Has something fundamentally changed in terms of how the modern state operates? If so, what is it? The relationship between modernity and contemporary politics has been a provocation for a vast array of philosophers and theorists for at least a hundred years.

This article focuses on Giorgio Agamben’s attempt to address this relationship by analyzing some of the concepts with which he attempts to make sense of it. It begins with a discussion of the relationship between Michel Foucault’s work and Agamben’s. It then moves on to a discussion of biopolitics and the state of exception, before concluding with a discussion of the relationship between biological life, political life, and bare life.

Giorgio Agamben and Michel Foucault

Giorgio Agamben is best known as a political theorist, but elements of his theorization of politics have proven to be influential far beyond politics as such. Indeed, some of the concepts discussed in this article have been put to use in almost every area of the humanities. It is worth bearing Agamben’s exceptional influence in mind whilst reading, and attempting to work out for oneself just what made this way of thinking about contemporary politics so plausible to academics working in such an array of fields.

There is much in Agamben’s political thought which is difficult to explain without a brief discussion of Michel Foucault, the French theorist and historian, whose work Agamben was simultaneously inspired by and critical of. In particular, Agamben’s political theory is concerned with a reanalysis of the Foucauldian concept of biopower.

The concept of biopower is the realization of a historical claim: that whereas throughout most of human history, human beings had a political existence which in some sense separable from the rest of their lives, modern life is characterized by the inseparability of life and politics. Foucault distinguishes the previous form of political power as “sovereign power” (which is characterized as the extension of power over death and “killing or letting live”) from biopower, which is the extension of power further, into the realm of producing and governing life (“fostering life or disallowing it”).

Agamben and Aristotle

Agamben is committed to showing that the core Foucauldian distinction is purely conceptual — it distinguishes things for us, it makes politics more intelligible, but it does not reflect any concrete historical progression. In a move characteristic of contemporary theorists, Agamben is skeptical not only of Foucault’s distinction reflecting a genuine historical change, but that even the conceptual distinction might function in a more synthetic way.

Agamben goes back to Aristotle — from whom Foucault also drew on — in order to suggest that the apparent distinction between our political life and the rest of our lives (which Agamben sometimes refers to as our “natural lives”) is more complicated than either Foucault or Aristotle acknowledge. Aristotle claims that natural life is divided from politics by the separation of the polis (the political domain) from the household. Yet, as Agamben notes, Aristotle joins together the political and domestic spheres in his claim that the best kind of life necessarily involves participation in the polis.

Agamben was no doubt influenced by Hannah Arendt, who, in The Human Condition, observes that the model for power adopted in the public realm was critically reliant and that which was established in the context of the household.

Biopolitics and the Exception

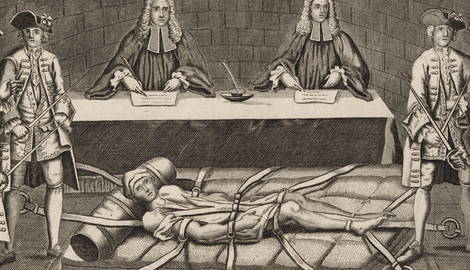

For Agamben, “biopolitics is at least as old as the legal exception.” The legal exception marks the state’s willingness to make judgments about life in general, not merely the political elements of it. Determinations of what constitutes an exception cannot, by their very nature, be captured in the structure of the law as such. Rather, they involve judgments concerning the social order in general. The very possibility of an exception, therefore, admits that the domain of politics ranges over the social world at large.

Agamben follows Carl Schmitt — the political theorist and Nazi jurist — in identifying part of what is distinctive in the state is its capacity to make extra-judicial decisions, and that such decisions are as integral to the construction of the state as the law itself. Indeed, Agamben observes that, far from making the law but an empty pretense, the exception in facts serves to clarify and deepen the rule — it defines the political aspect of the rule. Here, Agamben echoes Carl Schmitt, who claimed that any government which intends to act decisively must contain within itself a “dictatorial” element, which is equivalent to an ability to act in light of exceptions. Schmitt infamously formulated this principle as, “Der Führer schützt das Recht” (The leader defends the law).

Nihilism and Politics

Agamben analyses the distinctive condition of contemporary Western politics not as that which is governed by biopolitical regimes, but rather as that which is characterized by the destruction of experience and nihilism.

The differences between Foucault and Agamben don’t stop there — Foucault is far less concerned with origins than Agamben is, and Agamben is less concerned with historicizing than Foucault is (Agamben locates the origins of the concept of law and life at the very same point). The law is defined only in the exclusion, and the exclusion is all that defines for us what the law includes.

We might think that a fixation on the origins of a concept or a practice tends to bleed into an ideal-conceptual characterization of that thing. Agamben conceives of the sovereign exception not just as outside the law, but as an abandonment by it. To be excluded from the ordinary procedures of the law, to be designated in whatever sense an “abnormal case,” is to be at once submitted to the unlimited force of sovereign power while the sovereign’s responsibility is negated. There is something patently frightening about this picture of state power.

Benjamin and Kafka

With reference to a discussion between Walter Benjamin and Gershom Scholem on the writings of Franz Kafka, Agamben argues that Scholem’s characterization of the state as a “force without significance” captures his (Agamben’s) conception of the state. What constitutes the state are those moments when it acts without any definite, concrete purpose (literally, meaninglessly) and yet still brings all of the force available to it to bear on whoever it chooses.

Agamben partly justifies this view with reference to Benjamin, who was the first to observe that the state of exception effectively conflates the state with life as a whole. Agamben holds that as a natural consequence of this, it is not possible to understand the ends of the state from the position of life outside the state.

Left-wing conceptions of politics tend to oscillate between characterizing the modern, capitalist state as evil or inept: Agamben’s conception of the state appears to reconcile these two conceptions. Perhaps this goes some way to explaining its extraordinary influence today.

Giorgio Agamben on Natural Life, Political Life, and Bare Life

Agamben is sometimes understood as founding political life on natural life. Yet there is a third category of life to consider: “bare life.” This constitutes another of Agamben’s most infamous concepts. Bare life is an intermediary concept — it falls between natural life and our political lives.

Let us clarify again what is at stake in this distinction. Natural life, biological life, whatever we want to call it, is the most private, personal, subjective element of our existence. This might seem curious — isn’t our biological existence impersonal, general, something that everyone possesses? Isn’t subjectivity really about experience, not life as such? In any case, our political lives are less controversially public and interrelated than our natural lives.

This is the distinction bare life appears to complicate. Bare life falls between natural life and political life not in the sense of being part way between the two conceptually, or in the sense of containing elements of each, but rather in the sense that bare life is natural life exposed to the political life. Specifically, it is natural life after it has been politicized by exposing it to the power of death wielded by the state.

Here Agamben returns to Aristotle, and the concepts of zoē (biological life) and bios (political life). While Aristotle’s attempt to distinguish two kinds of life does, as Foucault thought, mean that our biological lives are conceptually separable from our political lives, what does not follow is that our biological lives go untouched by political power. Rather, this distinction creates space for the limit concept, bare life, which is — for Agamben and those who follow him — a conceptual tool for understanding the relationship between our biological existence and the force of the state.