In Orwell’s famous essay “Why I Write,” he claims, “Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness… that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.”

Orwell believed he was meant to write; it was not something he had a choice in. Rather, it was in his nature. It begs the question – what was Orwell doing between the ages of seventeen and twenty-four, and how did that influence his literature and later life?

From Boyhood to Eton

George Orwell was not born as such; his given name was Eric Arthur Blair. He was born on June 25, 1903 in India, the son of Ida and Richard Blair, who worked in Bengal as a Sub-Deputy Opium Agent in the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service, a key part of the bureaucracy that made up the British Empire. He lived there only briefly, returning to the United Kingdom when he was one year old as his older sister Marjorie was to be educated in England, as was the custom at the time. Therefore, he spent the majority of his childhood in the Oxfordshire market town of Henley-on-Thames.

Orwell recalls his childhood home in his fourth novel, Coming Up for Air, where he describes “the great, green juicy meadows round the town… And the dust in the lane, and the warm greeny light coming through the hazel boughs.”

The bucolic paradise that Orwell paints in Coming Up for Air has long been considered by scholars to be influenced heavily by the impressions of his childhood. Michael Shelden notes in his biography of Orwell that “Like young George Bowling [the protagonist in Coming Up For Air] Eric was not really a welcome companion among the older boys.”

In many ways, he was a stray among the middle-class inhabitants of Henley-on-Thames. He was introspective and imaginative and found it difficult to make friends his own age. Furthermore, he was forbidden by his class-conscious mother from playing with their more working-class neighbors’ children.

Class struggle and money would continue to be a major feature of Orwell’s life. In Road to Wigan Pier, Orwell described his upbringing to be “what you might describe as the lower-upper-middle class.” He went on to say that those in his class were members of the “landless gentry:” “People in this class owned no land, but they felt that they were landowners in the sight of God and kept up a semi-aristocratic outlook by going into the professions and the fighting services rather than into trade.”

Class in Britain is more complicated than the accumulation of one’s income. One’s class is really the product of one’s experiences, values, and education. Orwell’s family subsisted on his father’s £600 annual salary, which was not paltry in Edwardian England but certainly not a gigantic sum. However, his father’s career in India made him a colonist, and his parents’ insistence on his education at St Cyprian’s, and in 1917, his scholarship to Eton College (the most prestigious and expensive public school in Britain) meant that he was constantly surrounded by the upper-classes. This had a profound impact on him and can be seen throughout his journalism and novel writing.

Orwell did not loathe Eton in the same way that he loathed St Cyprian’s. Scholar John Carey notes in his introduction to the Collected Essays of Orwell that “as a scholar, living among other scholars, he was insulated to a certain extent from humiliating comparisons.”

It has been documented that Orwell’s time at Eton reinforced several political and philosophical convictions he took into adulthood. Eton encouraged his brand of anti-intellectualism, his antipathy towards pacifism, and his admiration for the “military virtues.”

Most people recognize Orwell to be a vocal supporter of left-wing politics, and that is true; however, in many ways, his temperament was decidedly more conservative. It is most likely that, as a young boy, his opinions about social issues were formed at Eton. While there were watershed moments in his adult life that shaped his writing and beliefs, such as the years he spent in Burma (now Myanmar) and his time spent among the homeless in Paris and London, he kept a hold of a very specific brand of social conservatism that he most likely learned at Eton.

From Imperialism to Democratic Socialism

One would expect a King’s Scholar at Eton to go straight to King’s College, Cambridge to study Classics. Orwell defied expectations, instead joining the Imperial Police force in Burma. His lack of university education may, in part, have been due to a lack of funds; it might also have been one of his very first acts of class rebellion. However, it is also a move that we can assume stemmed partially from his father’s influence, who spent decades in the colonies. This career choice may also have been an attempt to regain some glimpse of his idyllic early childhood as he moved back East.

There is a lot of speculation about Orwell’s life in Burma. Much scholarship suggests that he was unanimously miserable in the colonies and saw right through the exploitation of the British Empire. However, it is safer to assume that Orwell was in two minds about his position of authority within the British Empire.

