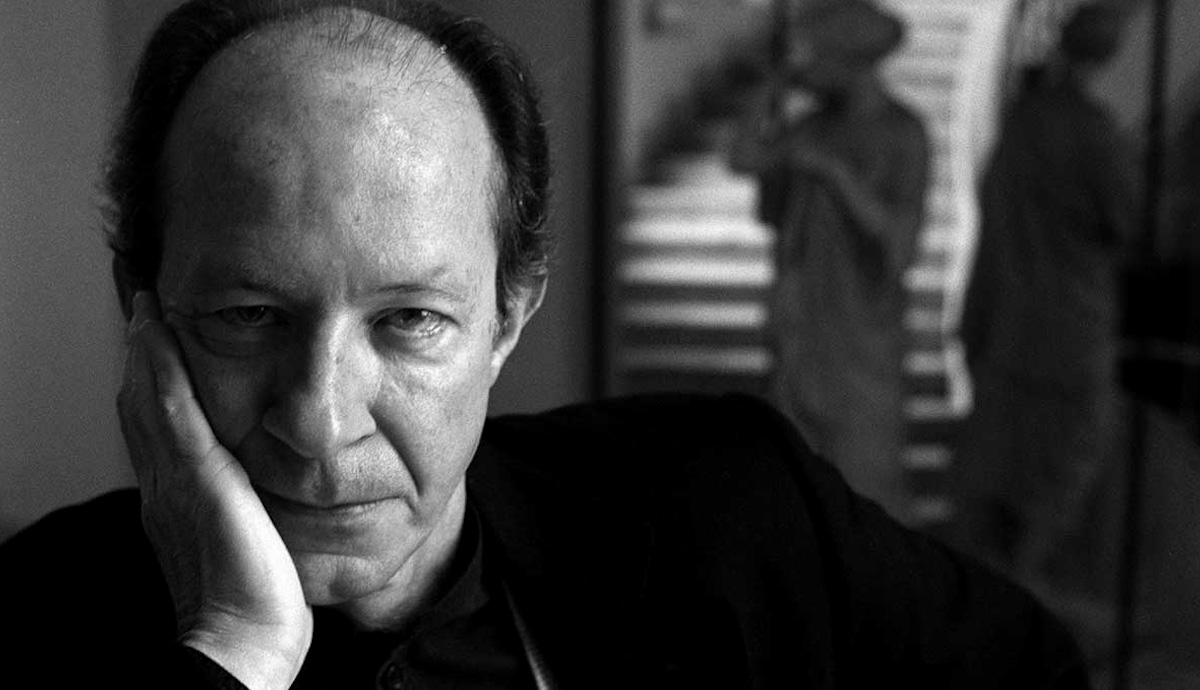

What makes modern life qualitatively different from what came before? By which concepts can we best understand it? Which must we borrow, which must we make? Giorgio Agamben’s authorship represents one of the most comprehensive and intellectually honest attempts to broker a rapport between the sugar-high of contemporary existence and the long cool hour of reflection.

Agamben is an Italian philosopher, literary critic and political theorist. He is one in a succession of European philosophers to have become extremely fashionable in various humanities departments of Anglo-American universities. This can be as much of a blessing as a curse: his work is often reduced to a series of buzzwords and conveniently vacuum-packed critical concepts. This article aims to offer some context for said concepts, and thereby introduce Agamben’s work as a whole.

This article begins with a discussion of Agamben’s philosophy of language, and its relation to his theorization of modernity. It then moves on to address his politics, and several key concepts in his political theory: the state of exception, homo sacer and bare life. It will conclude with a reflection on how Agamben’s work conceives of modernity itself.

Giorgio Agamben on Language and Modernity

The consensus on Agamben’s philosophy as a whole is that he is not a system builder, but that does not mean is his work disordered or inconsistent. It is, perhaps, partly right to say that his work represents an attempt to refine his approaches (not a set of clearly defined stances or principles) to a certain set of philosophical issues. Perhaps first among these is this question: what is language?

Before addressing what Agamben says about language, it is worth saying something about the way he poses the question. In other words, one might wish to ask what Agamben’s style is, and what it says about his approach to language. Why even ask this question in the first place? Questions about the limits of language – what we can express in language, what meaning is and so on – is an almost inextricable part of philosophy of language. Philosophy itself often constitutes an attempt (intentional or otherwise) to stretch the boundaries of meaning and to say what it is difficult to say. The way a philosopher writes and speaks should tell us something about their conception of language as such.

Agamben’s style, in contrast to many Continental ‘theorists’, is terse to the point of under-explanation. Indeed, it is worth dwelling on this term: ‘terse’. Sometimes one becomes aware of the associations which had long been carried by a term after such associations had been guiding one’s use of the term for quite some time. The term ‘terse’ seems inextricably bound to the verb ‘to tear’. One might think they had a similar etymology, given that ‘terse’ is derived from the Latin ‘tergere’, meaning to polish or to clean. Yet tear comes instead from a Germanic route, so whatever ancestry they might share is distant.

