Giacomo Balla was equally innovative and controversial. He was a vital member of the Italian Futurist movement. Balla’s lifelong preoccupation with light, dynamism, and movement made him one of the most prominent artists of the twentieth century. At the same time, his political alliances left an uneasy mark on his oeuvre. Continue reading to learn more about Giacomo Balla and his fascinating artistic career.

1. Giacomo Balla Started as a Neo-Impressionist

Giacomo Balla was born in 1871 in Turin, Italy. He did not want to become a painter in his early years, but his parents’ plan wanted him to become a musician. However, a tragic incident turned his life in a different direction. After losing his father at the age of nine, Balla had to quit his music studies. He started working as an apprentice in a lithography shop to support his family. At that moment, the artist Giacomo Balla was born. He taught himself to draw well enough to be accepted to an art academy, move to Rome and make a decent living as a caricaturist and portrait painter.

Originally, Balla started as a proponent of Divisionism, a Neo-Impressionist art movement founded by Georges Seurat in the 1880s. Divisionism relied on optical effects like small dots of primary colors carefully arranged on canvases, creating vivid multicolored compositions as if gently touched by sunlight. Despite the fact that Balla soon moved further in his artistic alliances, his interest in light and optical effects persisted throughout his entire life. The painting Girl Running on a Balcony demonstrated a combination of the Divisionist technique of applying small patches of color with the Futurist depiction of various stages of movement at once. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Balla combined his artistic practice with teaching Neo-Impressionist techniques. Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini, who would soon become his artistic brothers in arms, were among his students.

2. Light and Movement Were His Primary Preoccupations

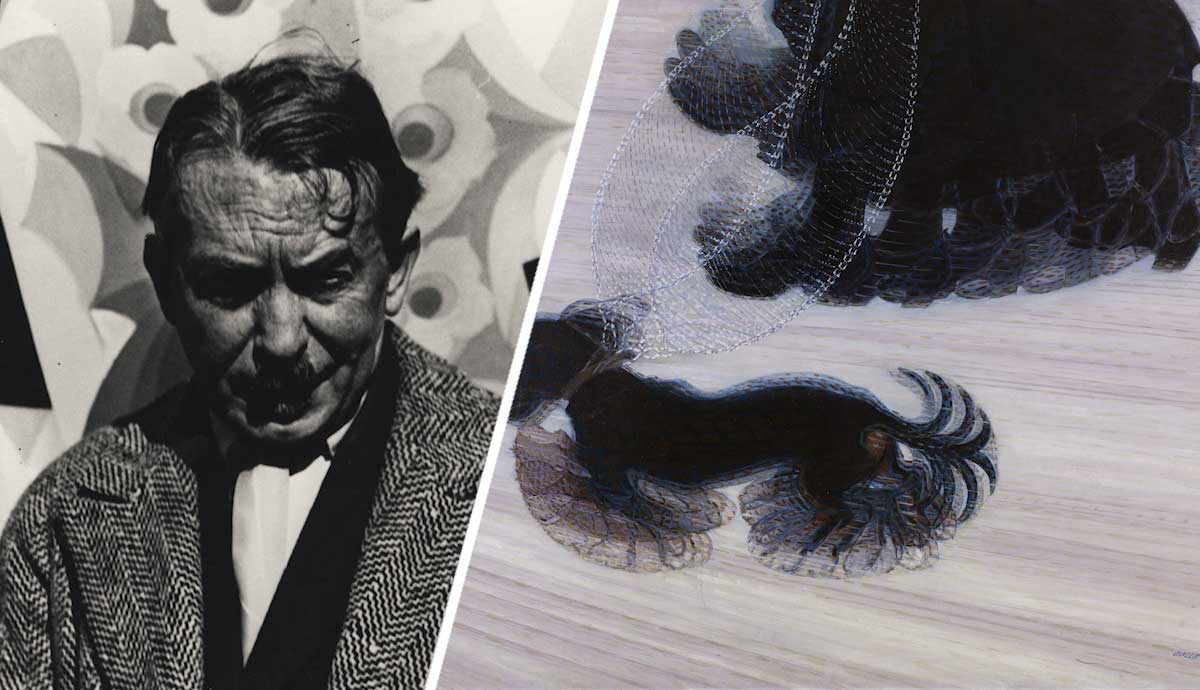

Although Balla did not receive any artistic training in his early years, his father owned a photography studio where the boy witnessed a newborn miracle of moving objects fixed in static on a photographic plate. The foundations of his later preoccupation with movement could be traced back to those moments. Balla’s most famous work Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash is an obvious nod to chronophotography, an earlier technique of capturing several stages of movement of subsequently made photographs. In Balla’s painting, a tiny dachshund is pacing the pavement, the number of its wobbling ears and paws radically exceeding their regular quantity. By painting dozens of legs, tails, and leashes, Balla managed to convey a feverish movement of a short-legged creature struggling to keep up with its owner.

