summary

- Gunpowder, originating in 9th-century China, was crucial for the development of early firearms, transforming warfare.

- The first true guns, hand cannons, appeared in China around 1280 CE, later spreading to Europe by the 14th century.

- The arquebus, with its matchlock mechanism and improved design, marked a significant advancement in personal firearms by the late 15th century.

- The invention of the wheellock in the early 16th century introduced self-ignition, followed by the musket, which rendered plate armor obsolete.

- Modern firearms, including machine guns and assault rifles, evolved rapidly, significantly impacting 20th and 21st-century warfare, and firearm technology has continued to evolve past gunpowder-based propellants.

Although gunpowder first emerged in ancient China as an alchemical health treatment, it was its application in warfare that shattered the medieval world. In many ways, it was the quintessential substance of the rapidly approaching modern era, with cultural exchange, scientific experimentation, and mass warfare all bound up with its history. This article will ask: when was the first gun invented? It will also explore the development of guns and personal firearms, and how they changed armed combat.

Gunpowder: Lifeblood of the First Guns

The critical ingredient for the rise of the first guns in the Renaissance era was gunpowder. Most people with an interest in Medieval history know that gunpowder was an invention from Medieval China — one of the “Four Great Inventions” that Chinese scholars perfected in the Imperial age. The other three were the compass, paper, and printmaking, which were all also key components of the technological revolution that characterized Renaissance Western Europe. It’s important that we understand that the Renaissance period was a period of dialectical interface between the West and Middle Eastern and East Asian cultures, where a constellation of technologies, goods, and ideas were exchanged back and forth, shaping all of these societies and changing world history. Gunpowder was, therefore, the archetypical technology of its time.

Chemically, gunpowder is a mixture of sulfur, carbon, and potassium nitrate (usually known as niter or saltpeter). It is a low explosive, as distinct from a high explosive, that burns comparatively slowly by modern standards. But to medieval people, this must have been the very crux of alchemy itself — the creation of fire, smoke, and violent force from the application of a small flame to some inert powders.

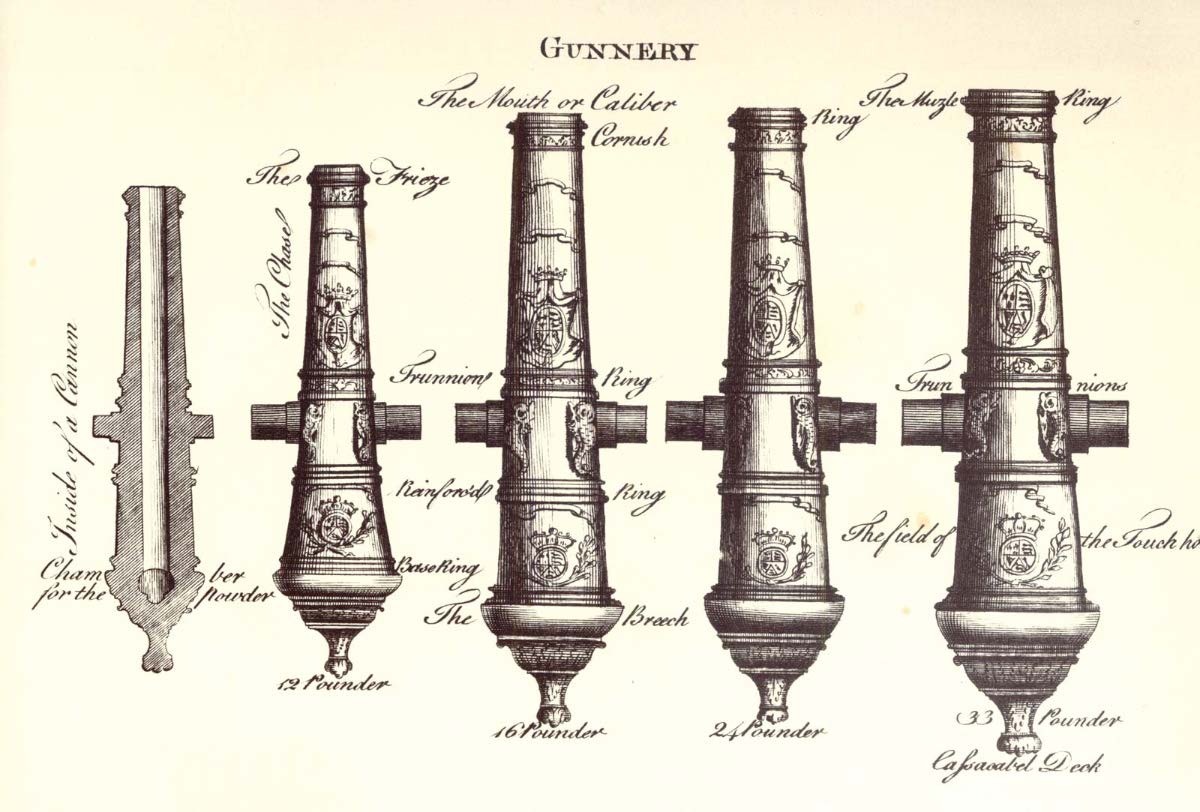

Illustration of Canons, from the first edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica, late 18th century. Source: Britannica

Gunpowder was invented in China sometime in the mid-1st millennium CE, possibly as early as the late Eastern Han dynasty. It was likely discovered as a by-product of alchemical experimentation — Taoist texts from the era demonstrate a preoccupation with transmutation (changing the chemical properties of materials, e.g. “turning lead into gold”), and saltpeter was a frequent ingredient in these experiments.

