In A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf famously posited “that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman.” Many women writers throughout history have sought to maintain their anonymity—be that to preserve their privacy, maintain a distance between their fictional and non-fictional writings, or to evade some of the prejudicial criticisms reserved for women authors—by adopting a male pseudonym. Here, we will look at eight examples of women writers who did just that.

1. George Sand

Born Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil on July 1, 1804, George Sand was the nom de plume under which she published 70 novels and over 50 volumes of other writings (ranging from plays to political works) before her death in 1876. Her prolific output of works was matched by her popularity, becoming more celebrated in Britain than such French male writers as Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac.

In 1831, when she was still an unknown writer, she chose the pseudonym George Sand to improve her chances of success in the androcentric publishing industry. Rather than choosing “Georges” (the male French version of “George”), “George” was somewhat more ambiguous, signifying either the English male form or perhaps a French female form of “Georges.”

This, however, was not the first time Sand had played with gender expression or railed against the limitations that society placed on women. In the 19th century, when French women were required to apply for a permit to wear male clothing, Sand chose to wear male clothing without such a permit. Moreover, she habitually smoked tobacco in public—something not even a permit could excuse in 19th-century France. “George Sand,” according to Victor Hugo, “cannot determine whether she is male or female.”

In her writing, too, Sand was something of a radical. A noted member of the Romantic movement in literature, her writing often rails against the confines matrimony places on women, and she championed women’s causes throughout her life. Though married to François Casimir Dudevant, she had relationships with many men of note (including writers Jules Sandeau and Prosper Mérimée, politician Louis Blanc, and, perhaps most famously, composer Frédéric Chopin) as well as at least one lesbian love affair with the actress Marie Dorval.

2. George Eliot

Mary Ann Evans was born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, at South Farm on the Arbury Hall estate (which her father managed) on November 22, 1819. She became a novelist after publishing her essay-cum-manifesto “Silly Novels by Lady Novelists,” in which she criticized the triviality of contemporary women’s fiction. Under the pseudonym “George Eliot,” she wrote her novels in the realist tradition emerging in Europe, eschewing the lighter, romantic subject matter of many other women writers at the time.

From an early age, she demonstrated a keen intelligence. Her father, believing that she was no great beauty and that, therefore, an advantageous marriage would be unlikely, allowed her an education otherwise not typically afforded women at the time. She boarded at various schools between the ages of five and sixteen, after which she received little in the way of formal education but was permitted to read from the library of Arbury Hall, which she did voraciously.

Also at the age of sixteen, her mother died. Five years later, she and her father moved to Coventry. Here, she was exposed to radical, free-thinking societies and published an English translation of Strauss’s Das Leben Jesu kritisch bearbeitet (The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined), in which Strauss argued that the miracles recorded in the New Testament should be considered as mythical rather than factual.

Following her father’s death in 1849, she moved to London, where she became the assistant editor (in reality the editor in all but name) of the left-wing Westminster Review. In 1851, she met the philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes. Though married, Lewes was unable to obtain a divorce. Nonetheless, she and Lewes lived together from 1854 and considered themselves married to each other.

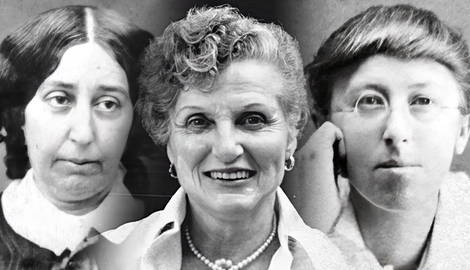

3. 4. & 5. The Brontë Sisters

Charlotte, Emily, and Anne Brontë are world-famous novelists. Perhaps less well-known is that they published under the pseudonyms of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell.

Growing up in an isolated parsonage in Haworth, West Yorkshire, the Brontë sisters received relatively little formal education (aside from short stints at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge for Charlotte and Emily, Miss Wooler’s school at Roe Head for all three, and the Pensionnat Héger for Charlotte and Emily). Their father, however, educated them in subjects such as history and languages, allowing them to read from his library.

Their childhood, then, fostered a love of reading and writing in all three sisters. After discovering some of Emily’s poems in 1845, Charlotte convinced her sisters to produce a joint collection of their poetry. In 1846, their collection was published under their male pseudonyms, selling only three copies.

