The independence movement in America featured the patriots (sometimes called Whigs) against the loyalists (a.k.a. Tories). The Whigs wanted to separate from Britain, but the Tories wanted to maintain the royal connection. Caught in the middle were many undecided, ambivalent, and noncommittal Americans. Writers, speakers, painters, and publishers that favored independence adapted imagery and messaging from the First Great Awakening (1730s-1750s) in hopes of persuading more people to support their cause.

Pointing Toward a New Light

The Great Awakening was a renaissance of Protestant religious fervor in America and across Northern Europe. It grew from a paralleled resistance to secularism on one hand and the quite somber tenor of traditional church services on the other. In a word, this new manner of spiritual expression was evangelism. The message appealed to the heart, not the head, and it took hold throughout the Colonies just before the “Shot Heard ‘Round the World.”

In America and Britain, by the eighteenth century, the three principal figureheads behind the growing popularity of evangelism were Jonathan Edwards, Gilbert Tennett, and George Whitefield. They were itinerant preachers who traveled from place to place and emphasized the individual’s responsibility to choose between good vs. evil — and the joys that came from following the Christian faith. Due to the collective influence of these early evangelists, religious revivals became commonplace on both sides of the Atlantic. The First Great Awakening also launched the start of new denominations within Protestantism, including Methodism and Baptism. Members of these newer churches were known as “New Lights.”

Behold! The promoters of American independence seized on the notion of New Light. To them, it was the perfect metaphor for the formation of a new style of government—self-rule, or republicanism, as opposed to monarchy. Republicanism itself was not new, having been established in ancient Rome and Athens. But it was a new idea for the New World. Even as early as the 1740s, the public recognized political tyranny as “sinful” and civil liberty (self-rule) as “virtuous,” even “angelic.”

King George III: Tyrant of all Tyrants!

Revivalists had often used terms like liberty, freedom, virtue, tyranny, bondage, and slavery in the spiritual sense. The promoters of American independence appropriated those same words and applied them to the political context. Revolutionaries such as Congressman John Adams, Virginia Legislator George Mason, and writer Thomas Paine made “fruitful use of the capital which these terms had acquired in the revival,” writes Professor Mark A. Knoll of Notre Dame University in A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada (2019).

By early 1776, the most powerful statement in support of the patriot cause was Thomas Paine’s Common Sense. Paine’s book, and later the Declaration of Independence itself, openly called George III a tyrant (devil) and a promoter of tyranny (sinfulness). In fact, Paine frequently alluded to scripture in arguing the case for American independence, just as evangelists during the Great Awakening evoked scripture in arguing the case for spiritual salvation.

“[T]he will of the Almighty, as declared by Gideon and the prophet Samuel,” he writes, “expressly disapproves of government by kings. All anti-monarchical parts of scripture have been smoothly glossed over in monarchical governments, but they undoubtedly merit the attention of countries which have their governments yet to form.”

In another section of Common Sense, Paine declares, “Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.”

The late historian William G. McLoughlin of Brown University believed the American Revolution, as a political movement, was so deeply embedded in the soil of the First Great Awakening that it can be argued it was the natural outgrowth of that profound and widespread religious movement.

The Devil is in Control!

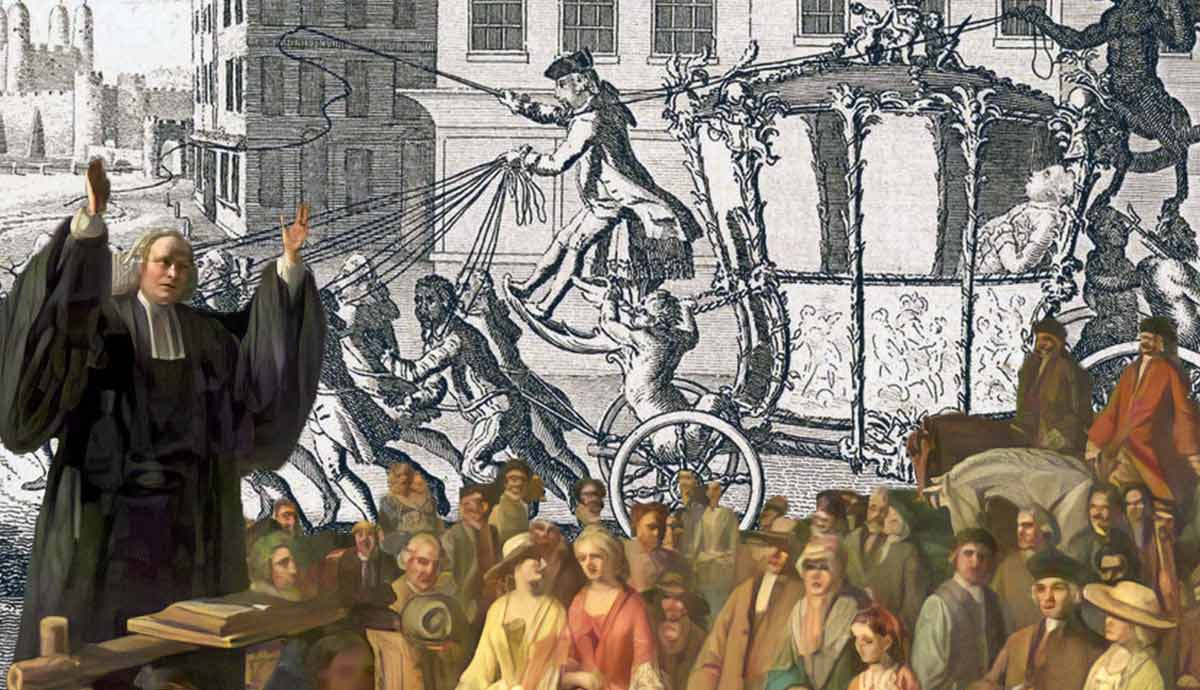

The illustration above is an excellent example of the campaigning being disseminated in the press on both sides of the Atlantic just before and during the Revolutionary War (1775-1783). The devil, a universal symbol of evil often evoked during the Great Awakening, was juxtaposed with a political message.

