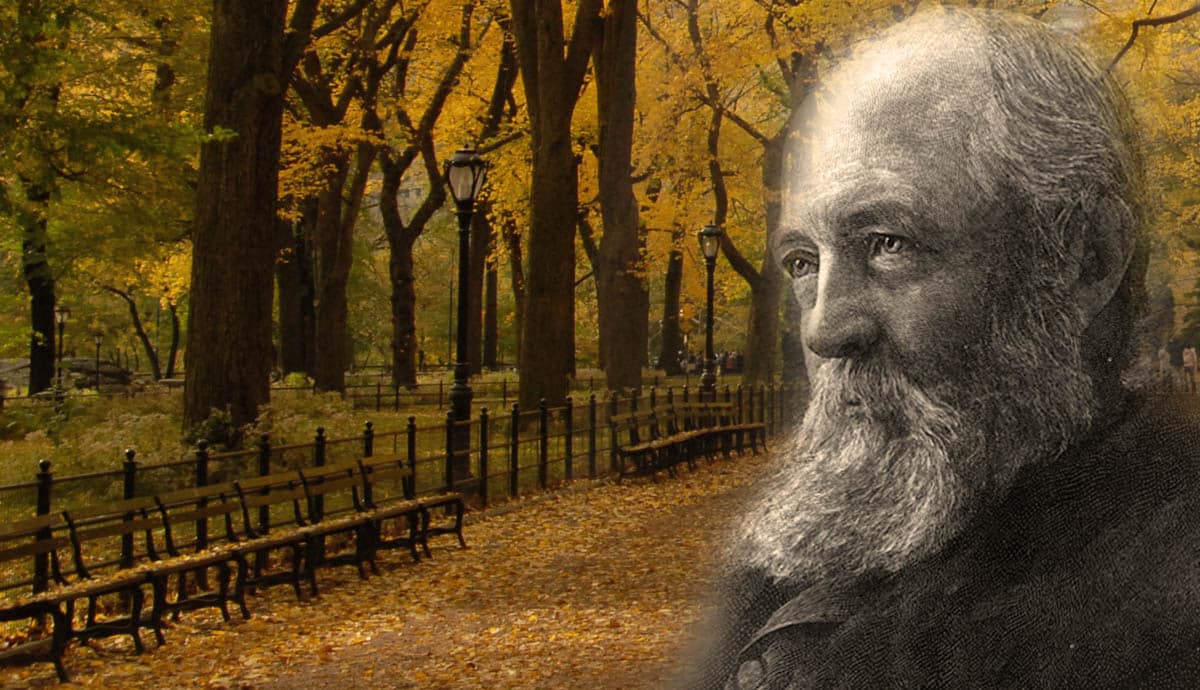

Frederick Law Olmsted was probably the most important American landscape architect of all time. Despite not taking up the profession until well into adult life, Olmsted had a monumental impact on the field. His countless achievements include Central Park, Prospect Park, Biltmore Estate, the Emerald Necklace parks, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, the Stanford University campus, and the U.S. Capitol grounds. His philosophies about the importance of green space to physical, mental, and community well-being are at least as significant as his realized projects. The year 2022 is the two-hundredth anniversary of Olmsted’s birth, and parks advocates around the country are raising awareness of his incredible legacy.

Frederick Law Olmsted – Early Years

Frederick Law Olmsted got his interest in the landscape from his father, who loved the outdoors and took his son on nature excursions in New England starting at an early age. The young Olmsted began to develop strong ideas about scenery, which would later inform his landscape architecture. He would not, however, consider entering the profession for another few decades. In the meantime, he bounced around between diverse careers, including sailor, farmer, and journalist. He traveled to China and Panama and also made several trips to Europe in his adult life. Before the American Civil War, he traveled throughout the south, reporting on life in the slave states for the New-York Daily Times (today’s New York Times). During the Civil War, he ran the United States Sanitary Commission, a precursor to the American Red Cross, before spending two years managing a failing gold mine in California.

Olmsted was certainly a Renaissance man, but he also seems to have been a bit lost in his early adulthood, as he bounced from occupation to occupation. Even in his more focused later years, he frequently suffered from mental health complaints and also often struggled to get along with his clients and collaborators. Despite this, Olmsted’s varied experiences gave him many of the skills he needed to become such a great American landscape architect, particularly his effective organizational and administrative skills. Olmsted did not have much of a formal education, but he read widely.