Language and Visual Culture

It is difficult for some to conceptualize ‘terse’ language without imagining someone tearing some object or creature apart, ripping at its superfluous, flabby, easily dislodged elements until only the kernel of it remains. Agamben has much to say about this pictorial element of language. His interest in it can, perhaps, be traced to Walter Benjamin, the German writer who was one of Agamben’s most profound influences.

Benjamin was concerned with the replacement of literary culture with visual culture. As he saw it, the visualization of every form of media, the indexing of the written to the visual, was one of the most radical developments of modern life. He develops this theme with the by observing ordinary things with the most extraordinary pathos – observing, for instance, how newspapers which were once arranged horizontally, in order to best accommodate the written prose, are now primarily organized vertically (that is, they are structured by the pictures instead).

Agamben is deeply concerned with the ways in which changes to modern life have structured our relationship to language. He is often characterized as investigating the conditions of speech and language, and about their relationship to metaphysics, or reality in general.

Language, Modern Life and the Impossibility Experience

Often, contemporary life is characterized as an abundance of experience – perhaps an overabundance. The idea that modernity has led to a more stimulating world which we are struggling to negotiate is common to the point of cliché. It is striking, therefore, that Agamben instead characterizes modern life by the impossibility of experience.

Insofar as experience implies any active element, Agamben believes that modern life can only be ‘undergone’. For Agamben, the solution to this new, passive stage of human development lies in language. Experience must be reconstituted in language, not in consciousness, if we are to reinsert the active subject. Agamben wants to develop a philosophy of language which will transform Western metaphysics.

In a certain sense, Agamben’s approach to language expresses a faith in it which goes above and beyond that accorded to it by the philosophical tradition at large. In particular, Agamben calls for us to de-emphasize what is ineffable or unspeakable in language, and return to a state of ‘infancy’ or naivety instead. Perhaps this is why Agamben writes so succinctly: his philosophy presupposes the ability to say everything he needs to say, to say it once; to say it and then stop speaking.

Agamben and Foucault

Many of Agamben’s most famous and influential concepts are political ones. To understand what Agamben has to say about politics, it is necessary to say something about Michel Foucault, whose work he was reacting to and against. Michel Foucault’s conceptual apparatus is as extensive and non-linear as Agamben’s, but a central thought in his work is encapsulated by the following quote:

“For millennia, man remained… a living animal with the additional capacity for a political existence; modern man is an animal whose politics places his existence as a living being in question”.

What form does this increased politicization take? On Foucault’s view, the state used to be concerned with matters of killing and death – its power was instantiated in its potential to kill. What heralds the coming of modernity (and you’ll notice we’re talking again about what makes modernity special) is the state’s intervention into the realm of life – the regulation of the production of life and the way it is lived – “fostering life or disallowing it”. Foucault describes this transition as that between ‘sovereign power’ (pre-modern) and ‘biopower’ (modern).

Agamben’s State of Exception and Homo Sacer

Agamben rejects much of what Foucault has to say. For one thing, Agamben denies the opposition between sovereign and biopolitical forms of power. Rather, “the production of a biopolitical body is the original activity of sovereign power”. What is unprecedented and ‘new’ in modern government is that this production has simultaneously gone into overdrive and gone haywire.

It is at this point we can define one of the most infamous concepts from Agamben’s authorship – the ‘state of exception’. Characteristically, he derives this concept from Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’, in which Benjamin argues that exceptions to the supposed ‘norms’ of the liberal democratic state have themselves become the norm and so now constitute the prevailing state of governance.

Agamben develops this idea further, arguing that the state we are all left in is that which was reserved only for the ‘sacred man’ (homo sacer) under Roman law. The sacred man is defined by his status as an exception – he stands outside both of sacred and profane law, and can be “killed but not sacrificed”.

Giorgio Agamben’s Concept of Bare Life

To better understand the ideas of the ‘state of exception’ and ‘homo sacer’, it is necessary to introduce a final concept from Agamben’s work: that of ‘bare life’. What is bare life? Here, Agamben is developing a distinction one finds in Greek antiquity: that between ‘natural life’ and a particular form of life. The latter form of life – the particular, social, contingent elements of it – is understood to be the proper realm of politics. Conversely, natural life is excluded from political consideration.

The development of sovereign power in the form of ever greater, ever more sophisticated incursions into the realm of biopower, is what is responsible for the creation of bare life. Bare life is natural life that has been politicized. This is why Agamben calls bare life “life exposed to death” – it is natural life which has been subjected to the mortal violence of the state, or the threat of it.

Agamben’s work can be seen as an attempt to grapple with what is distinctive about the times through which he has lived – the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Though this time represents a period of inflection, that Agamben’s greatest influence – Walter Benjamin – developed some of the concepts Agamben borrows and develops in the early 20th century, modernity is presented as more of an intensification of forces than a total break with what came before.