Francisco Goya is an artist of late 18th-century and early 19th-century Spain who suffered terribly during his life. He had a wonderful early life with a wildly successful career as a court artist, yet once his life was touched by illness and war, he began to see the world through a more pessimistic lens. Goya’s criticisms of the world around him were recorded in his artworks, with one of the most important insights into his opinion of society being Los Caprichos, a set of 80 prints criticizing Spanish society.

Who Is Francisco Goya?

The famous Francisco Goya was born in 1746 in Fuendetodos and was educated in Zaragoza by Escolapian Fathers at a monastic school. There, he was encouraged to always think critically and to be responsible in acquiring knowledge throughout life. This upbringing allowed him to become a painter, though he did have a background that could help with networking. He had a family working in art, including his father. His father was a gilder working on projects for the construction of a new large church in Spain. The connections from his past secured him a job in Jose Luzan Martinez’s studio.

After spending time working with Martinez, Goya moved to Madrid and took up a new position under Francisco Bayeu in order to save up for a trip to Rome. Rome was considered one of the best places for budding artists to hone their talents and learn techniques by observing classical art and masterworks of other artists. During Goya’s time with Bayeu, he worked as a cartoonist for tapestry designs. Unlike the artwork Goya is most well-known for, the cartoons of his early career look back to the Rococo era and are colorful, bright, and whimsical. They often featured young, beautiful aristocrats traipsing blissfully through the countryside.

When Goya returned from Rome to continue his career in Spain, he was brought to court and made an official painter to the King of Spain in 1789. It became fashionable to have portraits made by Goya in his expressionistic style that some criticized as ugly. Some argue that Goya making the royal family look ugly in their portrait was a political comment on his opinion of the monarchy. No matter his reason, he was well-liked as a court painter and was living a successful life.

While working at the court, Goya became part of a group of progressive thinkers who hoped to see social and political progress in Spain. They were enlightened thinkers who placed value on reason, education, nature, humanities, and science. These values would later cause problems for him at the Royal court.

In 1792, Francisco Goya fell ill and permanently lost his hearing. This was a major turning point in his life, which is evident in the shift in his artwork. His work changed to a more severe outlook on life. The exact illness that Goya suffered from is still unknown, though some historians suggest it could have been lead poisoning that caused the severe illness. Goya’s loss of hearing was a massive blow, and he retreated into privacy for a few years, taking a break from commissions and experimenting with new expressionistic styles and subjects. At the end of the 1790s, he returned to his work with a much darker, moodier style.

Works that he created at the end of the 18th century include the witchcraft series that he painted for the Duchess of Osuna (known for her scandalous behavior and strong personality), Lunatics in the Courtyard, and Los Caprichos, all of which were visual criticisms of what Goya deemed societal follies. Themes include religion, superstition, ignorance, morality, vanity, love, and marriage.

Goya’s popularity rose at court during the reign of Charles IV of Spain. However, the King would be overthrown by the French when Napoleonic troops took Barcelona and Pamplona and subsequently forced the Spanish King to abdicate the throne in 1808. Napoleon’s brother, Joseph Bonaparte, was placed on the throne, much to the dismay of the Spanish. Goya likely would have initially been at least somewhat satisfied with this outcome due to his progressive values and the belief that France could carry Spain into the future with their enlightened ideals. Goya would be disappointed when, in an attempt to show his power, the new King ordered mass executions against anyone who had rebelled against his rule. Despite this, his rule was short-lived anyway. War continued to ravage Spain, and eventually, Napoleon was defeated in 1814.

Francisco had a good life with a successful career where he was able to develop progressive ideals with hope for the future, all of which turned sour after a severe bout of illness that left him permanently deaf, as well as witnessing the horrors of occupation, rebellion, and war. Goya began to realize the problems with the society he lived in and attempted to be vocal about these criticisms through his artwork. Today, his artwork is known as some of the darkest art throughout the history of Western art, and it stems directly from his tragic backstory and ability to see society through a pessimistic lens in order to shed light on the follies of society in hopes that the situation might one day improve.

