The First World War is primarily remembered for its gruesome battles and heavy trench warfare in Europe. In the west, the muddy fields of Belgium and France hosted the intense slaughters etched in the memories of those who fought, while in the east, the Russians paid a heavy price in their war with the Germans and Austro-Hungarians.

Meanwhile, far away from these cold and wet trenches were the hot and dusty plains, thick grasslands, and forests of East Africa, where the Germans fought against the British and all their allies. The East Africa Campaign was a very different kind of war, but one that deserves historical recognition.

Mittelafrika

Before and during the First World War, the Germans had plans to link up the four German territories in Africa to create the proposed Deutsche Mittelafrika (German Central Africa). German East Africa was the foundation from which this plan could be enacted, for it was there that the Germans were the most powerful.

Despite the Maji Maji Rebellion from 1905 to 1907, German control remained firm. Tens of thousands had risen up against German colonial rule when the Germans tried to force them to grow cotton for export. With a force of just a few thousand, which comprised trained Schutztruppe (protection troops), numbering just 260 soldiers, 2,700 European settlers, and 2,470 Africans.

It is estimated that the rebellion forces were in the region of 90,000 combatants. Despite this massive numerical advantage, the German colonial forces were victorious and pursued their control using starvation, resulting in genocide.

Colonial militaries across the continent were weak and used obsolete weapons. They were intended to be paramilitary forces rather than frontline soldiers, so the effort to fight an effective campaign was dogged on both sides from the outset. In Britain’s favor, however, was a bigger colonial empire with more resources to draw from. Of note was the contribution of South African forces. Experienced and battle-hardened, these soldiers were comparatively well-equipped and effective.

While South Africa was essentially independent at this point, the decision was made to take sides against the Germans.

Two years before the First World War began, the Germans had a plan in place. General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck, in charge of the German forces, would threaten the British Uganda railway and force the British to divert valuable resources from Europe to Africa. From this point, the Germans would withdraw and prepare to fight a guerilla war, grinding down the British in the thick African terrain.

