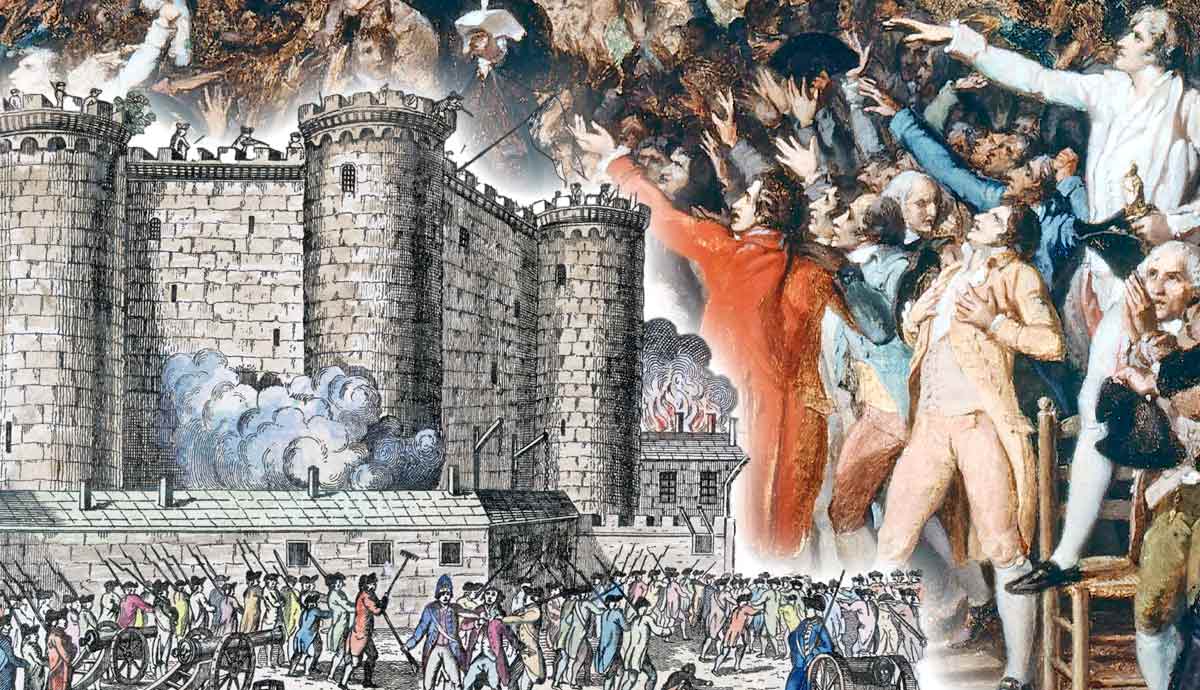

The French Revolution is one of the most well-known events in European history. Starting in July 1789 with the Storming of the Bastille, the violence soon escalated into a bloody reign of terror. Thousands lost their heads to the guillotine, including King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette. But it’s far too easy to focus on the violent nature of this event and neglect the underlying causes of the French Revolution. Indeed, there were multiple factors that led to the violent revolution, ranging from philosophical ideas to unfair taxes and an unpopular view of the monarchy. Below are six of the principal causes that led to the French Revolution.

1. The Third Estate Taxation Burden

Before the revolution, French society was divided into three estates, simply known as the First Estate (clergy), the Second Estate (nobility), and the Third Estate (commoners).

These estates were not taxed equally. While the Catholic clergy (the First Estate) and the nobility (the Second Estate) paid very little tax, everybody else (the Third Estate) had to pay a form of taxation known as the taille. This royal tax was one of the most hated aspects of pre-revolutionary France.

Despite being a small percentage of the French population, the Catholic clergy owned ten percent of the land, and the nobility owned a quarter. Though some peasants did own the land they worked on, they were the exception, not the rule. The vast majority of peasants had to pay feudal obligations to their landlords and received poor wages for their work.

A series of poor harvests in the 1770s and 1780s exacerbated the plight of the peasantry. These unfortunate weather events raised food prices, leading to an increased level of poverty throughout the country. In 1788 – just one year before the start of the French Revolution – the crop yield was particularly poor.

Worse still, the political system was rigid and hierarchical, preventing poorer individuals from ascending the social ladder by blocking them from positions of power. Positions in the royal bureaucracy, for instance, were reserved for members of the nobility.

However, though it’s important to recognize the importance of the three-estate system when discussing the causes of the French Revolution, it should be stressed that there were significant differences within the estates.

Bishops and abbots who belonged to the First Estate had much more wealth than the nuns who worked in orphanages, and country nobles did not have the same wealth as the court nobles. There was also a big difference between educated professionals (such as lawyers) and the non-landowning peasantry, even though both groups belonged to the Third Estate.

2. Anglo-French Rivalry and Expensive Wars

Britain and France were colonial rivals throughout the 18th century, fighting for overseas territory in pursuit of economic prosperity and global influence.

The French suffered significant losses during the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763). The British destroyed fleets in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, acquiring many French colonies in the process. The French also lost their influence in Canada following the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

Hungry for revenge, the French joined the Americans during the Revolutionary War (1775–1783). France’s involvement in this conflict was crucial. By declaring war on their overseas rival, the French stretched the capacity of the British navy, claiming victory after the Battle of Cuddalore in 1783.

But despite their success, victory came at a cost to the French economy. In addition to the loans and supplies, the French spent lots of money moving their troops over to support the American Revolution. Taxes had to be raised to pay for these costs, and – given the unfair tax system – it was the Third Estate who were hit hardest by France’s involvement in the conflict.

The French also spent plenty of money on their army alongside their navy because of their land borders with other European powers. Conversely, the British – who lived on an island surrounded by water – could protect themselves at home and abroad just by having a navy.