The earliest cast-iron reference to gunpowder appears in 808 CE, in which the text Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe (真元妙道要略) gives a recipe of six parts saltpeter, six parts sulfur, and one part birthwort herb. Initially applied to courtly firework displays, this substance was known as “fire medicine” (“huoyao” 火藥), reflecting its association with Taoist medicinal experimentation. Before 1000 CE, this early gunpowder was applied militarily, and used for slow-burning fire arrows. The refinement of the art of powder-making resulted in much more powerful explosives, which were soon applied militarily as explosives and rocket propellants.

The ancestor of the first guns appeared in the first half of the 12th century, with a weapon known as the “fire lance.” This was a spear with a gunpowder charge in a bamboo tube attached near the end of the shaft. At first, these were merely powder charges that would shoot a plume of directed flame, but later they were also loaded with fragmentary debris like broken pottery and iron pellets. It was used as an impact weapon, like a single-use short-range flamethrower shotgun. However, it often isn’t considered a true firearm, as it did not use the explosion to drive the projectile along the tube — the debris was merely “blown” forward along with the fire.

Chinese Hand Cannon: When Was the First Gun Made?

What we might seriously consider as the first guns were hand cannons that appeared in China in the late 13th century. Chinese scholars have debated the historical literature extensively, interpreting surviving texts and depictions in various ways — but a safe date for the earliest true cannon is likely 1280 CE. Emerging from a milieu of experimental gunpowder weaponry like the fire lance, grenades, and bombards, the Chinese hand-cannon was a simple tube with a bulbous base, made from cast bronze (and later iron), often around a 1-inch bore and with a characteristic bulbous ignition chamber at the base to withstand the expansion of the powder explosion. Sometimes, it had a socketed wooden handle at the base to permit it to be carried, but just as often, it did not.

The earliest example is the Heilongjiang hand cannon, discovered in 1970, and dated no later than 1288 CE. Contemporary historical records talk of “fire tubes” (huotong, 火筒) being used by government troops in action against rebels in the region. The hand cannon had no firing mechanism beyond a touch-hole, a small hole that accessed the ignition chamber and permitted the lighting of the powder with a spill. While these hand cannons were doubtless devastating weaponry, they were much more costly and unwieldy than a fire lance, weighing 10 lbs (4 kgs) or more. Both weapons remained popular simultaneously in China throughout the Late Medieval era. These were without a doubt terrifying weapons, which, according to the 14th-century text Yuanshi, sowed “such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other”.

The First Guns in the West

The first guns in Western Europe appeared in the second quarter of the 14th century, around 1330 CE. Various works from this period began to depict what we might think of as “cannons,” such as the image above of a large bolt-throwing gun from Walter de Milemete’s 1326 work De Nobilitatibus Sapientii Et Prudentiis Regum. Gunpowder had been known in Western Europe from the High Middle Ages, likely having been spread along the Silk Road and by Chinese engineers employed by the Mongols; they had penetrated into Eastern Europe in the 1270s CE — but serious development of early guns did not begin until a short while after the emergence of hand cannons in China. There is very little evidence for an independent invention of gunpowder weaponry in Western Europe. Although a German scholar called “Berthold Schwarz” (Berthold the Black) was frequently credited with its invention from the 15th century until the Victorian period, modern scholarship regards his existence as wholly legendary.

By the third quarter of the 14th century, hand cannons were widespread in European armies. Accounts of the Battle of Crecy (1346 CE) contain some early mentions of gunpowder weaponry, including small-caliber hand cannons, larger cast-metal bombards, and even ribauldequins which could fire volleys of iron bolts. Archaeologists have even unearthed several iron balls of matching caliber from the battlefield. Despite initial suspicion and slow adoption, by the early 15th century the Islamic world had also embraced firearms, with the Ottoman janissaries becoming a feared group of crack troops armed with hand cannons and grenades.

The Gunpowder Age Dawns

As with all new weaponry, the first guns did not upend conventional military wisdom overnight: there was a period of tactical experimentation and technological refinement in order to achieve the potential of the technology. Hand cannons were far slower to load than a bow, and even a crossbow. They were temperamental and unusable in poor weather and were frequently a danger to their users. Their effective range was a fraction of other missile weaponry. But their destructive power was evident from the first.

Up until this point, artillery was merely a scaled-up version of hand firearms (i.e. the bombard was merely a large hand cannon), it was at this point that artillery and firearms parted ways. Cannons would go on to transform Renaissance warfare, giving commanders the ability to puncture walls and destroy castles, even fundamentally changing the whole construction of defensive fortifications to combat their immense power. The first guns in Europe began to give way to more advanced forms of weaponry, which would have their own world-shattering impact. We shall examine a few of them below.

