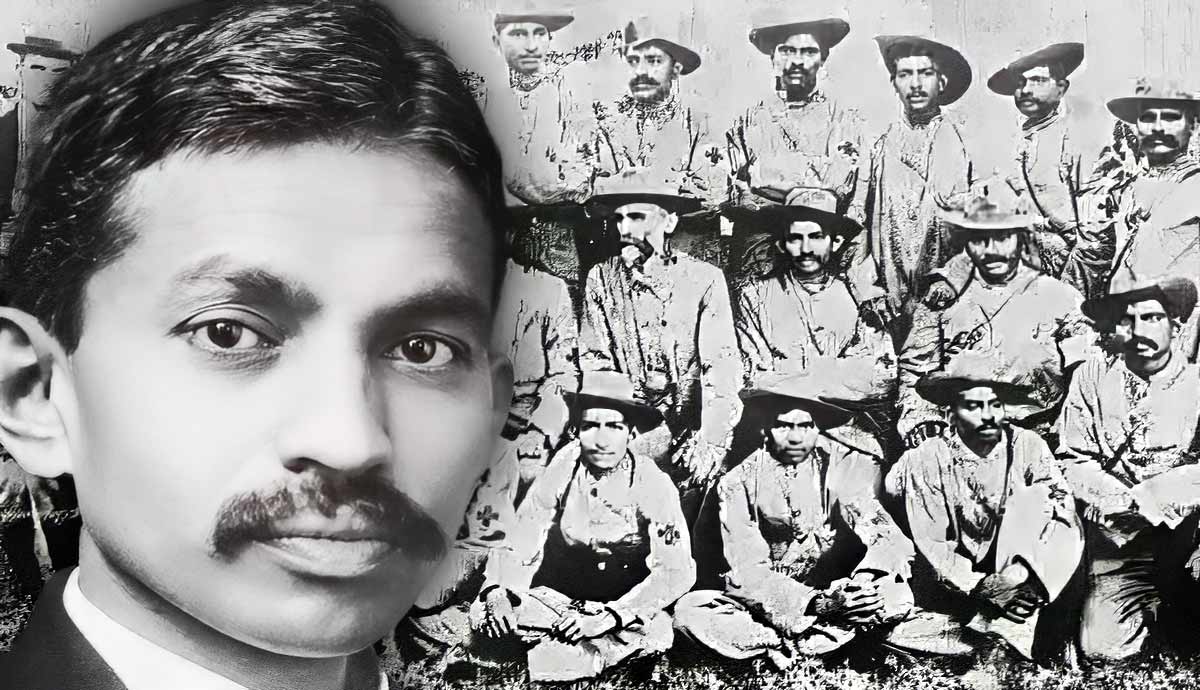

A striking figure in his loincloth and with a genuine smile on his face, Gandhi is pictured around the world in the popular imagination as a prominent leader of India and a statesman who championed peaceful methods of resistance (and governance) despite the use of violence by his enemies.

His story, however, was not limited to India. In his younger years, Gandhi practiced law in South Africa. It was there that he witnessed racism and violence. And it was there that his attitude, his beliefs, and his ideologies were formed.

The Influences in the Life of Young Gandhi

Born on October 2, 1869 in northwest India, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was the youngest of the four children between Karamchand Uttamchand Gandhi and his wife Pulitbai (his fourth wife).

His family was of the merchant caste, and his father was a civil servant, holding the powerful position of dewan (chief minister) of Porbandar State during the time of the British Raj. Karamchand also practiced law.

Mohandas’ parents were from a mix of different Hindu backgrounds, but it was his mother’s piety that had a notable effect on young Mohandas. She would never have a meal without saying her prayers and would often go days without eating anything, fasting for religious reasons.

In 1883, at the age of 13, Mohandas was married to Kasturbai Makhanji Kapadia, who was just 14 at the time. This arranged marriage significantly affected the development of Mohandas’ views. In 1885, his wife gave birth to their first baby, who died after only a few days. Soon after, the second child was also lost. She would later bear four children.

Gandhi Becomes a Lawyer

In 1888, several months after the birth of his son, Harilal, and after completing his schooling, Mohandas left India to study in England. Over the course of the next three years, he became a serious student, applying himself vigorously to obtain a degree in law. During this time, he also studied philosophy and devoted himself to understanding different religions.

