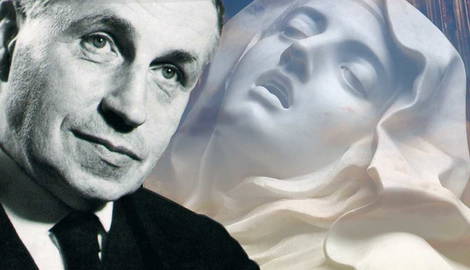

Georges Bataille’s writing stretches between fiction and theory, philosophy and political economy, but much of it contributes to a common project: the serious theorization and interrogation of eroticism and sexual taboos. In Georges Bataille‘s Erotism he includes a subtitle, ‘sensuality and death.’ This is a clue to the book’s central idea; and its oft-used cover, a photo of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, is another one. Erotism weaves the threads of eros, death, and religion into a common pattern, attempting to uncover the drives and experiences common to these apparently disparate parts of life.

More broadly, Bataille’s project involves uncovering unlikely, or disguised, commonalities and continuities between drives and experiences: horror and ecstasy, pleasure and pain, violence and affection. Bataille seeks to move past taboos and conventions in philosophical thinking, particularly ethical and religious doctrines, and to find truths in much-maligned libertine thinkers.

Georges Bataille’s Erotism: Sadism and Libertinism

In particular, Bataille was interested in the Marquis de Sade, whose writings – most notably Justine (1791) and the posthumously published The 120 Days of Sodom (1904) – pushed at the limits of taste and acceptability. Sade variously ignored and transgressed taboos surrounding depiction of sex and violence, populating his novels with litanies of explicit sex acts and brutal torture, explicitly inverting prevailing moral codes and upholding evil and cruelty as a virtue. Sade’s fascination with these two kinds of taboo – those relating to sex and those relating to cruelty and violence – are not separate but intimately connected, a fact which both deepens their transgressive weight and lies at the heart of Bataille’s interest with him.

The libertine tradition – a fuzzy collection of writers and historical figures united by their disregard for conventional morality, sexual inhibitions, and legal strictures – stretches back far beyond Sade, but finds its apotheosis in his celebration of suffering, and his elevation of forbidden or taboo sexual practices. Much of Sade’s writing is also explicitly blasphemous: playing with the membrane between the sacred and the profane in ways that invert or confuse these categories.

Bataille’s philosophy is also interested in the boundaries between sacred and profane things but diverges from Sade’s in its more explicit reconfiguration of the two. For Bataille, sex and death (and the violence which tends towards death) are definitively sacred things, while the profane world contains all those daily practices which involve moderation and calculation, restraint and self-interest. The profane world is a world of discontinuous beings, separated from one another by the borders of their minds, and the sacred world is the one where those borders are forgotten or dissolved.

Continuity and Discontinuity

The idea of Sade’s which Bataille returns to time and time again in Erotism, is that murder constitutes the height of erotic intensity – is in some sense the telos of sexual excitement. Much of Erotism is dedicated to explaining and maintaining that claim, in a system which entangles religion, sex, and death as achievements of the same underlying aim.

That aim has to do with overcoming discontinuities between individuals. Bataille points to reproduction and to the moment of birth as an original disjunction between individuals. In the act of sexual reproduction (which Bataille contrasts with the asexual reproduction of some other organisms), there is a necessary acknowledgement of discontinuity between parent and offspring, of a gulf which separates one thinking, sensing subject from another. This discontinuity persists in life, providing the boundary between oneself and others, but also constitutes a kind of isolation.

For Bataille, Sade’s link between murder and eros is not an isolated or arbitrary occurrence, but rather the mark of a common endpoint, the elimination of discontinuity. For Bataille, eroticism, death, and religious ritual (specifically sacrifice) all involve the destruction of the discontinuous subject and the achievement of continuity. In death and in the observation of death, we recognize a continuity between beings that runs deeper than our day-to-day separation from one another: we recognize the inevitability of a state in which we cease to exist as bounded and autonomous selves.

By a similar token, Bataille identifies in lovers the impulse to dissolve into one another, to fuse and in doing so destroy – at least temporarily – the discontinuous subjects that existed before the moment of sexual union. It is therefore unsurprising, says Bataille, that Sade should find death and eros so close together as to be effectively identical.

Bataille writes about these moments of continuity extensively in his fiction, particularly in his novella Story of the Eye (1928). The book’s most famous scenes occur as the narrator and his companion, Simone, watch bullfights in Spain, and become aroused first at the sight of the bulls’ disemboweling horses, and then even more so as the bull gores the matador, dislodging one of his eyes (one of the eyes to which the story’s title refers).