The Arquebus

The first major development of the hand cannon was the arquebus. The word arquebus comes from the Dutch haakbus, meaning “hook gun”, referring to the hook on the underside of the weapon which was used to prop the weapon up on walls, or, in the open field, on a forked rest. It was one of the first guns to draw together all of the features that we commonly associate with the first guns of the Renaissance by the end of the 15th century. Gone was the hand cannon’s bulbous firing chamber: improved metalwork meant that the smoothbore barrel could be straight.

It now had a priming pan, a secondary scoop on the exterior of the gun that was filled with powder in order to ignite the main charge within the barrel. It had a proper firing mechanism called a matchlock, the earliest form of trigger. This was a hinged arm fitted with a smoldering piece of tow rope — pulling the trigger would bring the end of the rope to the priming pan. It even had a simple wooden stock, likely inspired by contemporary crossbow design, permitting the gun to fire with far greater accuracy and mobility from the shoulder. These remained inaccurate and finicky, with many soldiers complaining that their slow matches would go out in the rain — but they were a vast improvement over cumbersome hand cannons.

The first force to employ the arquebus in large numbers was the Black Army of Hungary at the close of the 15th century, of whom one-in-four soldiers were arquebusiers. The legendary German-speaking mercenaries known as Landsknechts began to use mixed-unit tactics, with arquebusiers and longsword wielders mixed into pike squares. The adoption of large numbers of these first guns permitted the development in this era of firearm tactics, such as the volley fire, which was pioneered independently by Chinese and Ottoman generals.

The Wheellock

An enormous step forward for the first guns came with the invention of the wheellock. Hitherto, all of these early firearms had been lit by some external source of ignition — either a taper dropped into a touch-hole, or a slow match clamped in a trigger mechanism. The wheellock, which appeared in the early 16th century, was the first gunpowder weapon to be self-igniting. It achieved this with an elaborate spring-loaded mechanism that would grind a toothed cog against a piece of pyrite to generate sparks — exactly like a modern cigarette lighter.

Once wound and loaded, a wheellock weapon could be fired with one hand quite easily, and barring complete mechanical failure there was very little chance they would go off accidentally. The major drawback was that they required enormous skill and cost to manufacture — and so they were mostly made as fowling pieces for wealthy patrons, although several examples we have were clearly made as early military pistols.

The Musket

The musket, which emerged in the middle of the 16th century as a heavier variant of the arquebus, ultimately spelled doom for the steel armor of the Late Middle Ages. With the innovation of the snaphance lock (a forerunner of the well-known flintlock that developed from the wheellock to strike its own sparks) muskets became portable, reasonably reliable, and simple to manufacture. Where even the arquebus was unwieldy and inaccurate, muskets could now be fielded as an independent force.

Experiments with replicas of early muskets have shown that they could puncture 4mm of steel. While there was a constant arms race between steel armor and the first guns throughout the Late Middle Ages, the musket was the trump card. It made contemporary forms of all-encompassing plate armor more or less irrelevant, and the armored knight of the Renaissance era was rapidly relegated to the tournament field.

Personal body armor did not disappear overnight, but it changed in form and became much thicker: there is evidence, particularly among cavalry armor, that demonstrates attempts to make bulletproof helms and breastplates. But many troops — particularly poorer soldiers — began to discard their increasingly cumbersome armor entirely, ushering in the post-armor age of Early Modern warfare, fought in uniform jackets and breeches rather than chainmail and plate.

Modern Guns and Warfare

Once the musket was developed, the evolution of guns as military weapons increased in speed. Handguns, such as revolvers that can fire multiple bullets before reloading, started to be developed in the 17th century. However, they only became popular when Samuel Colt produced his version in 1835.

During the American Civil War, soldiers used early machine guns known as a Gatling gun. Invented in 1862 by Richard Jordan Gatling, the Gatling gun used a hand-crank mechanism to shoot rapid-fire. Not long after, the invention of smokeless gunpowder led to the development of the Maxim gun in 1884. Unlike hand-cranked Gatling guns, Maxim guns were recoil-operated. They were widely used in the Spanish-American War (1898) and the South African Boer War (1899–1902).

While the Maxim machine gun was still used in both World Wars, the demand for better weapons saw the development of assault rifles, which can switch between automatic and semiautomatic firing. German inventor Hugo Schmeisser developed the first assault rifle during World War II, the “sturmgewehr” 44. As the Second World War raged on, Russian inventor Mikhail Timofeyevich Kalashnikov developed the now-famous automatic Kalashnikov or AK-47.

The introduction of machine guns was one of the main reasons why World War I was so much more deadly than the wars that had gone before. While the American belief in the right to bear arms and defend one’s self, family, and country dates back to the Revolutionary War, gun culture reached new heights following WWII, as did opposition to guns. The technology has also moved forward quickly since then. Modern guns are almost unrecognizable from their ancient counterparts. Modern guns don’t even use gunpowder as a propellant.