Central Park

In 1857, Olmsted’s ever-wandering career led him to become Superintendent of Central Park, at that time an empty parcel of unappealing land. After decades of talk, New York City had finally gotten serious about developing a large, public park for the benefit of its inhabitants. However, fate had something more in store for Olmsted than simply overseeing the park’s construction. When park commissioners announced a competition for the park’s design later that year, British-American architect and landscape designer Calvert Vaux (1828-1895) asked Olmsted to collaborate with him on what would be the winning proposal.

Although Vaux was the more experienced of the two, Olmsted was a visionary, and his reputation would soon eclipse Vaux’s. Nevertheless, Olmsted always credited Vaux as the person who made him a landscape architect. It would, however, take a few more years and diverse endeavors before Olmsted truly took up that title. After his Civil War work and unsuccessful experience in gold mining, he returned to New York City and officially formed a partnership with Vaux in 1865. They worked together for seven years on Central Park and other projects, such as Prospect Park in Brooklyn and the parks system in Buffalo, New York. Olmsted and Vaux dissolved their formal partnership in 1872, each striking out on his own. However, they later collaborated on the park on the American side of Niagara Falls.

Frederick Law Olmsted – Landscape Architect

Landscape architecture was a very new field when Olmsted entered it. In fact, he and Vaux were the first Americans to ever use that title. However, the American landscape architect was much more than that; he was also a master organizer, social reformer, city planner, and environmental advocate. Every time he designed a landscape, he did so in service of bigger ideals. From his childhood, he understood the benefits of spending time in nature. As an adult, he dedicated much of his career to making those benefits accessible to as many people as possible, particularly city-dwellers.

Olmsted worked based on the principle that access to green spaces has a powerful effect on human physical and mental health, and also cultivates healthy community relationships. Olmsted was democratic in these principles, believing that parks should be available to all and could serve as places for all members of society to interact productively, including different social classes that wouldn’t usually mix otherwise. He coined the term “communitiveness” to express this idea of diverse people coming together through the landscape. In many ways, his true significance lies as much in the philosophy behind his work as it does in the work itself.

Although Olmsted was born two hundred years ago, his ideas about the environment and its role in human well-being sound surprisingly modern. In a time when American industry, wealth, and culture were largely built through extremely detrimental labor and environmental practices, Olmsted believed in the necessity of supporting the natural environment and making it accessible to everybody in the name of improved physical and mental health for all.

Preservationist and City Planner

Following the 19th-century American nature preservation movement, and based on his experiences out west, Olmsted became keenly interested in preserving the natural environment. He was an early advocate for the government to preserve Yosemite, which he had visited, as a resource for all. His son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., was closely involved in the National Park Service when it first opened in 1916. Olmsted Sr. also advocated for preserving and protecting Niagara Falls when it was becoming a victim of its own tourist appeal in the 1880s. He and Vaux worked together on the new park created there to simultaneously protect the falls and make them accessible to all.

Olmsted sparked what was to become a major effort in American forestry at Biltmore, revitalizing the native forest that was already severely denuded when George Washington Vanderbilt bought the property. One of the reasons that the American landscape architect was so keen on parks, besides their benefits to the populace, was the fact that they could protect landscape scenery from destructive commercial interests.

The American landscape architect seems to have possessed a special gift for transforming and revitalizing the most abused and despondent land. Many of his most celebrated projects, including Central Park and Boston’s Back Bay Fens, came to life on formerly barren, swampy, and unappealing sites. In his work on campuses like Stanford University, suburbs like Riverside, Illinois, the U.S. Capitol Grounds, and the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Olmsted acted as much as a city planner as he did a landscape architect. His treatment of roads, in particular, played heavily into Olmsted’s success.

The idea of sinking four cross-park roads into ditches to preserve Central Park’s vistas helped Olmsted and Vaux win that project, while the winding, three-mile approach road at Biltmore House is considered one of the estate’s most spectacular features. He had ideas about how to structure the Stanford University campus to create the best student experience, and how to orient the buildings in asylums to give patients the most sunlight in their rooms. American landscape architecture was always a vehicle for social improvement for Olmsted.

