Giorgio Agamben is one of the most influential living philosophers. This Italian thinker holds a deep fascination for Dante’s Divine Comedy, going so far as to theorize about it. Agamben poses the following questions: why did Dante decide to call the Divine Comedy a comedy? What did such a decision say about medieval culture, and what implications has it had for those who followed Dante? This article follows Agamben’s problematization of the interpretation of the Divine Comedy. It then discusses the relationship between the dichotomy of tragic and comic guilt on the one hand with natural and personal guilt on the other. It concludes where Agamben does – with an analysis of these dichotomies as the ‘secret thoughts’ of Italian and Western culture.

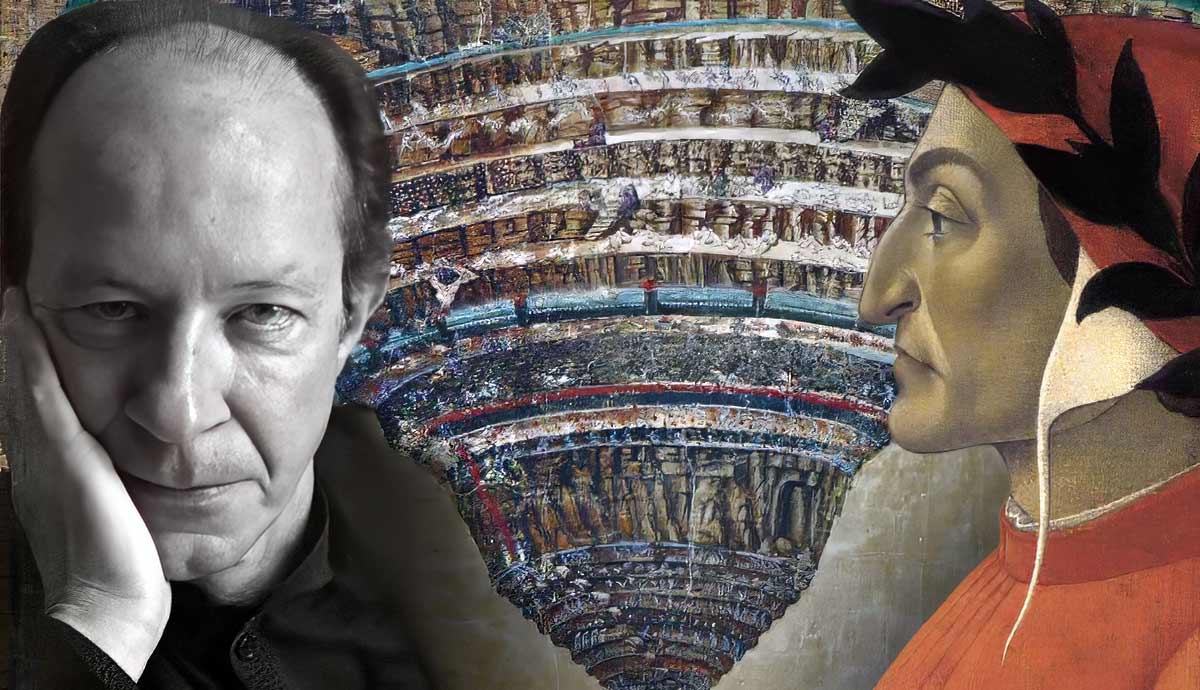

The Biographical Context: Giorgio Agamben and Dante Alighieri

Before discussing Agamben’s essay, some biographical context is necessary. Giorgio Agamben is a contemporary philosopher with a long-running interest in poetics, whose broad intellectual interests are matched by a genuine originality of style and thought. The collection of which this essay is a part was, on his own account, borne from an earlier, abandoned research project in which he and several of his friends intended to attempt to identify the defining conceptual binaries of Italian culture.

One of the binaries which Agamben says he suggested was that of “comedy/tragedy.” Of all of the essays collected together as The End of the Poem, it is this one which is most faithful to this original project. It can be circumscribed within the procedure Agamben articulates thus: “Each of the essays in this book thus seeks to define a general problem of poetics with respect to an exemplary case in the history of literature.”

Who was Dante? Dante Alighieri was a Florentine poet of the late 13th and early 14th centuries. His life was marred by the bloody conflicts which gripped his native city of Florence, as they did much of Italy. He is inarguably the most famous poet who wrote in the Italian language. Indeed, one of his most significant achievements was his defense of literary writing in said language, which people at the time actually spoke, rather than Latin. His most significant achievement was undoubtedly his ‘Divine Comedy’ (which he simply called the Comedy – the word “divine” was added by readers of subsequent centuries). A work in three parts, it follows Dante himself as he is led by his guide, the Roman poet Virgil, through hell, then purgatory, and then on to paradise. The first section of his journey, called “Inferno,” is one of the most famous books of poetry ever written.

Why is the Divine Comedy Called a “Comedy”?

Agamben’s discussion of comedy and tragedy begins with what seems to be a simple interpretative question about Dante’s work. The question is this: why did Dante label his work a “comedy”?

