The Erinyes, also known as the Furies, were goddesses of vengeance and retribution in Greco-Roman mythology. They were responsible for punishing individuals who committed serious offenses in society, such as murder—especially the killing of family members—acts of impiety, perjury, and violations of hospitality laws. The Erinyes relentlessly pursued their targets until they were either cleansed of their sins or driven to madness. These feared winged goddesses, draped in darkness and coiled serpents, personified one’s hatred and desire for revenge. Discover more about the Erinyes, the agents of justice and retribution.

The Origins of the Furies (Erinyes)

The term “Erinyes” has ancient roots dating to the Mycenaean period. Scholars continue to debate its precise meaning, with interpretations including “strife,” “to move or stir,” “to hunt or persecute,” and “one who provokes struggle.” In ancient Rome, they were known as the “Dirae” (the ominous ones) or the “Furiae” (the frenzied ones), which is where the term “Furies” comes from.

Like many mythical figures, there are various stories about their birth. As the embodiment of intense vengeance, it is unsurprising that the Furies are ancient deities born long before the Olympian gods. One of the most famous tales of the birth of the Erinyes, as described in Hesiod’s Theogony, revolves around a violent act that encapsulates much of what the Erinyes were known to represent and punish.

The Furies were born from the spilled blood of the primordial god Uranus, the personification of the sky, after his son, the Titan Cronos, castrated him. The Erinyes, along with the Giants and Meliae tree nymphs, emerged when droplets of Uranus’s blood fell onto Gaia, the personification of the earth. Interestingly, Aphrodite, the goddess of love, was also born during this brutal act when Cronos cast his father’s genitals into the ocean.

The castration of Uranus was a vicious act of familial violence—an offense the Furies take very seriously—and also served as a means of vengeance and punishment. Cronos was urged by his mother, Gaia, to overthrow his father. Uranus was a cruel and unforgiving ruler who imprisoned all his children in the depths of Tartarus due to his paranoid fear that one of them would attempt to usurp him and take his power. In her desire to free herself and her children, Gaia entrusted her son Cronos with enacting vengeance against Uranus. The birth of the Erinyes symbolizes the conflicting elements they came to embody: the desire for vengeance and the taboo associated with shedding the blood of family.

While alternative origin stories may lack the same sense of familial conflict and vengeance, they share a sense of fear, dread, and death often associated with the Furies. In other accounts, such as Aeschylus’s play, Eumenides, and Ovid’s Metamorphoses, the Erinyes are depicted as the daughters of the primordial goddess Nyx, the personification of night. The Furies are Chthonic deities closely linked to the Underworld. This strong connection with the realm of the dead has led many to believe that they are the daughters of Hades.

In the Roman epic Aeneid by Virgil, the Furies are portrayed as the daughters of Nyx and Hades. In contrast, the Orphic Hymns state that the Erinyes are the offspring of Hades and Persephone, the king and queen of the Underworld. However, in the Thebaid by Statius, it is suggested that Hades is the sole parent of the Erinyes.

Wrath of the Erinyes: What Was Their Function?

The primary purpose of the Erinyes was to punish the guilty and avenge crimes such as impiety, mistreatment of supplicants, violations of hospitality, perjury, disobedience to parents, disrespect toward elders, and, most importantly, murder and blood guilt. Those targeted by the Erinyes were driven to madness, losing their grip on reason and occasionally becoming blind. The Furies were associated with avenging blood guilt for crimes against family, particularly the murder of parents and elderly relatives.

In ancient Greek society, certain acts of homicide, especially the killing of family members, were considered so heinous that they polluted the soul of the perpetrator. These acts were referred to as “blood guilt,” and the only way to cleanse this guilt was through ritual purification performed by an anointed king or priest. If the offender failed to atone and gain ritual purification, the Erinyes would pursue them, gradually driving them to madness before dragging them down to the Underworld.

The Erinyes did not distinguish between accidental and intentional killings. In Greek mythology, there are several cases where individuals accidentally kill family members and must seek purification before the Furies find and punish them.