The War Begins

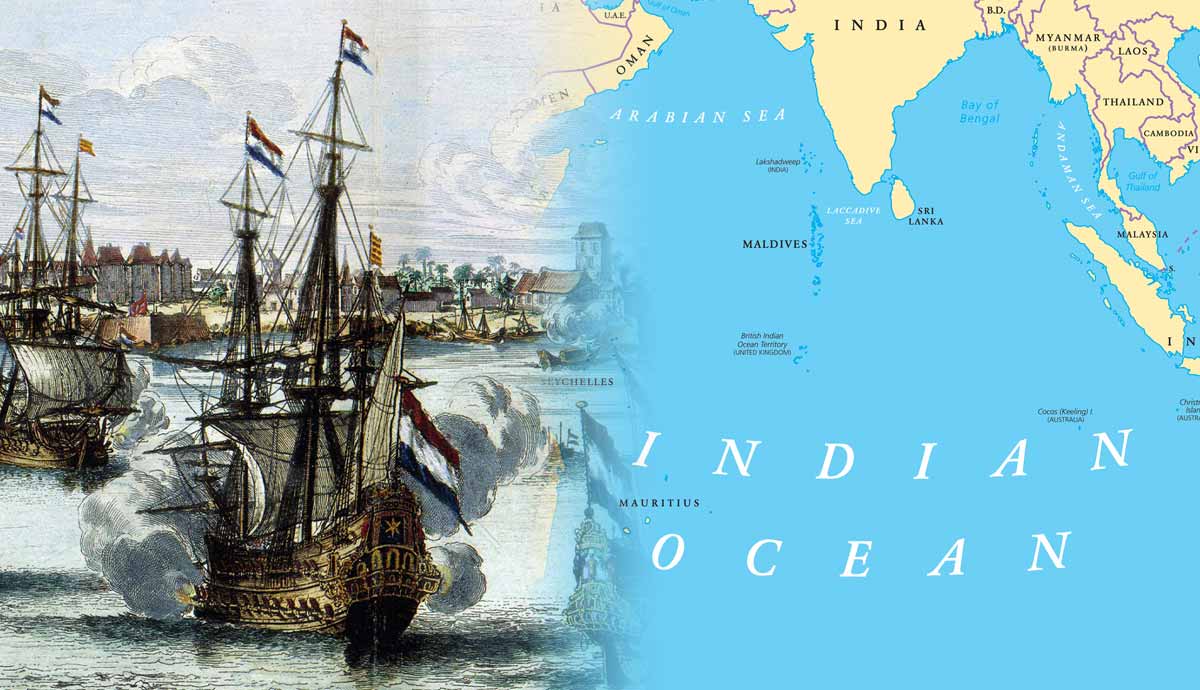

On July 31, three days after the war began in Europe, the German cruiser SMS Königsberg sailed from its port in Dar-es-Salaam with the intention of attacking British commerce in the Indian Ocean, narrowly avoiding two cruisers from the Cape Squadron, which had been ordered to shadow the German ship.

Once the way was open, the HMS Astraea sailed towards Dar-es-Salaam and opened fire on the city. This resulted in a ceasefire agreement.

The Germans and the British started mobilizing ground forces. The British sent an expeditionary force, bolstering their regional forces to between 12,000 and 20,000 troops, with heavy support from the King’s African Rifles, the forces made up of local Africans. The Germans had their own version of this local force, but both sides referred to native African soldiers as Askaris.

On November 3, the British Expeditionary Force launched an attack with 4,000 British Empire troops in an attempt to capture German East Africa quickly. With reinforcements over the coming hours and days, the size of this force swelled to 9,000 troops. Opposing them, the German forces numbered just 1,000.

Because of the ceasefire, the Royal Navy, with knowledge of British plans, felt it dishonorable not to warn the Germans of the British intentions. With this development, the element of surprise was lost. Nevertheless, the British started the assault on the city of Tanga on the coast while another 1,500 troops to the northeast pushed southward to the town of Longido to the east of Mount Kilimanjaro.

This two-pronged attack was an abject failure. Despite being outnumbered with an average of eight to one at Tanga and four to one at Longido, the Germans prevailed at both points. These two battles became known as the Battle of Tanga and the Battle of Kilimanjaro, respectively.

Meanwhile, off the coast, the naval Battle of Zanzibar began. The Königsberg managed to sink an old British cruiser, the HMS Pegasus, but the Königsberg was cornered by the Cape Squadron and attempted to escape towards the Rufiji River, where it was sunk. The Germans managed to salvage the main battery guns of the Königsberg and were able to use them in the years to come.

Tanganyika

1915 was a relatively quiet year for ground forces in East Africa, with no major battles being fought. The Germans were heavily outnumbered and relied on guerilla-style actions to keep their enemy occupied. In the water, however, the British achieved an incredible feat.

The Germans controlled Lake Tanganyika with three steamers and two unarmed motorboats. Challenging the notions of what was actually possible, the British hauled two motorboats 3,000 miles to the shores of Lake Tanganyika where they were launched to take the fight to the Germans. The HMS Mimi and the HMS Toutou captured the German steamer SMS Kingani and re-christened it the HMS Fifi.

The Belgians then joined in the action, aiding the British with two ships of their own. The SMS Hedwig von Wissmann was cornered and sunk, while the unarmed motorboat SMS Wami was run aground. The last German ship, the SMS Graf von Götzen, was scuttled later that year. It was later re-floated and now serves as a ferry, run by the Marine Services Company Limited of Tanzania under the name the MV Liemba. It is the only ship of the German Imperial Navy still sailing today.

Bigger Battles

For the first year and a half of the war, forces were being built up. A quick end to the fighting in Europe did not emerge, nor did it emerge in East Africa. In 1916, General Horace Smith-Dorrien was assigned the task of commanding the Allied troops and leading a new campaign against the Germans. On the way to Cape Town, South Africa, however, he developed pneumonia and had to be replaced.

South African general Jan Smuts took over. He had fought against the British in the Second Anglo-Boer War and was well versed in the ways of guerilla warfare, a style which he now had to face from the enemy. His experience made him well-suited for the job.

