The American Civil War ended in the late spring of 1865 with a decisive Union military victory. Despite being defeated militarily, the former Confederacy made no effort to change its treatment of Black people. Slavery was formally eliminated with the Thirteenth Amendment, which all former Confederate states were made to ratify, but Southern states quickly implemented “Black Codes” to try to subjugate formerly enslaved people.

Setting the Stage: Slavery in the South

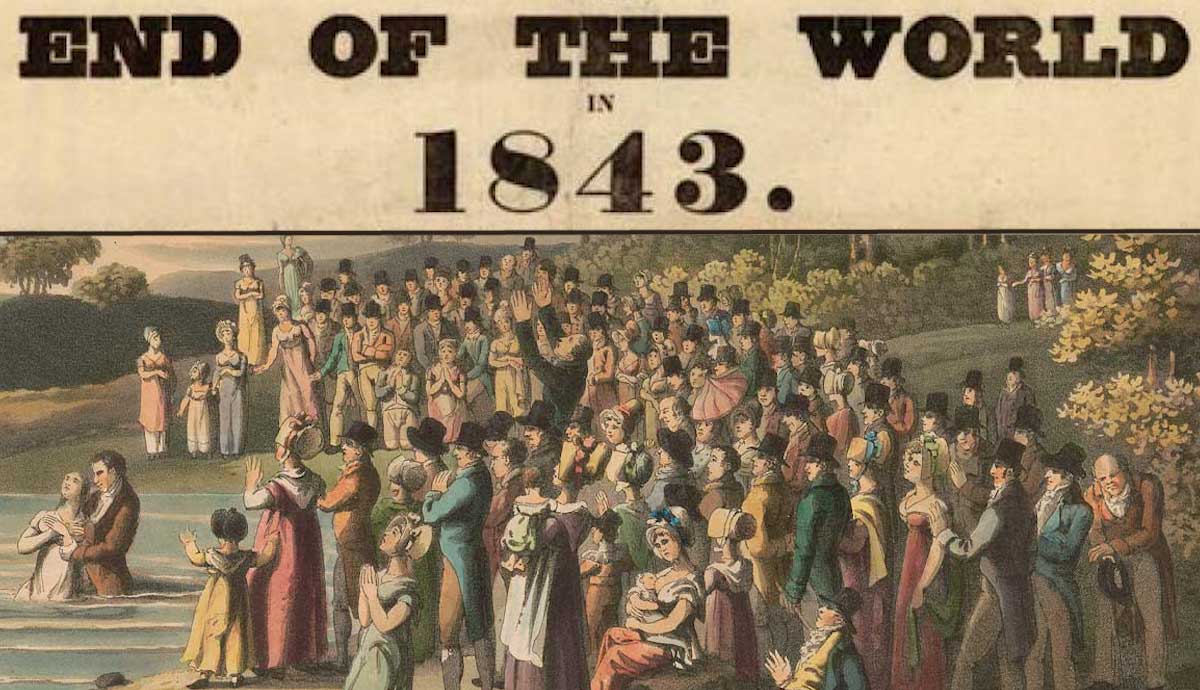

For the first eighty years of the American republic, slavery was a controversial institution. Primarily, slave states were in the South and provided agricultural labor. By the 1840s, the agrarian economy of the South relied heavily on slave labor. Tensions over slavery began to increase during this decade, influenced by the Second Great Awakening religious movement that opened many Americans’ eyes to the evils of forced bondage. This greatly expanded the abolition movement to ban slavery. When new territory was added to the United States after the Mexican-American War, abolitionists clashed fiercely with proponents of slavery.

To keep the peace, Congress and a series of one-term US presidents tried to balance the addition of slave states and free states. The Compromise of 1850 added California as a free state but let other new territories choose their slavery status and increased the powers of Southerners to recapture escaped enslaved people. In 1857, proponents of slavery seemed to win the upper hand when the US Supreme Court ruled that Black people were not citizens of the United States, tacitly approving slavery and preventing Black people from suing for their rights. The Dred Scott decision set the stage for a political reckoning since the courts would not end the institution of slavery.