In this instance, the Devil is behind the Coach controlling Prime Minister Lord North (in office 1770-1782), who is in the driver’s seat. North, in turn, controls the group of gentlemen pulling the Coach, e.g., the king’s friends in the Commons. George III, meanwhile, sleeps peacefully in the rear of the Coach as a passenger.

In America, the image of the king-as-devil was quite radical, given that many American colonists still thought of themselves as loyal, law-abiding British subjects. In July 1775, just a year before the Declaration of Independence was approved and some weeks following the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775), moderate Congressmen led by Pennsylvanian John Dickinson sent the Olive Branch Petition to George III. In the Petition, they tried to convey the colonists’ “tender regard” for the Empire and assured the king that Americans remained “faithful subjects…of our Mother country.”

Some Britons might have argued that George appeared asleep during his reign, meaning he didn’t seem in control or that he lacked interest, but others would counter that the first Hanoverian king to speak native English and avoid long visits to Hanover slept with one eye always open. Although George was not an autocratic king (since the British Constitution forbids autocratic monarchies), it is true he manipulated his ministers to get what he wanted. He drew a heavy line in the sand with respect to the rebelling colonies in America, and he cajoled Prime Minister Frederick North (in office 1770-1782) and friends into supporting his ideas.

George wanted to quash the rebels in order to preserve his honor and that of Great Britain. Lord North tried to resign several times over how the crisis in America was being handled, but the king refused to accept his resignation—until after the loss at the Battle of Yorktown (Oct. 19, 1781). The British Royal Household states: “Being extremely conscientious, George (III) read all government papers and sometimes annoyed his ministers by taking such a prominent interest in government and policy.” Britannica is even more revealing: “George… had tenacity, and, as experience matured him, he could use guile to achieve his ends.”

Hark! The Herald Angels

In this rare print attributed to American artist Henry Dawkins, both an angel and a devil appear within the context of the Boston Tea Party and debate over Parliament’s 1773 Tea Act. The map shows Britain on the left side and America on the right. In Britain, representatives of the East India Company, British lords, and Beelzebub (the prince of all devils) discuss the Americans’ resistance to the tax on tea. At their feet are boxes of tea and a plan for a warehouse in America. Above them, Britannia complains to the “Genius of Britain” that “the conduct of those my degenerate Sons will break my Heart.”

On the right side, a woman representing America leads a group of Native American men representing the Sons of Liberty into battle. Below them, a group of men (loyalist merchants) in mourning garments complain that patriotic resistance to the Tea Act will disrupt their plans. Above them, at the top, angelic figures representing Liberty and Fame praise the Sons of Liberty. “Behold the Ardor of my sons and let not their brave Actions be buried in Oblivion.” Portraying the Sons of Liberty (ardent patriots) as angelic is a direct application of a religious image to the Whig cause.

Avoiding the R-word

In Common Sense and in the Declaration of Independence, there is no mention of the ongoing “revolution” in America. The descriptors “American Revolution” and “Revolutionary War” came along generations after the events themselves. Why was the R-word avoided during that time? In the public consciousness, especially among the Founding Fathers, “revolution” conjured up radical images of the English Civil Wars (1640-1660) and the Glorious Revolution (1688-89). These were periods when mobs, anarchy, civil disorder, violent force, and abrupt change ruled the day.

For the founders of the American government, revolution meant all those negative things. That’s why no contemporary spoke of it. George Washington himself was the first to condemn unruliness. All the dominant Whigs in government, including Washington, Jefferson, and Patrick Henry, never wanted the independence movement to seem like another English civil war. Nor could the gaining of independence in America be seen as an opportunity for the less privileged to launch anarchy. The founders viewed chaos, no matter if it was well-intentioned, as the enemy.

This restraint may have also sprouted the limitations that were inherent in the system that developed. Author Joseph J. Ellis summed it up in his book, The Cause: The American Revolution and its Discontents, 1773-178 (New York, 2021): “The French Revolution is admired for attempting to implement its radical agenda all at once and failing. The war for American independence is criticized for deferring its full promise and succeeding.”

Divine Freedom & Reaffirmation

In order to keep the transition from constitutional monarchy to republicanism peaceful and smooth, optimism had to prevail. How was that achieved? Independence was promoted as synonymous with freedom and enlightenment. As Paine wrote in Common Sense: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again. A situation, similar to the present, hath not happened since the days of Noah until now. The birthday of a new world is at hand…”

He was emphasizing a glorious, youthful acquisition of a more just system of government. Surely, many believed, this movement was ordained by God as a reaffirmation of divine freedom, a weaning from the corruption of monarchy.

One of the first Europeans to employ the term “Revolution” for what took place in America in a positive light was the Welsh minister and pamphleteer Richard Price. In 1783, in a personal letter to American Benjamin Rush, Price wrote, “The struggle has been glorious on the part of America; and it has now issued just as I wished it to issue; in the emancipation of the American States and the establishment of their independence… I think it one of the important revolutions that has ever taken place in the world.”

On a final note, the American Revolution opened the door to a broader political franchise than had hitherto been accomplished. However, women and other disenfranchised persons were not included in the political system. Over the past 250 years, under-represented Americans have worked hard to be seen, heard, respected, and included. Progress, however slow and painful it has been, could only have happened with the foundation of the living historical documents that the founders established. In the United States, the promise remains out there for all people to have a voice and share in freedom and liberty.