The initial forces assigned to the campaign were mostly South African Boers, British, Rhodesians, Indian, and African troops, with a large contingent of logistics and supply troops. In total, about 73,000 troops were mustered, with 13,000 of them being combat-capable. In addition, hundreds of thousands of Africans were conscripted to serve as porters. These numbers increased throughout the conflict to the point where, by the end of the war, around 90 percent of the Allied force was made up of native Africans.

Although the campaign was considered an operation under the flag of the British Empire, it developed into what was essentially a South African-controlled initiative.

The Allied forces invaded German East Africa from several directions, including the Belgians, who invaded from the west. Von Lettow-Vorbeck pulled his forces back quickly and gave ground to the vastly superior numbers facing him. He evaded capture while his troops continued their guerilla war.

Mired in terrible conditions, the Allied forces began to take heavy casualties as disease set in, felling tens of thousands of troops. General Smuts could not stay to resolve the situation, as he was called to serve in the Imperial War Cabinet in London. The forces in Africa found themselves briefly under the command of Major-General Arthur Hoskins of the King’s African Rifles, who was replaced four months later by South African Major-General Sir Jacob Louis van Deventer.

Meanwhile, the Belgian forces captured the territories of Rwanda and Burundi and pressed further into German East Africa, defeating the Germans at the Battle of Tambora. This critical action left the railroad Tanganjikabahn under the control of the British and Belgian forces and proved a significant logistical asset.

Major-General Jacob van Deventer began a renewed offensive in July 1917, pushing the Germans back another 100 miles south. The offensive was halted in October when the Germans, outnumbered two to one, managed to defeat the Allied forces at the Battle of Mahiwa. The Allies were forced to withdraw, but despite the German victory, the Germans were also forced to abandon their defensive positions due to unsustainable losses.

With dwindling supplies, the Germans turned their attention to plundering Portuguese assets in colonial Mozambique. Before reaching Mozambique, however, a section of 1,000 German troops were forced to surrender after running out of food. Despite this major blow, the rest of the German forces carried on, marching through Mozambique.

They defeated the Portuguese at the Battle of Ngomano and spent the next few months on the march, pillaging Mozambique for supplies, but they failed to gain the necessary strength to get back into the fight with the Allies to the north.

Surrender & Death Toll

Running dangerously low on ammunition, the Germans learned of a cache of supplies in a warehouse in Northern Rhodesia. They began probing attacks on November 12 and captured a British dispatch rider who informed them of the Armistice signed the day before. Stunned by this information, Von Lettow-Vorbeck struggled to understand how Germany had lost the war. He nevertheless called off the attack. Two weeks later, he offered his surrender.

The war was over.

In military terms, the campaign in East Africa was much smaller than the operations in Europe. Although it took place over a much bigger area, there were comparatively few soldier deaths.

The British, Belgians, and Portuguese lost somewhere in the region of 20,000 soldiers killed, while the Germans lost just over 2,000. The real devastation, however, was the effect on the local conscripts and civilians. Over 100,000 porters died in the service of the Allied forces, while 7,000 died in the service of the Germans.

Civilian casualties were the worst. An estimated total of 365,000 Africans lost their lives to famines brought about by the war. With so many conscripted porters, there was nobody left to tend the farms.

The lack of food ended up affecting the Allies and the German rationed troops as well, and with only rudimentary medical supplies in most cases, malaria and sleeping sickness took their toll, along with other more common diseases such as dysentery.

Aftermath of the East African Campaign

The aftermath of the East Africa Campaign signified a shift in thinking for many Africans. European weaknesses became evident, and the idea that the Europeans were somehow superior faded away. This gave rise to an increasing anti-colonial and nationalistic sentiment that would foment rebellions in many of Africa’s colonies.

With the defeat of Germany, the Second Reich’s imperial ambitions were scuppered, and its African colonies were divided between South Africa and European colonial powers.

For military historians, there is much to digest in studying the armies and the battles of the East Africa Campaign.

For many others, the campaign in East Africa was just another example of colonial forces throwing away the lives of Africans in a dynamic that had lasted for centuries. Perhaps it was this monumental death toll that is far more important than whether the campaign was a victory or loss for any of the European powers or even the South Africans who imposed colonial mores on the African majority for decades to come.