Setting the Stage: The End of Slavery

The reckoning came less than four years later when anti-slavery Republican presidential nominee Abraham Lincoln won the White House in a four-candidate race. Outraged at Lincoln’s victory, which he achieved with no electoral votes from the South, several Southern states seceded from the union and created the Confederate States of America in early 1861. In April, Confederate forces attacked the United States military at Fort Sumter, South Carolina, beginning the long and bloody American Civil War. In September 1862, to punish the Confederacy for its continued rebellion, President Lincoln made the Emancipation Proclamation: all enslaved people in states still in rebellion against the United States as of January 1, 1863 would be legally considered free.

Unfortunately, no Southern states ended their secession peacefully. Slavery was ended by force as the Union slowly retook Confederate territory, with enslaved people often fleeing toward Union lines to win their freedom before they could be moved deeper into the South. Ultimately, slavery was finally ended in June 1865 when Union troops finally reached southern Texas. On June 19, 1865, a contingent of Union soldiers landed in Galveston, Texas and presented orders to free the enslaved people in the state. Juneteenth is considered the official end of slavery in the United States, and the date has since become a federal holiday.

The South After the Civil War: Black Codes

Although militarily defeated, the South was not willing to voluntarily change its treatment of Black people. The states, although forced to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution to abolish slavery, quickly created laws and policies to keep former slaves in positions of forced labor. These Black Codes were laws to punish unemployment and vagrancy with forced labor…effectively re-enslaving Black people. Across Southern states, which were militarily occupied by the federal government, white voters swiftly voted ex-Confederates back into office.

In the most restrictive states, Black people were arrested and forced to do forced labor if they could not produce written contracts of employment on an annual basis. Employers could deny these documents, often to avoid having to pay for labor received. Republicans in Congress, angered by the Black Codes, began passing civil rights acts. When Southern Democratic US President Andrew Johnson vetoed these civil rights acts, a two-thirds majority of each chamber of Congress overrode the veto.

1868: Fourteenth Amendment Ratified

More help was needed to ensure the rights of Black people in the South, so Congress pushed on and passed the Fourteenth Amendment. This amendment granted citizenship to all formerly enslaved people (and everyone born in the United States) and famously stated that all citizens shall be treated equally under the law. Importantly, this amendment gave formerly enslaved people the same citizenship status as white people. Most Southern states refused to ratify this amendment, but the Reconstruction Act of 1867 made ratification a requirement for those states to be readmitted to the union.

There was strong resistance in the South to give equal rights to Black people, and many deemed the Fourteenth Amendment invalid because it was allegedly only ratified under coercion. Since the Fourteenth Amendment did not specifically mention voting rights, these rights were still denied. As a result, Congress still needed to act. Fortunately, thanks to the recent election of Republican presidential candidate Ulysses S. Grant, famous Union general during the Civil War, Republicans in Congress had enough political power to quickly push through another constitutional amendment in February 1869.

1870: Fifteenth Amendment Ratified

Again, Southern states did not wish to ratify this new amendment. However, Congress swiftly decreed that ratification was a requirement for readmission to the union. The Fifteenth Amendment was ratified on March 30, 1870, and explicitly stated that voting rights shall not be “denied or abridged” on the basis of race. Eagerly, many Black men began to vote for the first time, giving formerly enslaved men a degree of political power for the first time in American history.

Unfortunately, the amendment was broad and ambiguous, leaving a giant loophole for states to abuse. In the US Constitution, voter registration was left to the states, giving each individual state the ability to pass laws regarding when and how people could register to vote. For a brief period, Black men (women would not be granted voting rights in all states until the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920) were able to elect their own to political offices in the South. Between ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 and the end of Reconstruction in January 1877, up to 2,000 Black men were elected to political office.

Early 1870s: Southern Resistance to Black Suffrage

Southern states initially did not discover the legal loopholes they would later use to deny voter registration to many Black men. However, many former Confederates united to use violence and intimidation to limit the Black vote through radical groups like the Ku Klux Klan (KKK). “The Klan” conducted large rallies to intimidate Black people—and other minorities—away from the polls. They also engaged in attacks on Black people who voted to send signals to others who might support the pro-civil rights Republican Party. State governments took no action against these attacks.

After their intimidation helped the Democratic Party win elections in 1870, the Ku Klux Klan began to erode as the federal government intervened once again. The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 allowed US President Ulysses S. Grant, a proponent of civil rights for formerly enslaved people, to use the military to take control of civil affairs in states that were not doing enough to combat the KKK. After Grant utilized this power in South Carolina, other Southern states began prosecuting the Klan. Prominent members of the Klan, many of whom were considered respectable leaders in the community, ceased their activities to avoid consequences.