Much like observing a religious sacrifice, Bataille presents the narrator and Simone as experiencing a moment of sudden continuity in observing the moment of death and destruction. The continuity we recognize in death, Bataille suggests, is the logical conclusion of the lover’s and the believer’s desire for continuity. Death constitutes the final relinquishment of the discontinuous, conscious self: the condition that eroticism tends towards. Bataille writes:

“De Sade–or his ideas-generally horrifies even those who affect to admire him and have not realized through their own experience this tormenting fact: the urge towards love, pushed to its limit, is an urge toward death. This link ought not to sound paradoxical.”

Bataille, Erotism (1957)

Limit Experiences

It is not, however, just the pursuit of continuity that bundles together sex, death, and religion. After all, this impulse does not by itself explain the preoccupation – in both Sade and Bataille’s own writing – with cruelty, violence, and torture. There is also a sensory similarity between these cases: an extremity of experience in which suffering, ecstasy, and encounters with the divine become indistinguishable from one another.

If we return to the image of Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa, we see a moment of religious ecstasy which looks unmistakably like the face of someone caught in the throes of passion. The sculpture captures a kinship between these experiences, one conventionally deemed sacred, the other profane. Divine revelation here, as in many biblical passages (and even more so in later writings on mysticism), is presented as pushing the very boundaries of sense and experience, as overwhelming Teresa to the point of collapse. Teresa’s sculpted face is not only hovering between awe and orgasm, its parted lips and drooping eyelids could also be capturing the moment of death.

These ‘limit experiences’, as Michel Foucault theorized them in relation to Bataille’s thought, are experiences in which we approach states of impossibility: states of frenzy and ecstasy where life and conscious subjectivity temporarily dissipate, moments at once terrifying and blissful. Limit experiences push sensation and thought beyond the point where the person experiencing it can still say ‘it is me, a thinking and feeling individual, who is experiencing this’.

The suffering in Sade’s writing is merely asserted as being proximate, or conducive, to pleasure. In Bataille, it is theoretically relocated to the world of sacred things of things that live outside our ordinary lives. It is hard to tell, however, whether Bataille thinks suffering and physical pain are able to produce limit experiences because they always imply, or tend towards, the ultimate discontinuity of death, or simply because of their intensity, their tendency to overwhelm the conscious mind.

Georges Bataille’s Erotism and its Connection to Death, Reproduction, and Waste

Bataille’s ideas about the sacred and profane also connect to his political interest in the interrelation of usefulness and waste. While the world of discontinuous selves is one of usefulness and calculated self-interest, the sacred realm is inclined to grandiose excess: the expenditure of resources without consideration for their utility or recuperation. While Bataille’s ideas on wasteful expenditure are more completely laid out and explored in his work of political economy, The Accursed Share (1949), the motif of wanton expenditure is also important to the thesis of Erotism.

Sacrifice and non-reproductive sex fit into this model relatively obviously, as each involves an outlay of energy or resources. In Story of the Eye, the narrator and Simone dedicate their every waking hour to the cultivation of more and more extreme erotic pleasures. Gone from these practices are anxious musings about whether a given use of time or resources is worth it, and gone are considerations of personal gain, of the kind that regulate ordinary economic exchanges and labour. In the case of death, Bataille explains more thoroughly the notion of waste:

“A more extravagant procedure [than death] cannot be imagined. In one way life is possible, it could easily be maintained, without this colossal waste, this squandering annihilation at which imagination boggles. Compared with that of the infusoria, the mammalian organism is a gulf that swallows vast quantities of energy.”

Bataille, Erotism

Bataille then contends that our hesitance about waste, about inutile expenditure, is a definitively human anxiety:

“The wish to produce at cut prices is niggardly and human. Humanity keeps to the narrow capitalist principle, that of the company director, that of the private individual who sells in order to rake in the accumulated credits in the long run (for raked in somehow they always are).”

Bataille, Erotism

Death then – contemplating it, watching it, approaching through sex and sacrifice and suffering – is an escape from the narrowness of human concerns, and from the decidedly individual perspective that obsesses over usefulness and profitable investment. In embracing the wastefulness of death, Bataille suggests, we draw closer to the limits of our discontinuous selves, closer to bridging the gulf between minds. It is in this way that Bataille solves what he calls the ‘great paradox’: the essential sameness of eroticism and death.