The Erinyes were viewed as the embodiment of curses placed upon the guilty. They served as a means for the bereaved and those seeking justice to express their desire for punishment, whether motivated by justice or revenge. One of the most lethal curses associated with the Furies is a parent’s curse upon their child. When such a curse was invoked, it stripped the victims of their peace of mind and happiness and prevented them from having children.

The Furies had functions beyond their relentless pursuit of vengeance. When not pursuing the guilty in the land of the living, the Erinyes resided in the Underworld, where they oversaw several duties. They assisted newly deceased souls in purifying their sins before transitioning to the afterlife. However, the souls of those who committed heinous crimes could never be purified and were instead sent to the dungeons of the damned in Tartarus. The Furies served as the jailers of the dungeon, overseeing the damned souls and administering their punishment through unimaginable torture.

As deities responsible for punishing the living and the dead, the Erinyes were thought to have some influence over fate, however, their control differed from that of Zeus and the Moirai, the three sisters of fate. The Furies specifically oversaw the fate of individuals destined for a life filled with misfortune and suffering. Additionally, one of their roles as goddesses of fate was to prevent humanity from gaining too much knowledge about the future.

The Erinyes were known to instill fear and respect among the ancient Greeks, and invoking their name when taking important oaths was common. For instance, in the Iliad, Agamemnon calls upon the Furies, saying, “The Erinyes, that under the earth take vengeance on men, whosoever has sworn a false oath.” Swearing by the Erinyes highlighted the importance and truth of any oath. Anyone who lied or broke an oath sworn in the name of the Erinyes risked attracting their attention and facing possible wrath for invoking their name in vain.

Who Were They, and What Did They Look Like?

Early accounts do not provide precise names or a specific number of the Erinyes. Still, over time, sources commonly identified three Furies: Tisiphone (the avenger of murder), Alecto (the implacable or unceasing anger), and Megaera (the envious one). All were feared for their power, and invoking their names was taken very seriously. To lessen the fear of invoking the Furies and attracting their attention, the ancient Greeks developed a series of euphemistic titles for these goddesses of vengeance.

The most popular title given to the Erinyes is “Eumenides,” which translates to “the well-meaning ones” or “the kindly ones.” This title was first used after the infamous trial of Orestes, one of the most well-known figures pursued by the Erinyes. Another euphemistic title for the Furies in Athens was “Semnae,” which means “the august ones” or “venerable goddesses.”

