The term Found Object Art refers to artworks that were created from already existing functional objects, either purchased or literally found by an artist. The use of found objects became widespread in the 20th century and reflected the transforming relationship of artists and their audience with the material world around them. With the rise of mass consumption of cheap disposable goods, these goods became accessible artistic materials with clear and inclusive contexts of use. Read on to learn more about found objects in art.

Before Modern Era: Found Objects as Curiosities

The term Found Object or Found Object Art usually refers to art being made from already existing objects that have a practical purpose. Reappropriated by artists as artistic materials, they rarely transform beyond recognition, usually retaining their appearance and at least some of their physical properties. Found object art often relies on discarded materials unfit for their practical use. However, many artists deliberately purchased their objects to build a relationship between a work of art and its contemporary consumer practices.

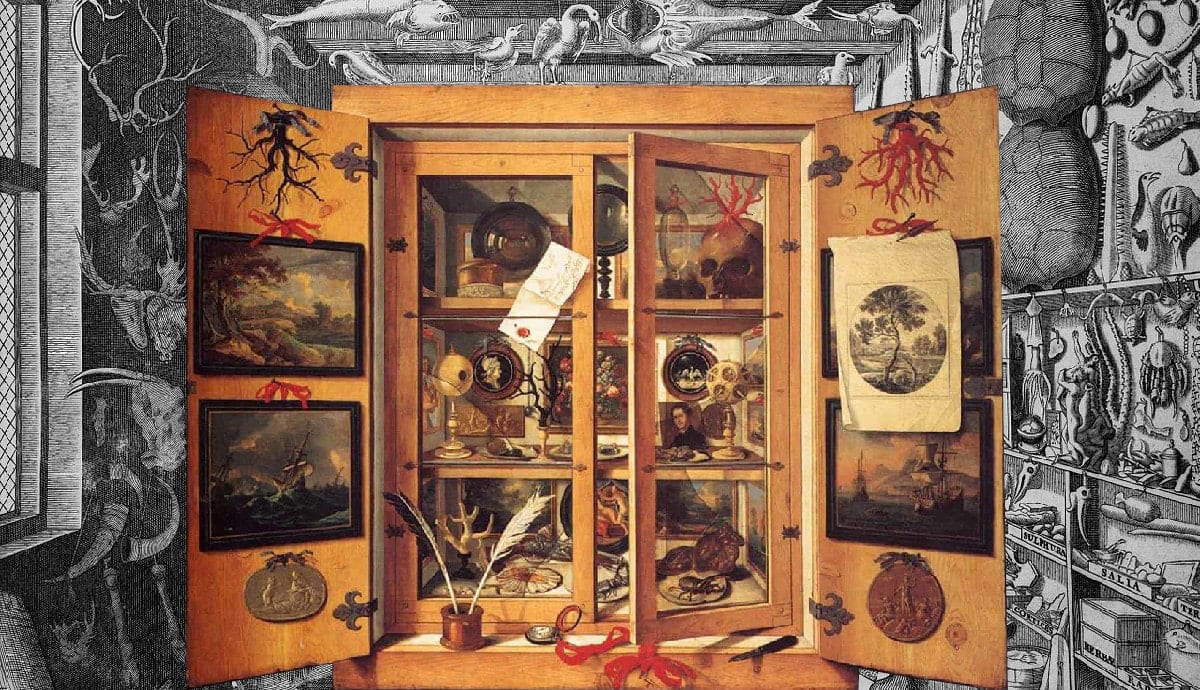

Found Object art is widely considered to be an invention of modernity. Before the 19th century radically transformed our perception and expectations of art, an artwork was regarded as something meticulously crafted not from thin air, but from raw material such as pigment, stone, or metal. However, found objects were nonetheless present in culture, but mostly in the form of collections of curiosities. Educated Westerners collected natural objects, artifacts from Asian and African cultures, as well as animals and birds, usually in the form of taxidermy. Cabinets of curiosities were the precursors of present-day curated exhibitions and museums. Starting as collections of odd fragments, they became the staples of Renaissance science. Approaching the modern era, this concept of curated collection developed enough to be applied to arts and crafts, leading to the emergence of museums and exhibitions in the present-day sense.

Les Incoherents and the Quiet Artistic Revolution

Usually, art historical texts refer to the Dada movement and Marcel Duchamp as the first artists to rely on found objects. However, the first recorded yet often ignored instance of this concept’s use refers to a little-known group of artists who shocked and provoked Parisian crowds in the 1880s. They called themselves Les Incoherents (meaning The Incoherents) and deliberately displayed works that ridiculed the art world and challenged its boundaries. They exhibited drawings by the mentally ill or untrained artists, preceding the concept of art brut, and presented monochrome canvases with titles like First Communion of Anaemic Young Girls in the Snow (a completely white painting) or Apoplectic Cardinals Harvesting Tomatoes on the Shore of the Red Sea (respectively, a bright red one).