Despite this, Emily was busy writing Wuthering Heights, Charlotte was working on The Professor, and Anne was channeling her struggles as a governess into Agnes Grey. After only Emily and Anne’s novels were accepted for publication, Charlotte began work on Jane Eyre, and all three novels were published in 1847 under their pseudonyms.

The name Brontë itself was something of an invention on the part of Patrick, their father. Derived from the Irish clan Ó Pronntaigh, the surname was typically anglicized as Prunty or Brunty. Patrick, an Irishman who was then studying at Cambridge University, may have wished to distance himself from his Irish surname. He may have done so in honor of Admiral Horatio Nelson, Duke of Bronte, though he may also have wished to avoid association with his brother, William, who was a wanted man following his association with the United Irishmen movement.

6. & 7. Women in Science Fiction: Andre Norton & James Tiptree Jr.

Alice Bradley Sheldon (the actual name of James Tiptree Jr.) and Alice Mary Norton (who published primarily under the name Andre Norton) were both women writers who chose to publish works of science fiction (a genre still dominated by male writers) under male pseudonyms.

Born Alice Hastings Bradley, Sheldon came from a family of intellectuals. Following the breakdown of her first marriage, she joined the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps as a supply officer. She then went on to join the United States Army Air Forces, earning the rank of major. In 1945, while on assignment in Paris, she married Huntington D. Sheldon. One year later, she was discharged from the military, and her first story, “The Lucky Ones,” was published in The New Yorker under the name Alice Bradley.

After a brief stint in the CIA, she returned to academia, earning her PhD from George Washington University. During this period, she began to publish science fiction short stories under the name James Tiptree Jr. The critic Robert Silverberg—who discerned “something ineluctably masculine about Tiptree’s writing,” which he compared to that of Ernest Hemingway—at least was fooled by her nom de plume.

Alice Mary Norton was born in Cleveland, Ohio, on February 17, 1912. In the wake of the Depression, she dropped out of Flora Stone Mather College of Western Reserve University in 1932 and began working for the Cleveland Library System, where she remained for the next 18 years.

In 1934, she published her first novel, The Prince Commands, being sundry adventures of Michael Karl, sometime crown prince & pretender to the throne of Morvania, and legally changed her name to Andre Alice Norton. It was only in 1958, however, after publishing 21 novels, that she was able to become a full-time writer.

8. Vernon Lee

Vernon Lee was the nom de plume of the writer Violet Paget, though she also went by her adopted name in her personal life. Best remembered for her works of supernatural fiction and aesthetic theory, she was also a feminist, pacifist, musician, and an early disciple of Walter Pater. Like George Sand, she also dressed in typically male clothing—à la garçonne—and, though she resisted the term lesbian, she had long-term relationships with women, including fellow writers Mary Robinson, Clementina “Kit” Anstruther-Thomson, and Amy Levy.

Though she wrote primarily for an English-speaking readership, Lee was born in France and spent most of her life in continental Europe. Though she traveled widely, she favored Italy and spent her longest stretch just outside Florence. She drew on her travels to pen myriad essays on her experiences in Italy, France, Switzerland, and Germany. Unlike most travel writers, however, she sought to delineate her own subjective experience of a place and the psychological impacts it had on her personally.

In collaboration with Kit Anstruther-Thomson, she pioneered “her own version of ‘psychological aesthetics’” by connecting aesthetics to such “bodily reactions” as “eye movements, pulse and heartbeat, [and] muscle tension,” as Vineta Colby explains (see Further Reading, Colby, p. 139). Her pacifism and open disapproval of the First World War meant that her work was sidelined, and she fell into obscurity before feminist scholars set about reviving her work in the 1990s.

From science fiction to aesthetic theory, the women writers listed here all found freedom within a patriarchal society to write under male pseudonyms. In so doing, they circumnavigated society’s gender restrictions and produced some of the most loved literary works of our time.

Further Reading:

Colby, Vinetta, Vernon Lee: A Literary Biography (Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2003).

Ingham, Patricia, The Brontës (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Woolf, Virginia, A Room of One’s Own (London: Penguin, 2004).