The American Landscape Architect’s Aesthetic

Frederick Law Olmsted had no patience for artificial-looking, formal, heavily manicured landscapes fashionable in Europe at this time. Although he occasionally did create more structured settings, like The Mall in Central Park or the landscaping directly surrounding Biltmore House, he preferred an unstudied, rural effect. The American landscape architect’s creations tend to be soft, varied, and slightly wild.

Believing that nature has its strongest and most positive impact subconsciously, he was not a fan of obviously-artificial elements and dramatic showpieces, such as flower beds and exotic plants chosen to impress. He didn’t restrict himself to native plants, but he only used varieties that would grow well in the local climate and fit into the area without drawing undue attention or maintenance. He also valued coherency and interconnectedness, blending different kinds of scenery into a cohesive whole so that people could appreciate the overall effect, not individual plantings. Olmsted’s landscapes are about the whole, not the parts, and he carefully designed visitors’ sightlines and experiences as they moved through his outdoor creations.

The American landscape architect began to develop his theories about the landscape long before he began work on Central Park. During his first visit to England, Olmsted was quite struck by the English countryside, which would exert a strong influence over Olmsted’s landscape aesthetics. So, too, did the landscape-related writings of Englishmen William Gilpin and Uvedale Price about the Picturesque. Halfway between the broad, wide-open pastoral landscape and the awe-inspiring Sublime, Picturesque refers to an essentially gentle natural environment with some wild elements. Olmsted utilized both Picturesque and pastoral aesthetics in his projects.

He liked the idea of stretching green spaces as far as he could, connecting various areas of nature as much as possible. In fact, he invented the now-familiar concept of a parkway (a road integrated into green space) to connect his parks in Buffalo, New York. He was very sensitive to the specifics of each site and climate. For example, he turned down a request to create a second Central Park in San Francisco, because that design did not fit Southern California’s hot and dry climate. He aimed to work with a site’s natural topography when possible, but he was also capable of great artifice when necessary.

Many of his parks include very natural-seeming lakes, meadows, and forests that were completely man-made, but he intervened no more than was necessary and always did so with a site’s existing elements in mind. Similarly, every Frederick Law Olmsted project differs according to the unique needs of the situation. In urban parks, for example, the landscape is meant to overshadow everything else, but at the U.S. Capitol, both landscape and hardscape were designed to support the building and what goes on inside.

Frederick Law Olmsted long resisted considering himself an artist. Yet his writings show that he thought about his landscapes in much the same way a landscape painter would, employing a variety of textures, tones, and effects of light and shade to create a composition. His desire to blur edges and blend one type of scenery into the next sounds a lot like a painting made with soft and loose brushwork. Daniel Burnham, director of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition, once called Olmsted “an artist, he paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountain sides and ocean views.”

Despite Olmsted’s lasting influence and acclaim, not all the projects commonly associated with his name were done completely to his specifications. Landscapes are labor-intensive, expensive, and ever-changing endeavors, and Olmsted usually delegated the day-to-day construction concerns to subordinates. Once he submitted his designs to his clients, he had no guarantees that things would progress exactly as he wished. Clients often changed their minds later, refused to approve Olmsted’s most unusual ideas from the start, or modified away from his designs at a later date. Some of the most visionary aspects of his designs, like those for Mount Royal Park in Montreal, were never completed as intended. In many cases, Olmsted’s name is associated with a project because he consulted on it and proposed designs for it, not necessarily because the actual landscape we know today is completely Olmsted’s vision.

Frederick Law Olmsted’s Legacy

Frederick Law Olmsted retired from landscape architecture in 1895. Biltmore Estate was his last project. He spent the last few years of his life in an asylum whose grounds he had designed. Olmsted’s son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (1870-1957), and stepson, John Charles Olmsted (1852-1920), took over the business, and his daughter, Marion, was involved as well. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. proved to be as talented as his father, and the firm remained highly prolific and influential throughout the 20th century.

Meanwhile, Olmsted’s parks, campuses, and other green spaces continue to be enjoyed, valued, and celebrated by their local communities. April 26, 2022 is Frederick Law Olmsted’s 200th birthday, and it comes at a time when many Americans have come to appreciate public outdoor resources more than ever before. The National Association for Olmsted Parks is coordinating a year’s worth of events to raise awareness of Olmsted’s incredible legacy and its resonance for us today.