In his essay “Shooting an Elephant,” he describes his ambivalence in all its brutality: “I thought of the British Raj as un unbreakable tyranny… with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priest’s guts.”

Orwell was critical of the Empire, but we must also acknowledge how much he benefited from it. After all, he rose through the ranks to become the head of the police force in Twante and is said to have had many enjoyable relationships with the native people, specifically the women he found there.

Orwell left his career as an Imperial Police Officer in 1927, a move many have construed as an act of rebellion against imperialism. There might be some element of this; but it is also true that he was restless to write, to become an author, and so some of his motivation was selfish. As Shelden noted, “He was frustrated by the thought that he was so far away from the literary world.”

And so, Orwell returned to England, living with his parents in the rural seaside town of Southwold, vastly different from the rainforests of south-east Asia. He settled down there to write, and write he did; within a year, he was a published author, and within four years, he had finished his first novel.

Robert Colis says in his biography of Orwell, English Rebel, that Orwell “did not want to just write, he wanted to get under the skin of those he wrote about, as close to the grey-skinned experience as he thought he could stand,” and is clearly evidenced by his output.

Between 1928 and 1937, Orwell published many articles in the Adelphi, a literary magazine he regularly read during his time in Burma. He had researched deeply into the lives of the extreme poor, living as a pauper in London and Paris; his experiences would pour into Down and Out in Paris and London, finished in 1930 but not published by Gollancz until 1933 and Road to Wigan Pier, published in 19837, by the Left Book Club and then later by Gollancz.

Contrary to popular opinion, not everything Orwell wrote was overtly political; however, everything he wrote made some greater point about English society, class struggle, and the nature of art. Coming Up for Air and Keep the Aspidistra Flying are two novels that borrow much from Victorian realism; indeed, Orwell said in “Why I Write” that he had a desire to “write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes.”

Although not enormous by any means, Coming Up for Air and Keep the Aspidistra Flying both conform to this description. However, as Orwell himself delineates, “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism.”

From one War to Another

The Spanish Civil War was to prove the most fundamental political experience of Orwell’s life. Orwell arrived in Barcelona in 1936 to pledge his allegiance to the Second Spanish Republic. He spent six months there, flitting between his wife Eileen and the Aragon front line, fighting alongside his Spanish comrades.

However, it all ended abruptly on May 20, 1937, when he was shot in the neck. He wrote in Homage to Catalonia that “roughly speaking it was the sensation of being at the centre of an explosion. There seemed to be a loud bang and a blinding flash of light all round me, and I felt a tremendous shock — no pain, only a violent shock.”

He spent almost a month in hospital and was lucky to survive. Little did he know that his near-fatal injury would be the last of his worries, as, on June 19, the Republican security forces of Spain identified him as a spy, and he was forced to leave Spain.

Orwell went to Spain as an out-and-out anti-fascist; he left it as an out-and-out anti-communist. It is his giant swings across the pendulum of political belief that often leave people confused as to his true political opinions. However, if there is one thing that Orwell remained throughout his life, it is his staunch anti-intellectualism.

What he saw in Spain, he also saw when writing Road to Wigan Pier, a socialism that did not need its “slick little professors” to tell it what it is. The next chapter of Orwell’s life was engulfed by the Second World War, although he did write Coming Up For Air in the intervening eighteen months between the end of his involvement in the Spanish Civil War and Chamberlain’s declaration of war against Hitler’s Germany.

Orwell joined the Home Guard in 1940 and spent three years there. He was never required to fight; the closest he came to warfare was his experiences in the Blitz; poet Cyril Connolly, who spent one of the first nights of the Blitz with Orwell in his own Piccadilly flat, said of Orwell: “He felt enormously at home in the Blitz, among the bombs, the bravery, the rubble.”

Regardless of the destruction going on around him, Orwell’s career progressed significantly in the latter stages of 1940. In December 1940, he received an invitation to write from the Partisan Review, one of the most influential magazines in the United States at the time.

Furthermore, written in 1941, “The Lion and the Unicorn” helped to spread Orwell’s fame as an eloquent spokesman for democratic socialism. It expressed his opinion that the outdated British class system was hampering the war effort and that to defeat Nazi Germany, Britain needed a socialist revolution.