This apparently simple question is immediately thrown into disarray by Agamben’s claim that it has been subjected to repeated misinterpretation, almost for as long as there have been critical responses to the Divine Comedy. At the same time, the stakes are raised:

“it can even be said that here, for the first time, we find one of the traits that most tenaciously characterizes Italian culture: its essential pertinence to the comic sphere and consequent refutation of tragedy.”

Agamben claims that one of the definitive dualities of Italian culture is born at the very moment when Dante labels his poem a comedy. Agamben argues that attempts to offer conservative answers to this question — those which claim it was natural and expected that Dante would label the Divine Comedy a comedy — are insufficient. This kind of response finds its origins in Boccaccio, who claimed that,

“…the entirety of comedy is this: comedy has a turbulent principle, is full of noise and discord, and ends finally in peace and tranquillity. The present book altogether conforms to this model.”

No Easy Answers

Problems abound with this Bocaccio’s attempt to explain away Dante’s title. For one thing, it runs against the conception (taken up both by Dante and others) of tragedy as a marker of style, not just narrative structure. For another, Dante’s own conception of what tragedy is appears to change throughout his life – in earlier writings, he claims that the highest form of poetry is tragic.

It would serve us to clearly distinguish, as Agamben does, between the material-substantive definition of the tragedy/comedy dichotomy, and the stylistic-formal definition. The material-substantive definition, in the spirit of Boccaccio’s, has comedy as a foul beginning culminating in a pleasant end, and for tragedy, roughly vice-versa. The stylistic-formal definition is less clear-cut: it states that the tragic poem is written in the “high” style (this does not mean, for instance, that it is necessarily written in Latin as opposed to the vernacular).

Regardless, we can say with some certainty that Dante wrote the Comedy as a poem in the highest style, and yet it follows the material-substantive pattern of a comedy. In other words, there is a contradiction between these two ways of characterizing the comedy/tragedy dichotomy. Therefore, it remains to be explained why he would label his “sacred poem,” his greatest work, as a comedy after all. “For Dante, the comic title of his poem is neither contingent nor fragmentary, but rather constitutes the affirmation of a principle.”

Guilt and Christianity

What is the principle that Dante is affirming through his work? What, for that matter, is a principle in this context? The point of contrasting the affirmation of a principle with either the formal-stylistic definition of the tragedy-comedy dichotomy or the material-substantive definition is that the former constitutes an attempt to go beyond the structure of the poem and make judgments that we might consider philosophical. The reach of these judgments is, indeed, all the way down (or up). As per Agamben:

“The “prosperous” or “foul” ending, whether comic or tragic, therefore acquires its true meaning only when referred to its “subject”: it thus concerns man’s salvation or damnation… Far from representing an insignificant and arbitrary choice on the basis of vacuous lexicographic stereotypes, the comic title instead implies the poet’s position with respect to an essential question: the guilt or innocence of man before divine justice.”

Yet the problem presented here is not simply whether man is guilty or innocent according to Christian dogma. Rather, it is a question of kind: if man is guilty, how is he guilty? If he is innocent, how is he innocent?

Tragic Guilt and Comic Guilt

The tragic and the comic represent two different kinds of guilt. Tragic guilt is natural guilt. Comic guilt is personal guilt. This distinction is supported by a concept of Christian theology, that of original sin. What is original sin? Original sin is the guilt that human beings inherit simply by virtue of being human, and it can be traced back to the treachery of Adam and Eve against God in the Garden of Eden.

St Paul’s Epistle to the Romans is often taken as the most orthodox statement of the doctrine of original sin: “Therefore, just as sin entered the world through one man, and death through sin, and in this way death came to all people, because all sinned.”

The earliest Christian theologians saw original sin as central to our conception of human nature. And yet the force of original sin is taken to be radically altered by Christ’s existence. As Agamben puts it,

“It is this dark “tragic” background that Christ’s passion radically alters. Adequate to the guilt that man would never have been able to expiate, the passion carries out an inversion of the categories of person and nature, transforming natural guilt into personal expiation and an irreconcilable objective conflict into a personal matter.”

If tragic guilt is natural guilt, and comic guilt is personal guilt, then Agamben thinks that we must recognize that Christ’s passion effects a movement from tragic inevitability to comic possibility.

Giorgio Agamben’s Answer to the Interpretative Mystery of the Divine Comedy

What happened, then, when Dante called his poem a Comedy? Agamben says that this is the answer:

“A Florentine poet decided to abandon the tragic claim to personal innocence in the name of the creature’s natural innocence, leaving behind perfect Edenic love for the sake of comically divided human love.”

This constitutes the “anti-tragic inheritance” left by late-medieval culture for the people who came after. Agamben does not see the modern world as the world made by Dante, but rather as the world Dante rebelled against in vain. The tragic picture of the world would, in Agamben’s view, come to be reasserted by our awareness of the “tragic character of history” (Agamben does not say, but might well have said, of history and of human nature).

It is in this sense that Agamben believes Dante speaks aloud one of our culture’s “secret thoughts” – it is a moment of rebellion, of flight from the normal structure of Western literary, political, and social organization. That is the importance of the Comedy’s title.