This bold claim of status and self-promotion was first declared in an issue of a local journal, the “East Liverpool Tribune”, in its edition of March 22nd, 1879. The Tribune regularly featured reports on the local industry in its coverage, and this published article focused on the East Liverpool potteries.

Their claim was that the town, had by then earned a reputation as the “Ceramic City, the Staffordshire of America.” There was, in fact, a strong element of truth in this statement and the centers of pottery production in that area had definite connections to the English Potteries.

The Glory Days of Ohio River Valley Pottery

There was a localized area of small-scale manufacturing that developed in townships along the Ohio River in the States of West Virginia, Ohio and in Pennsylvania and Vermont, during the early nineteenth century. The main center of production was East Liverpool, in Columbiana County, Ohio and pottery were first set up there in 1839 by an immigrant potter from North Staffordshire, James Bennet. A number of kilns were quickly set up locally and by 1843 an ambitious Bennett was confident enough to send a circular letter back to his home country, encouraging all workers who could to come and join the new works. James declared that although the pottery industry in America had just made a start, it was possible to make wares in East Liverpool as good as any made in England.

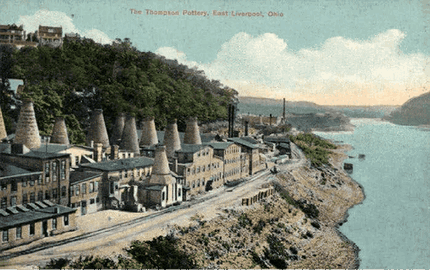

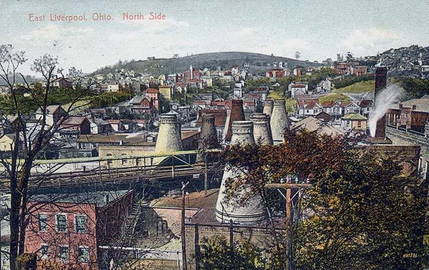

Many small single kiln factories were soon set up and the call for labour was met by poverty-stricken workers from the English Midlands who were shipped out to America and who hoped to use their skills to establish themselves and find prosperity and independence. Pottery factories sprang up all along the Ohio River, and this growth spread across the river into Chester and Newell in West Virginia. The region became intensively developed, producing finished goods that would be transported by river to reach the East Coast and the Great Lakes area.

RECOMMENDED ARTICLE:

Aegean Civilizations, the emergence of European Art

Economic Migration

The key to this “New World” development was, in fact, the very serious situation existing in The North Staffordshire Potteries of England in 1842. In the summer of that year there was a bitter local coal miners dispute, with colliers locked out of the pits for several weeks by unscrupulous owners who were seeking to impose reductions in wages. Many of the “Pot Banks”, dependent upon coal for firing, were left idle without production. Unrest grew in Stoke on Trent with many families unemployed and close to starvation. Because of this situation, “New World Fever” developed and an escape to America gave the promise of a way out for hundreds of Stoke workers.

Local reformers in Staffordshire were encouraged to fund Emigration Societies to help workers, and the exodus of skilled miners and potters was significant. This was an effective form of nineteenth-century social engineering, as each emigration of an unemployed trade worker to America, helped to enhance the market value and wages of those left behind. Local industries in both countries then benefited.

By the 1880’s East Liverpool had developed into a town of about 13,000 inhabitants, and around 200 pottery factories were operating there, with perhaps 30 of these being significant. This centre soon surpassed its main Eastern rival, Trenton, New Jersey, in importance and with this success the area earned itself the popular title of “The Pottery Capital of the World.” Then, around half of North American production of ceramics was from the region.

British Heritage. A Proud Tradition.

East Liverpool was helped in its development by its location on a major river and by the skill and enthusiasm of its workers. The key resource, clay for potting, was locally yellowish in colour and resulted in the primary production of ubiquitous “yellow wares”, although other pottery forms were developed, such as a regional variation of so-called “Rockingham” ware, based on a popular ceramic form first seen in South Yorkshire, England.