One of the Incoherents’ experiments featured a found object, repurposed as a work of art. Writer and journalist Alphonse Allais exhibited a piece of green carriage curtain with a complex title Some Pimps, Known as Green Backs, on their Bellies in the Grass, Drinking Absinthe. Art historians believe that the short-lived activity of Les Incoherents was the starting point of conceptual art that would develop only a century later.

Around the time of Les Incoherents’ activity, found objects started to occasionally appear in the works of famous artists, although in specific contexts. The most famous example is the sculpture Little Dancer of Fourteen Years by Edgar Degas, which featured a real tutu skirt. However, this object was never entirely artistic, as it reflected Degas’ studies of physiognomy—a pseudoscience that studied the supposed correlation between a person’s facial features and criminal inclinations. He sculpted a portrait of a teenage ballerina that he believed reflected the principles of physiognomic theory. Thus, the Little Dancer was, at least partially, a scientific object, and the incorporation of non-artistic elements such as a muslin skirt provided a certain degree of realistic observation.

Found Objects and Dada

In the 20th century, manipulation with found objects became the only artistic way to match the quick-paced modern life with its technology and speed. Instead of spending months, if not years, behind a monumental canvas, modern artists could just reach for a nearby object and interpret it as an aesthetic and meaningful agent. These objects, readily available in shops, flooded everyday modern reality and constructed a separate realm of everyday interaction and consumption. Previously, the natural world was the reflection and the extension of the human one, and vice versa. In modernity, however, humans have become capable of almost complete independence from it, settling comfortably in their constructed worlds.

Initially, sound objects appeared in artworks as parts of collages and assemblages. These techniques were popular among Dada artists, who were looking for ways to reflect post-war reality in their art. Dadaist Raoul Haussman repurposed a factory-made mannequin’s head to point out the narrow-mindedness of the critical judgment of art and the inability of critics to keep up with current times.

Other modern artists who started to experiment with found objects were Cubists. Starting from collages made from newspaper clippings, they moved to sculpting objects that incorporated strings, mirrors, and other objects. Picasso’s sculpture Glass of Absinthe featured a silver sugar strainer incorporated into a painted bronze structure. For Cubists, the incorporation of real objects married their semi-abstract imagery with the material world, building a bridge between three-dimensional reality and two-dimensional painting. Later, following Cubists’ ideas, the artist of the Russian avant-garde proclaimed the principle of truth to the materials, believing that the use of familiar objects and non-artistic materials would make artworks more accessible to the wider uneducated public. Artists like Ivan Puni incorporated builder’s instruments like saws and hammers into their compositions as acts of solidarity with the working class.

Marcel Duchamp: The Father of Conceptual Art

Marcel Duchamp was one of the few artists of his time who did not brush off the nonsensical experiments of The Incoherents. Although Duchamp was born during the movement’s final days, his artistic practice relied on careful research and thorough work with references. In the mid-1910s, Duchamp came up with the idea of readymades—objects that had little to no involvement from the artist’s side. Thus, he proclaimed that the act of choosing an object as an expressive artistic statement was much more important than the artistic skill and originality involved in crafting it from scratch.

In 1913, Duchamp attached a bicycle wheel to a stool and presented this construction under the title Bicycle Wheel. According to Duchamp, he did not have a specific meaning in mind. He just enjoyed the structure’s form and appearance. According to some art historians, the Bicycle Wheel was one of the first examples of kinetic art that typically involves moving mechanisms. However, Duchamp’s most famous found object was the scandalous Fountain, an overturned urinal allegedly sent to him as a sculpture by another Dada pioneer, Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven.

Some Dadaist experiments with found objects involved manipulating the object’s initial purpose. The sculpture Gift by Duchamp’s close friend and collaborator Man Ray represented an iron covered with nails. From a rather dangerous yet useful household item, the iron transformed into a menacing hybrid that was good only for violence.

Conceptual Art and Found Objects

Propelled by Duchamp and the Dadaists, manipulation with found objects moved to other artistic movements. The Surrealists injected familiar objects with extra meanings, making them symbols of repressed desires and dark dreams. Pop artists used goods and their packages to reconstruct the modern reality around them.

By the 1960s, the concept of appropriating pre-made materials and objects developed into the idea of conceptual art. Like Marcel Duchamp, conceptual artists valued artistic ideas over their material representation. Artists were not obliged to craft their creations anymore; instead, they were expected to rethink their relationship with reality through existing material means. The capitalist abundance of mass-produced and readily available objects transformed our relationship with them.

As the general population started to value their belongings less, either preferring or being directly forced to buy cheap disposable goods, the language of art and its perception transformed similarly. Instead of relying on materials and skills, artists and collectors started to value something immaterial, impossible to reproduce and sell—a creative idea and unique perspective.

In tune with the ideas of early Soviet avant-garde sculptors, found everyday objects often built more inclusive contexts around their use in art. Due to their widespread use, these objects act as universal symbols, more accessible and relatable to the larger public than traditional symbolic systems used in pre-modern art.