Literacy Tests

In 1890, Southern states introduced a formal tool to prevent Black men from voting: literacy tests. Beginning with Mississippi, the South added literacy tests and poll taxes to its state constitutions to disenfranchise voters who might threaten the dominance of the Democratic Party. Because the literacy tests were “race-neutral” and theoretically applied to all voters, this allowed states to claim they were following the Fifteenth Amendment. In 1898, the US Supreme Court agreed, upholding literacy tests. To allow poor whites to vote, states could selectively use the grandfather clause to exempt them from literacy tests if their grandfathers had been registered to vote by a certain date.

Literacy tests were so effective at limiting the Black vote because they were created to be arbitrary (able to interpret any way) and controlled entirely by local authorities. Thus, in most places in the South, Black voters were deemed “illiterate” regardless of their actual intelligence or literacy skills. Although the Supreme Court struck down the grandfather clause as unconstitutional in 1915, the balance of power was permanently shifted against Black voters because many illiterate white voters had already registered. For decades, segregation in the South was unchallenged because Black citizens could not vote. Many Southerners argued that literacy tests were a valid tool to protect democracy, but critics saw that they were plainly racist in application.

Voting Rights Act of 1965

With many Black citizens disenfranchised from voting when the Civil Rights Movement began in the 1950s, progress was slow. Despite the Fifteenth Amendment asserting that the right to vote should not be limited on account of race, states had effectively used literacy tests to prevent most Black men and women from voting. As little as three percent of voting-age Black people were registered to vote in 1940. When the Civil Rights Movement began, a major component was voting rights. Organized drives were made throughout the South, often using volunteers from the North to register Black voters despite local opposition.

Violence was inflicted on many Black people who tried to register to vote or register others to vote in the early 1960s. However, voter registration drives were successful, and the rate of Black voter registration significantly increased by 1964. This boosted optimism to continue the drives and protests against voter suppression. When Alabama authorities attacked peaceful protesters in early 1965, television coverage rallied national support for protecting Black voting rights. US President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to push through a Voting Rights Act, which he signed on August 6, to finally and fully enforce the Fifteenth Amendment. The Act banned the use of literacy tests and temporarily replaced local voter registration clerks with federal employees.

Race-Based Gerrymandering in the South

Another part of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 dealt with redistricting of legislative districts. Both US House of Representative districts and state legislative districts are redrawn periodically by state legislatures to provide for equal representation for voters. Prior to the mid-1960s, however, redistricting in many states was done blatantly to advantage the political party in power. In the South, this meant redistricting to limit the power of Black voters. This meant that, even as more Black citizens were able to vote, their votes had little power. Typically, predominantly white suburbs were made centers of districts so that predominantly Black urban areas were divided up, preventing any majority-Black districts.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 banned race-based redistricting and allowed the federal government and private citizens to sue states for alleged violations of this rule. Several lawsuits have since been filed against states for alleged race-based gerrymandering. Initially, many states and counties were subject to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, which required them to get pre-clearance from the federal government for redistricting. Most Southern states were required to get federal approval for their redistricting due to a proven history of race-based gerrymandering (a pejorative term for redistricting). The formula used by the federal government to approve Section 5 redistricting was ruled unconstitutional in 2013, but Section 5 itself may still be legal.

Alleged Voter Suppression Today

Many people allege that voter suppression, a potential violation of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, remains a significant issue in the United States. Redistricting is still frequently criticized in many Southern states for diluting the voting power of minorities. In recent years, however, the federal government has allowed these states to redistrict according to their original plans. In 2018, for example, the US Supreme Court ruled that Texas’ controversial redistricting was only partisan-motivated and not race-motivated, thus making it legal. Critics argue that the lack of racist motive does not mean minorities’ voting power is not being weakened by such partisan redistricting.

Claims of voter suppression now focus on voter roll purging and threats of prosecution for illegal voting. Conservative states have been accused of intentionally trying to disenfranchise lower-income and minority voters by aggressively purging voters who miss voting in recent elections, thus increasing the power of wealthier voters who can easily make it to the polls each time. Aggressively questioning voters about their voting status and threatening prosecution for illegal voting is sometimes considered voter intimidation, with critics claiming that conservative states are using such tactics to frighten low-income and minority voters away from the polls.