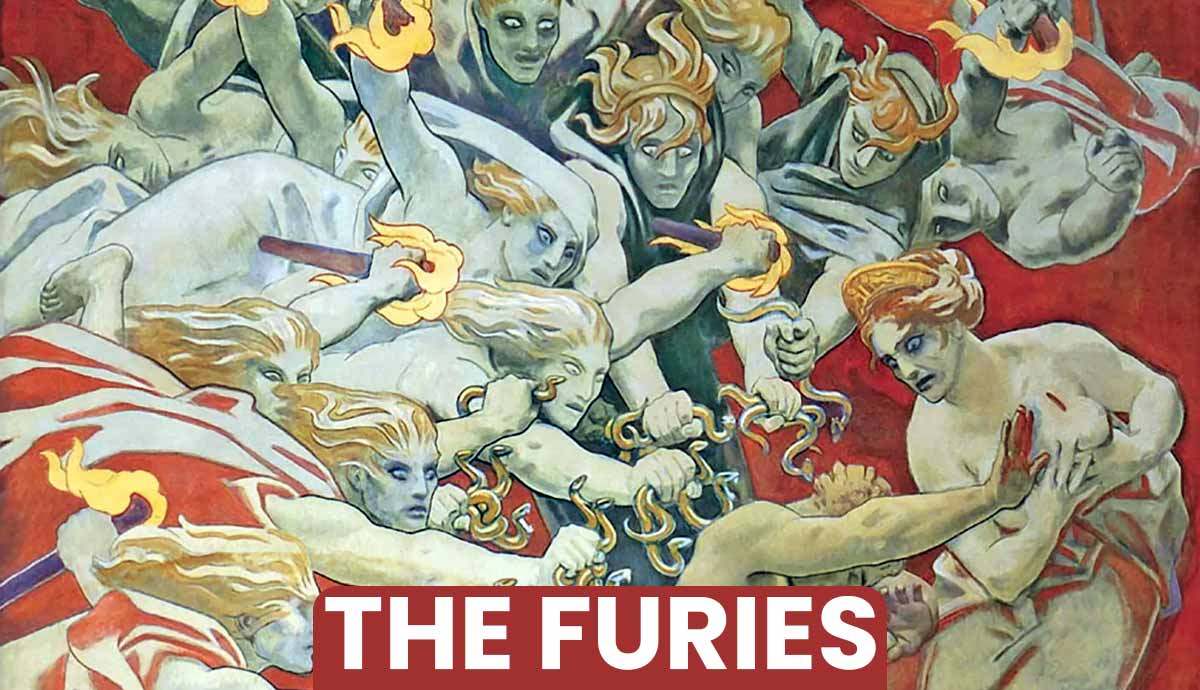

Descriptions of the Erinyes reflect their feared and terrifying reputations. The playwright Aeschylus depicted them as resembling the monstrous Gorgons, with serpents coiled in their hair and arms, draped in black garments, and blood continuously streaming from their eyes. Other writers, including Euripides, frequently described them as having wings. As huntresses of the damned, the Furies were often portrayed wearing a short chiton—a type of tunic worn in ancient Greece—along with hunting gear, distinctive hunting boots, and carrying torches and whips. Over time, the depiction of the Erinyes became more subdued, transforming them into solemn virgin maidens of the grave. They were often shown wearing hunting gear and adorned with a crown of snakes, serving as a reminder of their terrifying origins as gorgon-like huntresses of the damned.

Myths About the Erinyes

The Erinyes are depicted in various Greek myths as avengers of family murderers. They chased the sorceress Medea after she brutally killed her brother Apsyrtus to aid herself and her lover, Jason, in escaping from her father. The Furies tormented Medea until her aunt, the powerful sorceress Circe, finally cleansed her. Despite being cleansed, some accounts suggest that the Erinyes avenged Apsyrtus by causing Jason to abandon Medea for a younger woman, which drove Medea to murder their children in retaliation.

The Erinyes play a crucial role in the story of Oedipus, who infamously killed his father and married his mother. Initially, Oedipus is unaware of his crimes, however, after a great famine and plague afflict Thebes, he discovers the truth. Some writers suggest that the Erinyes unleashed the famine to punish Oedipus for his blood guilt. Upon learning the truth, Oedipus blinds himself and abdicates as king of Thebes. His two sons, Polyneices and Eteocles, mock his decision, which prompts Oedipus to call on the Erinyes to curse and punish them. The Furies obliged, leading to the eventual deaths of Polyneices and Eteocles, who killed each other. Their conflict also catalyzed another prominent myth involving the goddesses of vengeance: the myth of Alcmaeon.

Alcmaeon

Alcmaeon was the son of Amphiaraus, a legendary seer and one of the notorious leaders in the war of the Seven Against Thebes. After Oedipus abdicated the throne, his sons Polyneices and Eteocles argued over who should rule the city, leading to Polyneices’s exile. He fled to Argos to seek the protection of King Adrastus. Together, they began recruiting men to launch a war to reclaim Thebes. They approached Amphiaraus to join the fight, however, he initially refused to participate because his prophetic abilities revealed that they would lose the war and die. Polyneices bribed Eriphyle, Amphiaraus’s wife, with Harmonia’s necklace, convincing her to persuade her husband to join the campaign. Against his better judgment, Amphiaraus entered the war but ultimately met his fate.

Alcmaeon held his mother responsible for his father’s death, which drove him to kill Eriphyle to avenge Amphiaraus. He also seized Harmonia’s necklace. The Erinyes pursued Alcmaeon for the crime of matricide, driving him into madness. He sought purification from his grandfather, King Oicles, in Arcadia but was denied. Eventually, he turned to King Phegeus in Psophis, who purified him and allowed him to marry his daughter, Arsinoe.

Alcmaeon gave Harmonia’s necklace to Arsinoe but even after being cleansed he continued to suffer the consequences of killing his mother. The land surrounding Alcmaeon became barren and infertile due to the wrath of the Furies and the blood guilt that polluted him. Some accounts suggest that it was not the Erinyes’ wrath but rather the curse of Harmonia’s necklace that led to the land’s desolation.