During his time in England, Gandhi became a vegetarian, being heavily influenced by other students and friends around him who had adopted the lifestyle. Overall, his experiences in England helped to widen his horizons and gave him an open-minded perspective from which to view the world.

He finished his studies in 1891, after being called to the Bar, and returned home to India, where he attempted to establish himself as a lawyer. He opened a practice in Bombay, but he soon encountered difficulties, such as a lack of knowledge of the Indian legal system, which also had a detrimental effect on his self-confidence. His practice collapsed, but he was soon offered a position working for an Indian legal firm in the Transvaal in South Africa. The job was a 12-month contract, but Gandhi would end up staying much longer.

Gandhi Experiences Prejudice in South Africa

In 1893, Gandhi arrived in the port city of Durban, where he met with his employer, Dada Abdulla, for whom Gandhi provided legal counsel. It was not long before Gandhi had to undertake a train journey to the Transvaal capital of Pretoria. Before he got there, however, he would have an experience that would bring his attention to the racial injustices and the deep systemic problems inherent in this part of the world.

While in Pietermaritzburg in Natal, which was then a British colony, he bought a first-class ticket and proceeded to seat himself on the train. A white person objected to his presence and summoned the rail officers who ordered Gandhi out of the first-class section, claiming that non-whites were not allowed to be there. Gandhi objected and produced his first-class ticket, but this only angered the staff, who threw him off the train along with his luggage.

Later in the journey, while near Johannesburg, Gandhi was forced to sit outside on the stagecoach next to the coachman. At some point in the journey, the conductor got out of the stagecoach and produced a dirty rag which he spread on the footboard. The conductor then ordered Gandhi to sit on the rag while he took Gandhi’s seat to smoke a cigarette. Gandhi refused, and the conductor started beating him.

As he held tightly onto the rails, Gandhi took the blows, refusing to strike back. Witnessing this vile and unfair assault, the white passengers in the stagecoach forced the conductor to stop.

When he arrived in the Transvaal, his experiences with prejudice continued. Indians were treated even more poorly there than in Natal. They were not allowed to own property; they were subjected to curfews and had to carry passes. They were not even allowed to use the sidewalk. While breaking the latter law, Gandhi was assaulted by a policeman near President Paul Kruger’s house.

For his part, Gandhi did not simply resort to emotional outrage. Well-educated and a deep thinker, Gandhi pondered the question of how people could find joy in the poor treatment of their fellow human beings.

Gandhi Takes up the Fight for Justice

While in Pretoria, Gandhi became vocal in addressing the Indian people living there, awakening them to their plight and their rights. His first order of business was to take on the railways with regard to who could use first-class tickets. He was given assurances that Indians who had bought first-class tickets could use them if they were “properly dressed.”

Despite this victory, legal measures against Indians continued to be implemented across Boer and British territory. Discrimination was becoming codified in law (which would later evolve into apartheid).

In April 1894, Gandhi traveled back to Durban and prepared to set sail for India. A friend of his showed him an article in the Natal Mercury that described a new bill to be introduced that would severely degrade the rights of Indian citizens. Gandhi realized that he could give significant aid to the Indian community by organizing resistance against this bill, and despite desperately wanting to return home to his wife and son, Gandhi did what he thought to be the most moral path and stayed.

Gandhi organized massive petitions that garnered thousands of signatures, protesting the abuse of Indian people in South Africa. Despite the bill still being passed, Gandhi’s efforts brought him widespread attention as far afield as Britain and India.

After the bill had been passed, organized opposition to it continued. Gandhi enrolled as an advocate of the Supreme Court of Natal. With his excellent writing abilities, he was a significant asset in compiling petitions and writing letters that were sent to authority figures in South Africa as well as in India.

In 1894, he formed the Natal Indian Congress, a political organization dedicated to fighting and maintaining the rights of Indians in South Africa.

As the months passed, Gandhi became more prominent and widely known throughout Natal. In 1996, he traveled to India as part of an organized campaign to meet with authorities and spread his message to the Indian people. The British government, swayed by Gandhi’s efforts, blocked the Franchise Bill in Natal. This caused a backlash in the colony, and anti-Indian sentiment increased among the white population. A misinformation campaign followed, exaggerating Gandhi’s desires, and the white population of Natal believed that Gandhi wanted to swarm the Natal Colony with Indian people.