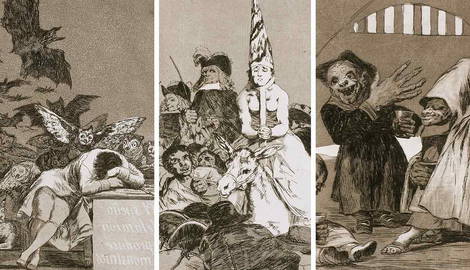

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

In the first print of the Los Caprichos set, Goya represents himself with a scathing expression and a top hat to signal to viewers of the set that the following scenes are visual interpretations of his criticisms and complaints about society. He peers at the audience through the corner of his eye. He is watching and judging displeased with the world around him.

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters is number forty-three in the series of prints. In this etching, a man sits at his desk. It is littered with writing utensils and paper, yet the man at the desk does not interact with them. Instead, he tucks his face into the crook of his arm and sleeps. Behind him, his dreams erupt into various creatures such as bats, owls, and cats. The inscription on the side of the desk reads, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” Possibly, Goya is attempting to communicate that society could be improved if people opened their eyes and observed the state of things, yet they prefer to sleep.

As a result, the monsters grow stronger as they are ignored to reduce discomfort, ultimately making it worse for everyone. Francis D. Klingender, a German art historian from the first half of the 19th century, believes that this print is meant to represent the progress that could occur in Spanish society. He writes, “Passion guided by reason inspired the finest deeds of the Spanish people. But abandoned by reason, faith, selfless devotion, loyalty, heroism, the search for truth, and the passionate love of freedom are turned into evil negations: superstition, bigotry, selfishness, base-flattery, cowardice, heresy-hunting, and servility.”

Hunting for Teeth

Hunting for Teeth is number twelve in the series of prints. It features a young woman standing on top of a brick wall to reach a hanging man. She reaches her hand out and places her fingers in her mouth in order to grab the teeth from the dead man. She shields her face with a handkerchief, clearly aware of the bad morals behind the situation. In this print, Goya points out that people will do horrible things for their own gain, throwing their morals away in exchange for money. However, Goya would have been aware of poverty, another societal issue. Therefore, this print may have a double meaning in that desperation is rampant in an uncaring society, which leads to desperate and immoral acts out of necessity.

How They Pluck Her!

How They Pluck Her! is number twenty-one in the series of prints. In this print, Goya depicts the men as predators. He gives them cats’ faces and whiskers to symbolize this. The bird that the three men have caught is a symbol of prostitution. They are plucking her feathers, taking from her.

