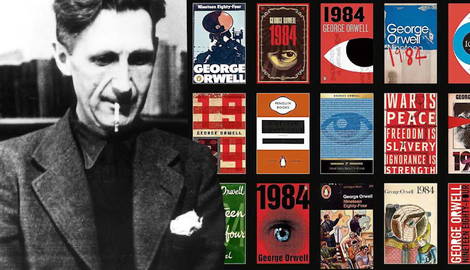

Some consider George Orwell’s political beliefs to be equivocal at best and suspicious at worst. D.J. Taylor recounts that there were concerns that 1984 “was worth a million votes to the Conservative party.” It is true that he held a specific but ever-changing set of beliefs that did not comply with mainstream left-wing thought. However, Orwell was always keen to stress that the moral of the novel was not anti-communist but rather anti-totalitarian, and he remained committed to his vision of democratic socialism throughout his adult life.

Orwell on Empire

Part of the reason for the confusion surrounding Orwell’s political beliefs was his readiness to criticize his peers on the left. It was Bernard Crick, Orwell’s foremost biographer, who said of him: “He made his name as a journalist by his skill in rubbing the fur of his own cat backwards.” Orwell was bold in his critique of left-wing thinkers, even though he himself was committed to left-wing politics. He did not believe in tribalism—he would not favor certain opinions because it was fashionable to do so as a left-wing intellectual living in the south-east of England. He was a man of principle and refused to partake in the petty politics that often had its roots in class division and snobbery.

That being said, he understood where his loyalties lay. While he was discerning in his critique of liberal left-wing politics, particularly in relation to foreign policy, he did not cross the line to support conservatism. Alex Zwerdling gives the example in his book Orwell and the Left of when Orwell was asked to address a meeting protesting Soviet pressure on Yugoslavia by a Conservative group in 1945. Orwell declined, even though he agreed for the most part.

“I belong to the Left and must work inside it,” he later said, “it seems to me that one can only denounce the crimes now being committed in Poland, Yugoslavia etc if one is equally insistent on ending Britain’s unwanted rule in India.”

Ever the pragmatist, Orwell understood the dangers of aligning himself with a more Conservative viewpoint, even if he agreed with parts of their philosophy. Ultimately, he simply refused to be a hypocrite; we can see this in his refusal to stand on the side of those who advocated Imperial policy in the East.

And he was well acquainted with Imperialism in Asia. In 1922, the year often heralded as the apex of modernism–with James Joyce’s Ulysses and T.S Eliot’s The Wasteland being published within a few short months of each other–Orwell was not eyeing literary stardom. Rather, he joined the Burma police force as a fresh-faced eighteen-year-old and rose to the ranks of Assistant District Superintendent.

As a member of the Burmese police force, he was responsible for administering the full might of British Imperial rule, and at different points, he both relished and regretted the part he had to play in European colonialism.

Orwell’s ambivalence about empire is illustrated in his essay “Shooting an Elephant,” about the true story of his shooting an elephant at the behest of the village locals where he was stationed in Moulmein, lower Burma (now Mawlamyine, in lower Myanmar). Talking about the hatred he endured at the hands of the Burmese people, he said that “all of this was perplexing and upsetting. For at that time, I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing and the sooner I chucked up my job and got out of it the better.”

However, with the brutal honesty we have come to expect in Orwell’s journalism, he spoke openly about his conflicting opinions. Later in the same passage, he admits that “with one part of my mind I thought of the British Raj as an unbreakable tyranny… with another part I thought that the greatest joy in the world would be to drive a bayonet into a Buddhist priests’ guts. Feelings like these are the normal by-product of imperialism.”

Orwell sheds light on the internal turmoil he felt, as well as many other British citizens when faced with the realities of empire. He was aware of his prejudices; he fought and challenged them, but he was also remarkably honest in the depth of his feelings. Some find this honest equivocation confusing when discussing Orwell’s political beliefs. Readers are not often presented with such strongly opposing opinions simultaneously in the space of a few sentences. However, what readers must take into consideration is Orwell’s commitment to honesty in his writing. He did not want to present a certain image of himself, one that might please left-wing intellectuals or the upper-middle ruling classes.

Orwell on Conservatism

“Shooting an Elephant” was published in 1936. Coincidentally, or perhaps not, this was the same year Orwell confirmed his commitment to democratic socialism. 1936 was the year the Spanish Civil War broke out; he wrote to Cyril Conolly a year later that “I have seen wonderful things and at last really believe in Socialism.”