Gandhi Returns to South Africa

When Gandhi returned to South Africa with his wife and children, the ship he was on was held for 23 days, as the Natal populace believed it was carrying hundreds of Indian immigrants in what would represent the first wave of “Indianisation.” The white colonials even threatened to kill the Indian immigrants. When Joseph Chamberlain, the British Secretary of States for the Colonies, heard of this development, he ordered the prosecution of all who were responsible, but Gandhi refused to identify any of the offenders, claiming that they had been misled and if they knew the truth, they would feel regret for what they had done.

Over the next few years in South Africa, Gandhi became more dedicated to the ascetic lifestyle. He refused luxuries and lived as simply as he could and in the service of others.

When the Second Anglo-Boer War broke out, Gandhi advised the Indians to support the British cause. His reasoning for this was that since the Indians were trying to claim their rights as British citizens, they should give their support to the British Empire in the hope of being noticed for their efforts. Gandhi, however, personally sympathized with the Boer cause.

Gandhi helped form the Indian Volunteer Ambulance Corps, which served throughout the duration of the war. After the war, Gandhi returned to India, where he involved himself in politics, but he was not long in his mother country before he was asked to return to South Africa.

At this time, as a result of the British victory in the Second Anglo-Boer War, all of South Africa came under British control. This lasted until 1910, when the Union of South Africa was formed, a state with significant independence and was not subject to rule from London. It was, effectively, an independent country.

Gandhi Returns to South Africa Again

Gandhi returned to South Africa because Joseph Chamberlain was visiting South Africa, and the Indian community needed Gandhi to argue their case for them. Chamberlain was put in a difficult position; he was given a gift of 35 million pounds from the European sector of South Africa. Had he acceded to Gandhi’s requests, he would have angered his benefactors. And so Gandhi left the situation empty-handed.

Meanwhile, however, the plight of the Indian community in the Transvaal was worsening, and Gandhi decided to travel to Johannesburg, where he stayed to help the Indian community. In 1903, he helped the British Indian Association, which was fighting the planned eviction of Indians who were British subjects.

During this time, he established his own newspaper, the Indian Opinion. In 1904, Gandhi moved back to Natal (now a province of the Union of South Africa), where he opened a commune named Tolstoy Farm, centered around the production of the newspaper. Following his ascetic virtues, he took a vow of abstinence known as brahmacharya, which forbade all sexual relations, even spousal. By 1906, he had refined his idea of Satyagraha, the concept of passive resistance. This idea would confound his enemies, for under this belief, he, and the adherents to the idea, would not physically fight, thus removing the justification for his enemies to use violence and exposing their brutal tendencies, which degraded their position from a moral perspective. The goal was to remove anger from the victim, and instead of focusing on there being a winner or loser, the situation would be resolved through the realization of appealing to a universal humanity.

With the adoption of Satyagraha, Indians in South Africa refused to obey the unjust laws to which they were subjected. Mass arrests were made in 1907 following the refusal of Indians to be fingerprinted and carry registration papers which were requirements of the Indian Registration Act of 1907. Amid non-violent protests, Gandhi was arrested in 1908 and imprisoned for two months. He would serve more sentences over the coming years, and after a seven-year-long fight, the law was eventually repealed.

During these seven years, there would be suffering, political betrayal, and broken promises from the authorities, especially from General Jan Smuts, who led the government’s attempts to subdue the resistance. Despite the hardships, Gandhi never showed any anger towards his oppressors. After a series of crippling strikes, Smuts eventually relented and repealed the act. Gandhi sent him, as a gift, a pair of sandals that he had made in jail.

In 1914, Gandhi prepared to return to India, but the outbreak of the First World War saw him diverted to England, where he formed another ambulance corps to serve the wounded.

Gandhi’s experiences in South Africa shaped the man he became, and it was there that he won significant fame, becoming well known not just in South Africa but in the United Kingdom and, importantly, in India, whereupon his return, he enjoyed a huge groundswell of support.

Gandhi’s non-violent methods were created and proven in South Africa. They worked. As a result, his years in South Africa are remembered as incredibly important to what he would achieve later in life.