stitch together the threads of his story. And it is not the only biblical reference in the film. Owen Wilson’s character echoes a line from Thomas Pynchon’s original novel, saying: “What was ‘walking on water’ if it wasn’t Bible talk for surfing?”

In 2007’s There Will Be Blood, Anderson looks forward a few centuries to Hippolyte Flandrin’s 1837 work, Young Male Seated Beside the Sea. He uses Flandrin’s most famous painting to construct a compelling visual of Henry Plainview, silhouetted against the shoreline. This pivotal point in the narrative finds Daniel Plainview gripped by suspicion regarding his alleged half-brother. Just moments earlier, his apprehensions were confirmed as Henry failed to recall the peachtree dance of their hometown. Daniel leaving Henry alone on the beach shrouded in shadow, carries profound symbolism. Here, the shadow serves as a poignant manifestation of Henry’s guilt and Daniel’s abiding sense of isolation.

Sofia Coppola is another director who has used paintings to inform her composition. Her film, Lost in Translation, opens with a recreation of John Kacere’s 1973 painting, Jutta, which later appears on the main character Charlotte’s bedroom wall. This simple shot reveals so much about Charlotte’s character; the lingerie she wears strikes a delicate balance between innocence and sensuality, mirroring her inner transition from girlhood to womanhood. With this shot, Copolla captures the essence of Charlotte’s journey and establishes the sense of intimacy that permeates the whole film.

Coppola looked to the Neoclassical era as inspiration for her 2006 film, Marie Antoinette. Jacques-Louis David was famous not only for his paintings but also for his revolutionary ideas, so it is fitting that Coppola incorporated a tableau vivant of his portrait, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, in her film. Marie Antoinette is of course set in 18th-century France and it documents the expulsion of the French royal family. Referencing, Jacques-Louis David is a nod to one of the most influential figures of this period, a man who was central to the revolutionary cause.