In “Why I Write,” published a decade later in 1946, he said, “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.” These quotations are emphatic in their commitment to left-wing politics. However, the quote also acknowledges that such loyalty was not always the case.

It is true that Orwell was not always on the political left, and even when he was, he exhibited many opinions that would not echo the sentiments of today’s left-wing political thinkers. The young Orwell described himself as a “Tory anarchist,” as he was not comfortable with the idealistic orthodoxies of the left.

Robert Colls argues that Orwell was, at heart, a Burkean Conservative. In his interview with the Oxford Academic, he argues that Orwell’s affections lay in “the little worlds” outside of the State apparatuses that left-wing academic theorists were so keen on dismantling.

Conservatism is, as the name suggests, concerned with the preservation of a certain way of life. It is a doctrine that relies on tradition and carefulness in its worldview. These are qualities that Orwell, at many points in his life, expressed admiration for.

For example, in his 1940 review of Muggeridge’s The Thirties, Orwell writes: “It is all very well to be ‘advanced’ and ‘enlightened,’ to snigger at Colonel Blimp and proclaim your emancipation from all traditional loyalties, but a time comes when the sand of the desert is sodden red and what have I done for England, my England?” Here, Orwell expresses a very primal and patriotic streak in his personal outlook.

He continues, “I was brought up in this tradition… even at its stupidest and most sentimental it is a comelier thing than the shallow self-righteousness of the leftwing intelligentsia.” In this quotation, Orwell plays sentimentality against the leftist intelligentsia; he does so knowingly, as he bristles against the snobberies and privileges he saw as typifying the social elite at that time.

He demanded that his literary peers live up to their own principles; he had a strong dislike for those who would claim sympathy for the working classes without taking the time to acquaint themselves with their realities. Orwell was, even after 1936, anti-intellectual. He spoke for the working-class way of life.

However, he did so as a man who attended Eton College, the most expensive public school in Europe at the time—albeit on a full scholarship—and had a very typical white upper-middle-class upbringing in India as the son of a British civil servant. It has been documented that Orwell’s time at Eton reinforced several political and philosophical convictions he took into adulthood.

Eton encouraged his brand of anti-intellectualism, his antipathy towards pacifism, and his admiration for the “military virtues.” As argued above, Orwell was a vocal supporter of left-wing politics; however, in many ways, his temperament was decidedly more conservative. It is most likely that, as a young boy, his opinions about social issues were formed at Eton.

Orwell on Pacifism

On his way to fight in the Spanish Civil War in 1936, Orwell stopped in Paris to meet a man for whom he had conflicting feelings. Henry Miller, author of the infamous novel Tropic of Cancer, told Orwell “in forcible terms, that to go to Spain was the act of an idiot,” as Orwell himself recalled in his famous essay “Inside the Whale.” Speaking at their meeting, he says that “[Miller] felt no interest in the Spanish war” and that when discussing the bleak state of civilization, Miller was unmoved by the prospect of society being destined to be swept away.

Orwell was appalled by Miller’s attitude. It infuriated and perplexed him. Miller, at this time, had declared his position as an extreme pacifist, refusing to fight or to convert anyone else to fight. Orwell questioned the morality of this, asking what exactly Miller could be so accepting of during a time characterized by “fear, tyranny, and regimentation.” To accept civilization, Orwell laments, is to accept decay. Orwell does not manage to change Miller’s mind, but he remains mystified by Miller’s philosophy, and it is in this mystification that we can identify Orwell’s politics as one of action.

The essay’s title, “Inside the Whale,” refers to the Biblical tale of Jonah and the Whale; Orwell likens Miller to a “willing Jonah,” someone who has been swallowed by their own viewpoint and has no desire to look outside of it. Miller, after all, quit his job working at the Western Union to move to Paris and write, completely uninhibited, in the Latin Quarter of Paris among the artists and the vagabonds.

Miller’s story is one characterized by escape, obscuration, and disavowal of his own responsibilities. This is the opposite of Orwell, who was always running toward the center of things, whether that be war in Europe, empire in Southeast Asia, or poverty in northern England.