In search of a way to cleanse both his soul and the land, Alcmaeon visited the Delphic oracle. The oracle instructed him to find a land that did not exist at the time he killed his mother. Following this advice, Alcmaeon discovered a newly formed delta near the Achelous River. He settled there and married Callirrhoe, the daughter of the river god Achelous, leaving his previous wife, Arsinoe, behind.

Callirrhoe desired Harmonia’s necklace and urged Alcmaeon to return to Psophis to retrieve it. Upon entering Psophis, Alcmaeon was killed by Arsinoe’s brothers for abandoning her. After learning of Alcmaeon’s death, Callirrhoe asked Zeus to make her sons grow up instantly so they could avenge their father. Zeus granted her wish, and the boys killed Arsinoe’s brothers and parents before escaping to Tegea.

Orestes

The most famous myth about the Erinyes, prominent in art and literature, is the story of Orestes, the son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra. While sailing to Troy, Agamemnon offended Artemis by killing one of her sacred deer, causing the goddess to halt the winds and prevent the Greek ships from reaching Troy. Calchas, the seer, told Agamemnon that to appease Artemis and restore the winds, he needed to sacrifice his eldest daughter, Iphigenia.

After much hesitation, Agamemnon tricked Clytemnestra into bringing their daughter, Iphigenia, to him. Ultimately, he sacrificed her, which pleased Artemis and restored the winds needed for his fleet. Clytemnestra never forgave her husband for this horrific act. While Agamemnon fought for ten years in the Trojan War, Clytemnestra took a lover named Aegisthus, and together, they plotted his death. When Agamemnon returned, Clytemnestra and Aegisthus murdered him, finally avenging the death of Iphigenia.

After Agamemnon’s death, Orestes was either away or clandestinely taken from the palace to protect him from Clytemnestra. Years later, when Orestes reached adulthood, the oracle of Apollo commanded him to avenge his father’s murder. With the help of his sister Electra, Orestes sneaked into Clytemnestra’s palace disguised as a messenger, bringing news of his supposed death. This disguise enabled him to kill Clytemnestra and Aegisthus, avenging Agamemnon. Despite Orestes’s motives, the Erinyes pursued him relentlessly for committing matricide. They tormented him, ultimately driving him to madness by haunting him with visions of his deceased mother.

Orestes fled to Delphi to seek protection from Apollo. Although Apollo instructed Orestes to avenge his father’s death, the god of truth and prophecy could not shield him from the relentless pursuit of the Erinyes. Instead, Apollo directed Orestes to travel to Athens to request the first-ever murder trial, which would determine whether his actions were justified.

In this trial, Apollo served as the defense for Orestes, while the Erinyes acted as the prosecution. After considerable deliberation, the Athenian jury found itself evenly divided in its decision. Consequently, Athena intervened to deliver the final judgment, resulting in Orestes’s acquittal. This verdict allowed Apollo and Athena to cleanse Orestes of his crime and blood guilt, thus protecting him from the wrath of the Furies. The decision angered the Erinyes, who threatened to bring famine to the city. However, they were soon appeased when the Athenians promised to begin worshipping them.

Worship of the Erinyes

The Erinyes were revered throughout ancient Greece. Turtledoves and narcissus flowers were considered sacred to them. They had a temple located in a grotto near the Areopagus in Athens, close to where Athenians conducted murder trials. It was customary for individuals who were acquitted of murder to present offerings at the sanctuary of the Erinyes. Additionally, a sanctuary was dedicated to them in Colonus, located in Attica. At the center of this sanctuary was a grove that no one could enter.

They also had a sanctuary in Ceryneia, reportedly established by Orestes. According to the ancient writer Pausanias, anyone guilty of bloodshed, heresy, or impiety who enters the temple will be struck with madness and fear. Pausanias notes another temple in a sacred grove dedicated to the Erinyes along the Asopus River in Corinthia. They were also honored in Megalopolis in Messene under the name Maniai (madness).

Several cities hosted a festival in honor of the Erinyes called the Eumenideia. During this festival, people sacrificed black sheep, presented flowers instead of garlands, and offered nephalia, a drink of honey mixed with water.