Balla’s interest in light, movement, and optical effects was profound but far from unique. In the late nineteenth century, many artists, starting with the Impressionists, found their inspiration in treatises on physics and ophthalmology. The groundbreaking knowledge of the structure and mechanisms of the human eye and its perception provided progressive young artists with new methods and theories.

3. Balla Was a Key Member of the Futurist Movement

The new artistic movement called Futurism was on the rise in Italy under the guidance of a charismatic poet named Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti praised the new age of technology and machinery, demanding the destruction of all remnants of the past, including museums and libraries. Such a radical claim could be explained easily by looking at the state of affairs in Italy in the early twentieth century. Being a poor and undeveloped country compared to other European states, Italy was mostly known for its cultural heritage and ancient ruins scattered all over the country. The young generation, which included the Futurists, was tired of ancient culture defining the present and was looking for new ways to express its national identity.

It is unclear if Balla was the one who influenced his students or if it were young Boccioni and Severini who were sharing fresh and radical thoughts with their teacher. However, in 1909, the three of them signed the Manifesto of Futurism, which Marinetti wrote. The Futurist demand to destroy everything old in order to give way to the new future was not limited to burning down galleries and academies. They glorified wars as the world’s only hygiene and were aggressively militaristic in their claims.

4. He Became Mussolini’s Supporter

After declaring himself a Futurist, Balla staged an artistic death of his old self. In 1913, he hung a banner on the facade of an antique shop in Rome that read Balla is dead, here are sold works of the late Balla. Despite this public claim, Balla kept several of his old paintings with him. Balla stopped signing his works with his full name, opting for the pseudonym Futurballa instead.

The artist was the oldest and most respected of the Futurists. The rise of the new artistic movement coincided with the Italian political course changing radically. As Benito Mussolini came to power and the fascist regime started to unfold, the Futurists became his avid supporters. Nationalism and militarism were now part of the official ideology, and Futurism strived to occupy the place of the official art movement. However, despite keeping relatively close contact with Balla and Marinetti, Mussolini had little interest in choosing one particular style over countless others.

5. Balla Designed Menswear

Giacomo Balla’s Futurist explorations were not limited to visual arts only. He also planned to revolutionize the ways in which Italians dressed. He started making Futurist clothing and promoting the new style to fit the new era. Although Balla stuck to simple cuts of suits and vests, his innovation was present in the details. Instead of conservative monochrome greys, blacks, and browns, his Futurist clothing showed geometrical patterns of contrasting colors. Balla called it an anti-neutral dress and insisted that the new, colorful clothing perfectly matched the new dynamic cities and the new industrial world. In a way, he was also a proponent of what we now know as fast fashion. In his Futurist Manifesto of Menswear, he wrote that clothing should not last very long in order to keep a sense of novelty and enjoyment for the wearer.

In his Futurist Manifesto of Menswear, he also wrote:

We are fighting against:

(a) the timidity and symmetry of colors, colors which are arranged in wishy-washy patterns of idiotic spots and stripes;

(b) all forms of lifeless attire which make a man feel tired, depressed, miserable, and sad, and which restrict movement producing a triste wanness;

(c) so-called ‘good taste’ and harmony, which weaken the soul and take the spring out of the step.

6. He Designed A Futurist Apartment

Balla did not only preach his aesthetic revolution. He lived by it. He designed a truly Futurist home for his family. The apartment named Casa Balla, perhaps the artist’s most ambitious work, was painted with the brightest colors and boldest of patterns possible. Balla also designed furniture and household objects to make the space not only visually pleasing but utilitarian too. The artist’s daughters, Elica and Luce Balla, were also involved in the design process. They made tapestries and textile objects for their home.

Balla and his family lived there until the 1990s when the artist’s daughters passed away. After renovation, Casa Balla was finally opened to the public in 2021. The opening coincided with the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth.

7. Balla Left His Futurist Legacy Behind

Despite Balla’s cult status in the 1930s, the artist gradually grew cold towards his Futurist beliefs and his younger colleagues. In 1937 he published an open letter in an Italian newspaper, stating that he no longer wished to be associated with the movement. He declared that Futurism was now made by soulless opportunists who cared more about making money than making art. His concern was that the Futurist style mutated into simple ornamentation rather than an accurate depiction of objective reality.

Balla declared that absolute realism was now the purest form of art, desperately needed by the world. After publishing the letter, he completely switched to realism.

8. The Lasting Legacy of Giacomo Balla

Balla had a profound interest in speed and movement, but he avoided painting intimidating roaring mechanisms and scenes of mechanical violence. He preferred to address more mundane objects found in everyday life on a regular street. Today, Giacomo Balla is considered to be one of the most influential Italian artists ever, with his works influencing generations of younger artists. Every now and then, aspiring clothing designers and big couture houses use his designs to reinvent fashion once again, following Balla’s call to attack the dull greyness of everyday life with color, light, and form.