The English form of Rockingham was developed in Rotherham in the mid-nineteenth century and was characterized by ornate forms of earthenware with a thick brown glaze. The Yorkshire Pottery operated under the patronage of the Marquess of Rockingham, and the family gave its name to the popular brown glazed ceramic form. “Rockingham Ware” became much imitated, even in America where it was produced at several factories. The most notable of these was at Bennington, Vermont while in East Liverpool the main producer of Rockingham style ware was Jabez Vodray. Many examples of Rockingham work can be found in the East Liverpool Museum of Ceramics.

Whitewares were produced from better quality clays imported mainly from Pennsylvania and New Jersey, and by about 1880 several American firms, including Knowles, Taylor and Knowles and also Homer Laughlin & Co, began to make white “graniteware” in imitation of Staffordshire goods, although many of the American ironstone wares had simpler shapes than the English versions.

The peak years of production for the Ohio River potteries probably ended by about 1900 and the industry had certainly declined by about 1930. But a legacy remained, with a small number of companies meriting the attention of Collectors.

The Key Producers

Bennington pieces probably attract the most attention nowadays as the wares produced were mainly decorative with aesthetic appeal. The United States Pottery of Bennington was founded by Christopher Fenton in 1840 and was active throughout the nineteenth century. The Norton family, chiefly making Stonewares, was also important in the area.

Several names that have historic connections to the area retain interest. One such factory is the productive “Mansion House,” a maker of both Yellow and Rockingham, established by Salt and Mears, and so named as it was originally set up in a converted residential property.

One main firm, the Hall China Co, first set up in 1903 survives and the Homer Laughlin China Co, opened in E Liverpool in 1874, still exists across the Ohio River, in Newell, West Virginia, where it moved in 1907. Other major names are known, including American Limoges; Standard; Thompson; Fawcett and also Knowles, Taylor & Knowles.

James Bennett, the industry pioneer, had mixed fortunes. After he started his pottery in 1839, he worked on different body shapes and materials and his three brothers in England, then joined him in the firm of Bennett and Brothers. The pottery moved to Birmingham, near Pittsburgh in 1844 and his factory was taken over by Thomas Croxall running until 1898.

Other eminent East Liverpool names from around 1900, were the Novelty Pottery, (later McNicol), the Broadway Pottery and Goodwin Brothers. The Harker Pottery was making Yellow wares and Rockingham until 1879 and then white graniteware going into the 1900’s.

Identifiers And Base Marks

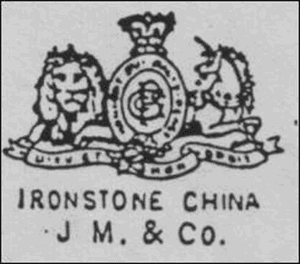

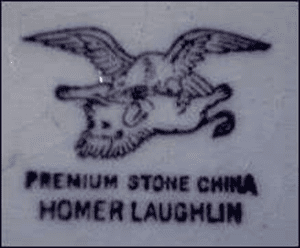

Initially, American potteries did not mark their wares or used interpretations of British Royal Arms to help sell their goods. It was not until about 1870 that quality improved and people felt more confident enough about buying American goods. There was then a transition from the use of a British Coat of Arms to the American Eagle, and the origin of goods became more readily identifiable.

Here are both an early and later different mark from one factory, John Moses and Co, of the Glasgow Pottery,

One of the bigger Pottery makers, Homer Laughlin, went one better and used a motif of an American Eagle attacking a British Lion!

Ohio River antique pottery must be regarded as an area of specialist interest and gains the most attention today when traded online. Most inquiries for good examples come from the United States but there is UK appeal, as many enthusiasts appreciate a point of reference for the English pottery industry’s influence abroad. This is a niche collectible focus.