3. Industrialization & Consumerism

Though most of France’s poorer population resided in the countryside, plenty of people still lived in urban areas.

France’s levels of industrialization were similar to Britain’s during the 18th century. Roads and canals accelerated travel and trade, while the overseas colonies brought in resources and products from abroad. Soon, there was a high demand for items like watches, dresses, and furniture, and such items became less exclusive as time went on.

However, some aspects of commercialism amplified the inequalities that already existed in France. Sugar and coffee from overseas colonies, muslins from India, carpets from Persia, and porcelain from China stood alongside French-made products like silk stockings and hardwood desks.

Many of these items were only available to the wealthier members of society. This put the plight of the poor into sharp relief, casting a light on the inequalities of urban society and creating feelings of bitterness.

4. Royal Resentment & Marie Antoinette

While the French did have a government in the 18th century, royal authority was considered absolute, meaning there was no institution or constitution that could prevent him from doing what he wanted.

Kings throughout French history believed they had a divine right to rule the people as God’s representative, suggesting the monarch was morally superior to his subjects. This holier-than-thou attitude alienated the French population.

Furthermore, the mighty Palace of Versailles, which had been built during the reign of King Louis XIV, symbolized the luxury of the royal court. With its beautiful apartments, chambers, and gardens, the palace seemed like a separate world when compared with the day-to-day work of peasants in the countryside or the industrial workers in the cities.

Marie Antoinette, the wife of King Louis XVI, also fostered resentment amongst the French public. Married off to the future King of France when she was just 14 years old, Marie Antoinette enjoyed expensive fashion, art, and entertainment.

She had little consideration for the money she spent and gambled away fortunes playing billiards and cards. The French press picked up on their queen’s liberal spending habits and gave her a cruel nickname: Madame Deficit.

5. The Enlightenment Philosophers

It wasn’t just the press who criticized the French monarchy. Throughout the 18th century, a group of philosophers wrote about the issues they saw in society. The work of these philosophers and the political ideas they promoted were referred to as the Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment was a pan-European movement, but many of the most well-known Enlightenment philosophers were French. In The Social Contract (1762), Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously wrote, “Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains,” arguing that the average man should have more political influence.

Other French philosophers like Voltaire and Montesquieu also added their voices to the Enlightenment movement, highlighting the importance of reason and human progress. They disliked the Catholic Church as an institution, criticizing the irrational, superstitious attitude of Catholic clerics and the idleness of unproductive monks.

In 1751, a collective philosophical work simply called Encyclopédie was published for the first time. The Enlightenment philosophers continued to contribute their works in fresh installments of Encyclopédie for several years.

Thanks to the work of clerical teachers during the 18th century, the proportion of people in France who could read and write jumped from a fifth to a third. This dramatic increase in literacy rates helped to spread Enlightenment ideas like those discussed in Encyclopédie.

6. Revolutionary Culture

The work of the French philosophers and the increasing literacy rates were part of a broader cultural shift, especially in urban areas with high-density populations, such as Paris.

In the decades prior to the revolution, public lectures, scientific clubs, provincial academics, and freemason societies increased in volume, expanding France’s intellectual sphere. This promoted critical thinking skills and anti-establishment views among the urban population.

Theatrical performances also promoted revolutionary ideas. Perhaps the most obvious example is The Marriage of Figaro by Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais. In this play, a servant called Figaro tries to one-up his master and raises concerns about the inequalities in France.

The play was considered radical at the time and was initially banned from the public, forcing actors to perform it in secret. Royal censors then decided to lift the ban, and in 1784, it was performed at one of the biggest theaters in Paris. Before long, The Marriage of Figaro was one of the most popular plays in the country.

The Causes of the French Revolution: The Historiographical Debate

The causes of the French Revolution have been debated for many decades, with different groups of historians prioritizing certain causes over others.

Marxist historians, for example, saw the revolution through the lens of class struggle, contrasting the plight of the Third Estate with the privileges of the First Estate and the Second Estate. Though this viewpoint shouldn’t be discarded entirely, it does oversimplify the causes of the revolution.

Indeed, revisionist historians pushed back against the Marxist interpretation, looking for alternative explanations. They emphasized the cultural changes that occurred during the eighteenth century, arguing they helped to foster a revolutionary fervor among the French people.

Of course, both sides of the argument carry merit, with all of the aforementioned causes contributing to the outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789. When it comes to picking the most important factor, there’s no objectively correct answer, and this topic will continue to divide historians for many years to come.

A Culmination of Causes

While tensions were building up gradually over time, the French Revolution officially began on June 20, 1789 when the Estates General, France’s parliament, collapsed when members of the Third Estate – representing the common people – formed their own National Assembly and began to campaign for constitutional reform. This political crisis led to a wave of revolutionary hysteria and the storming of the Bastille as a symbol of the royal family and its authority on July 17, 1789.

After a long period of debate over a new constitution and political reforms, the king was arrested in 1792. Later that year, on September 22, the National Convention was established and the monarchy officially abolished in favor of the French Republic. The king was tried and executed as a traitor on January 21, 1793, and his wife Marie Antoinette months later on October 16. Following this execution, the new French government went to war with various European powers and infighting broke out within the National Convention. This opened the way for the radical Montagnards to take power and start a year-long “reign of terror,” killing thousands of their enemies.

In 1795, power was taken by a new regime called the Directory with the assistance of the army led by the young general Napoleon Bonaparte. He led a series of successful wars. Belgium was annexed, the Dutch Republic surrendered, and peace was made with the Prussians and Spanish.

Despite these military successes, there was general dissatisfaction with the leadership of the Directory. On 9 November 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte staged a coup d’état, abolishing the Directory and appointing himself France’s “first consul.” This marks the end of the French Revolution and the start of the Napoleonic era.