It was on the back of this fame that he was offered the position of Talks Assistant at the BBC. India had an army of over two million men, and Orwell was part of the effort to transmit propaganda to the sub-continent to encourage the view that Britain’s security was of vital importance to the Indians.

That Orwell would be so integral to the propaganda efforts of Britain, especially in the Imperial provinces, would surprise many who see his political novels as the very antithesis of such things. Orwell was willing to write such things because he believed that this job constituted his contribution to the war effort.

However, he soon realized that his efforts were futile. Shelden recounts that a survey within the BBC showed that, in a country of nearly three hundred million at the time, only 150,000 had the technological capacity to tune into the Eastern Service. Of these, probably only a handful were listening to anything other than the news.

The news affected him deeply, as Shelden recounts, he said privately: “Much of the stuff that goes out from the BBC is just shot into the stratosphere, not listened to by anybody, and known to those responsible for it, not to be listened to by anybody.”

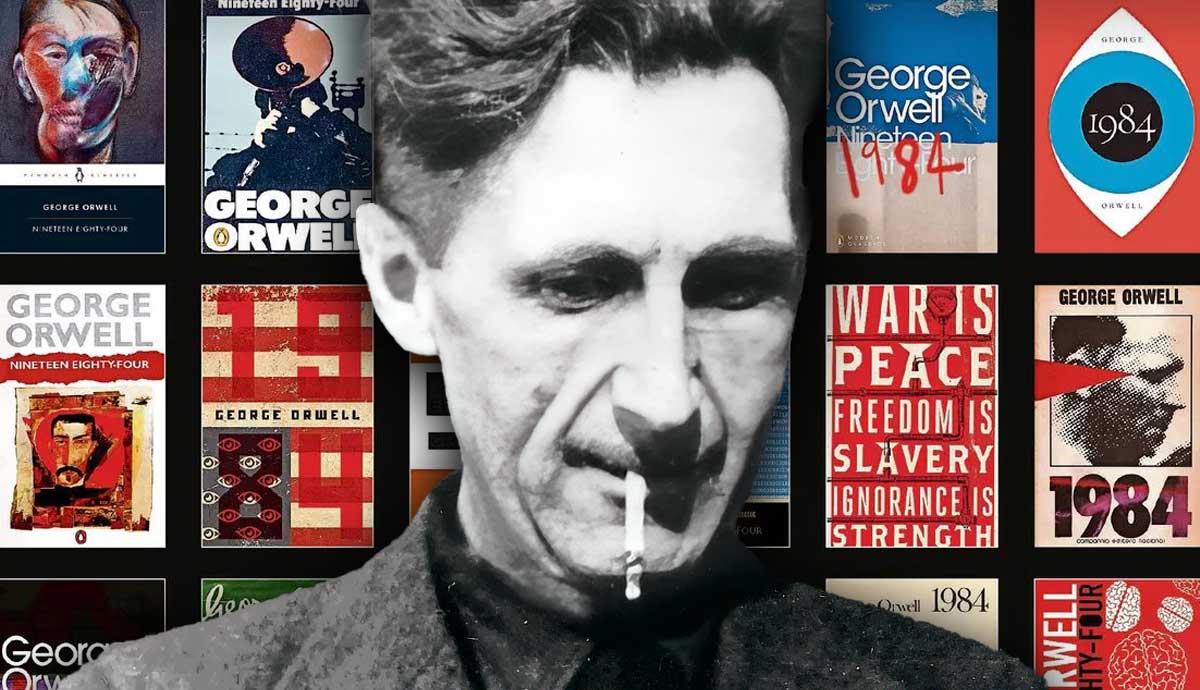

It is these experiences that would later pour into 1984. The things he experienced at the BBC eventually proved useful to him when he drew inspiration from them for his creation of the nightmare bureaucracy of the Ministry of Truth. Having never worked in such an environment, it gave him enough knowledge of how organizations create justifications for meaningless activities and persuade many of their workers to take the work seriously.