Orwell sees Miller as a man whose prose and philosophy belong to the 1920s rather than the 1930s. Miller was writing about the lumpen-proletarian fringe of Parisian society during a time when the intellectual foci of the world were in Berlin, Rome, and Moscow.

Orwell writes, “A novelist is not obliged to write directly about contemporary history, but a novelist who simply disregards the major public events of the moment is… a plain idiot.” Therein lies Orwell’s ultimate opinion of Miller: a nostalgic fool. It is not even that Orwell is unsympathetic to Miller’s attitude; he himself had spoken about his teenage impulse to write “enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their sound.”

However, he also believes that “no book is genuinely free from political bias,” and it is that political impulse that ultimately drives him to write. Writing without some political lens, for Orwell, is either impossible or pointless.

Orwell on Ideology

The clearest distillation of Orwell’s political impulse to write can be found in The Road to Wigan Pier and Down and Out in Paris and London. In a way, trying to uncover Orwell’s political beliefs is futile because he evaded traditional labels in that sense. Rather, one must look to the green pastures of England to see what Orwell was really driven by.

As Robert Colls explains, “in 1936, [Orwell] went north and for the first time in his life found an England he could believe in. He saw how the miners kept the country going. He pondered why their labour was the most valuable, but not the most valued.”

Orwell felt a strong sense that real life existed in the mining communities and industrial conditions the working classes kept, especially in the north of England, although he wrote at length about the underclasses in London too.

When Orwell left Burma and returned to England to settle and write, he “did not want to just write, he wanted to get under the skin of those he wrote about, as close to the grey-skinned experience as he thought he could stand.”

And when Orwell famously wrote in The Road to Wigan Pier that “the lower classes smell” (a choice of words that earned him considerable criticism from the book’s eventual publisher Victor Gollancz – Gollancz was one of those left-wing intellectuals Orwell sneered at, although he was published by him many times), he did so as an act of rebellion against the liberal elite rather than to taunt the poor.

He knew that such brutal honesty would be frowned upon by his peers precisely because that was what they thought, but felt it improper to say. Orwell felt frustrated by what he saw as this hypocrisy; they held so many beliefs and opinions that they failed to voice because they ought not to. In fact, it was the concept of belief itself that left Orwell wanting. In “Writers and the Leviathan,” Orwell wrote that “to accept an orthodoxy… is always to inherit unresolved contradictions.”

He saw political belief as detrimental to literary integrity. He began “Writers and Leviathan” with the statement: “This is a political age. War, Fascism, concentration camps, rubber truncheons, atomic bombs etc, are what we daily think about, and therefore to a great extent what we write about.”

Equally, in many other essays, he saw political purpose as inseparable from literature. It is difficult for the reader to reconcile these two views, which is kind of Orwell’s point. The reader should be willing to sit with contradiction—both the writer and the citizen should not attempt to find concordance where there is none.

That is the thread that runs through so much of Orwell’s scribblings—whether he be speaking about Empire, Tory anarchism, or pacifism. There is nothing to make sense of. Orwell plays with contradiction, not only in his journalism but also in his fiction.

After all, in 1984, he famously created the notion of doublethink. In 1984, contradictory statements were how the State controlled its citizens. In Orwell’s non-fiction, holding two separate opinions simultaneously is the predominant manifestation of political orthodoxy. He writes that “to accept an orthodoxy is always to inherit unresolved contradictions… Take the fact that it is impossible to have a positive foreign policy without having powerful armed forces.”

What is the solution Orwell sees to ideological orthodoxy in the literary sphere? He argues in “Writers and Leviathan” that “to yield subjectively, not merely to a party machine, but even to a group ideology, is to destroy oneself as a writer.” However, he argues this is necessary, not as a writer, but as a citizen. Therefore, what Orwell concludes is that a writer should separate their politics from their literary life.

He argues, “When a writer engages in politics, he should do so as a citizen, as a human being, but not as a writer.” For Orwell, being a writer is more than being human; humanness is inextricably linked to an active political life. Orwell toed the line between politics and humanness—whether he did so to his satisfaction is a question only he can truly answer.

Further reading

Carey, John. Collected Essays (London: Everyman’s Library, 2002).

Colls, Robert. George Orwell: English Rebel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Crick, Bernard. George Orwell: A Life (London, Penguin Books, 1992).

Taylor, D.J. Orwell: The New Life (London: Constable, 2023).

Zwerdling, Alex. Orwell and the Left (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1974).