There Was No Help

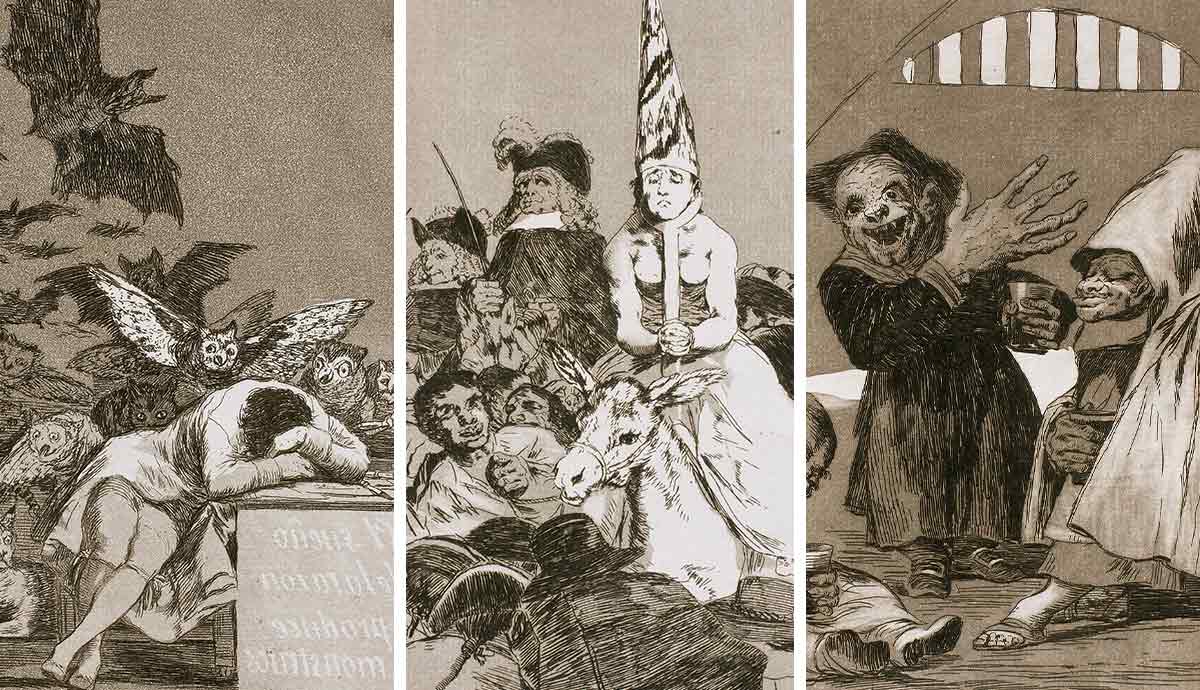

There Was No Help is number twenty-four in the series of prints. Spanish people were still incredibly superstitious in the late 18th century and early 19th century, which Goya found detrimental to societal progress. One of his biggest complaints was the effects of the Spanish Inquisition. Those accused by the Spanish Inquisition would be paraded around on a donkey, wearing a dunce cap, while crowds would gather in droves to watch alleged witches being publicly shamed. That is the situation Goya chose to depict here. The title of the print shows a sympathetic view on Goya’s part, and the print serves as a condemnation of the Spanish Inquisition and its supporters.

Might the Pupil Not Know More

Might the Pupil Not Know More? is number thirty-seven in the series of prints. This print shows two donkeys. One is young, learning to read its ABCs. The title suggests that the young donkey is not receiving a satisfying education. The teacher, just as much an ass as the student, is teaching content that they do not know. Goya understood that if Spain wanted to make cultural progress compared to the other countries in Europe, they would need to place more value on equal opportunities concerning education for everyone in the country and that the first thing to do was to provide qualified teachers for students.

The Spanish monarchy was reverted back to the royal family Goya had served before the invasion and war, though the King was now Ferdinand VII. Ferdinand VII was not as progressive as his father, which would become a problem for Goya. He stopped receiving royal commissions at court, and all those who initially supported the French, including Goya, were questioned by authorities. However, he seems to have escaped too much scrutiny as he was commissioned to create paintings commemorating the brave rebels that stood up to the French occupiers, titled The Second of May, 1808, and The Third of May, 1808. The Third of May, 1808, especially, shows how the horrors of war affected Goya, with the terror of the central subject’s expression being notoriously jarring to viewers.

Francisco Goya’s Hobgoblins

Hobgoblins is number forty-nine in the series of prints. This print shows three hobgoblins dressed in the robes of monks or clergymen. They have long, grotesque fingers and sharp, pointed teeth. Contemporaries of Goya wrote about this print, claiming the large hands were meant to symbolize the greed of the Catholic Church. Goya shows the clergymen as little monsters, feeding off of society’s goodness, labor, and money. Goya wrote in explanation, “These are the other people. Cheerful, playful, helpful, and a little sweet, friends that will serve you a trick, but very good little men.”

However, the Catholic Church held considerable power in Spain at the time, especially considering the Spanish Inquisition. Many people were religious and superstitious, a dangerous mix that would ignite if given a reason. Therefore, many art historians believe this would have been his backup excuse if asked about the image by religious authorities. He certainly would not have been able to be so openly against the church, leaving the meaning behind this print open for interpretation.