Towards the end of the war, Orwell’s life was marred by personal difficulties. Orwell’s mother Ida died of heart failure, and Shelden argues that this may have been a catalyst for his yearning for a child. Orwell expressed in his private diaries that he had longed for a child but thought himself to be infertile, although Shelden has pointed out that it cannot be known whether this was true.

It is out of this grief that Orwell and his wife Eileen came to adopt Richard Horatio Blair. Michael Shelden notes that Eileen was initially doubtful of their decision to raise a child if they could not have one of their own. However, it became clear that both new parents doted on their new offspring, and David Astor, the infamous editor at The Observer, had the impression that George and Eileen were “renewing their marriage ‘round their new child,” as quoted by Shelden.

It was around this time that Animal Farm was published, a novel that led him to global fame and shaped the rest of his career. D J Taylor notes in Orwell: The Life that Orwell’s reaction to the success of this political fable was an amalgamation of satisfaction and unease. Although, in terms of wealth and literary fame, his life would never be the same again, he was nervous that a left-wing critique of Stalinism might be misrepresented as an attack on Socialism itself.

Largely, his fears came true, and the most enduring criticism of the book was that any kind of criticism of the Soviets was playing into the hands of the Nazis. Once more, D J Taylor recounts that Orwell thought that this phrase was “a sort of charm or incantation to silence uncomfortable truths.” What he had set out to do was simply make a forceful attack, in an imaginative way, on the sustaining myths of the Soviet Union.

1945 to 1984

In the latter stages of Orwell’s life, his personal tragedies began to invade his professional career. In 1945, just as Animal Farm was gaining global notoriety, Eileen Blair died after an operation she was hoping would quell her ailing health. Orwell was abroad at the time; he flew straight back upon hearing the news.

Curiously, the idea that Orwell was not moved by the death of his wife has pervaded tales of their relationship. However, this could not be further from the truth. The letters he penned during this period show a shell-shocked and sorrowful man, inhibited by his own stoical disposition. He was left with a child to take care of and many regrets about the way he had treated Eileen at times. It would do a disservice, to Orwell but particularly to Eileen, to think of their life together as anything other than filled with love, although the love a troubled writer in the nineteen-forties has to give often leaves much to be desired by modern standards.

However, it was true that Orwell was keen to remarry. As Shelden notes, with a young child at his feet and a history of weak lungs, he felt a strong desire to be taken care of. According to Shelden, he courted many younger women in the aftermath of Eileen’s death, most notably Celia Paget, Sonia Brownell, and Anne Popham. They all refused him, mostly on the grounds that none of them found him in the least bit attractive or had the remotest desire to become a wife, all being in their mid-to-late twenties at the time.

Eventually, however, one of the aforementioned ladies did accept his proposal. This took place four years’ later, in 1949, when Orwell was widely considered to be on his deathbed. Sonia Brownell married Orwell from his hospital bed at University College Hospital in London and were together for only a few short months before his death.

Although impending death loomed over Orwell’s last years, he did manage to finish 1984, and he did live to see its publication. The book’s publishers, Secker & Warburg, were haunted by the initial typescript, calling it “amongst the most terrifying books I have ever read,” as quoted by D J Taylor.

Just as with Animal Farm, there were concerns that the novel presented a direct attack on socialism in general and that the book was worth a million votes to the Conservative party, as D J Taylor recounts. In the face of such criticism, Orwell was always keen to stress that the moral was not strictly anti-communist but rather anti-totalitarian.

In the autumn of 1949, there were 25,000 copies of 1984 in print, and sales were booming in England and the United States. Although there were murmurings that the newly published novel had all of the hallmarks of a classic, Orwell would never live to see the rumors realized. On January 21, 1950, an artery burst in Orwell’s lung at the age of forty-six, and he passed away moments after.

Further reading

Carey, John. Collected Essays, ‘Introduction’ (London: Everyman’s Library, 2002).

Colis, Robert. George Orwell: English Rebel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Shelden, Michael. Orwell (London: William Heinemann, 1991).

Taylor, D J. Orwell: The Life (London: Chatto & Windus, 2003).

Williams, Raymond. George Orwell (London: Penguin, 1971).